Writing in Word Ways in May 1975, David Silverman noted that the phrase LEFT TURN FROM THIS LANE ONLY, stenciled in the leftmost traffic lane at various U.S. intersections, was ambiguous — and that both meanings had been struck down, in contested court cases in Arizona and California.

In one case, the motorist had driven straight ahead rather than turning, which the prosecutor said was illegal. The motorist returned that this wasn’t so — LEFT TURN FROM THIS LANE ONLY meant that it would be illegal to make a left turn from any other lane, but it didn’t require that a left turn be made from this one. “If the city had meant my failure to turn to be illegal, they should have written FROM THIS LANE, ONLY A LEFT TURN.”

In the other case, the motorist had made a left turn from the lane to the right of one marked LEFT TURN FROM THIS LANE ONLY. He argued that this was legal — the marking required drivers in the leftmost lane to turn left, but imposed no requirement on the other lanes. “Had the city wanted to make my turn illegal the marking should have been LEFT TURN ONLY FROM THIS LANE.”

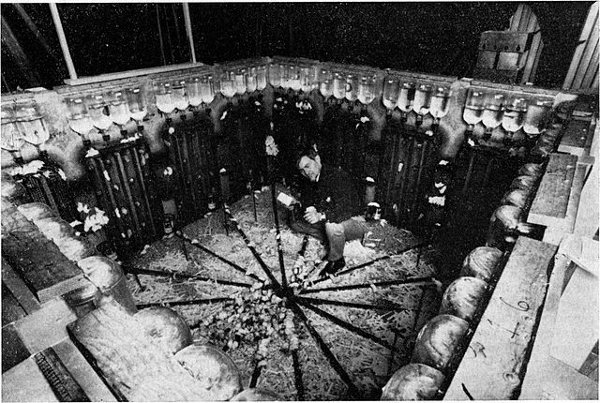

Both motorists were found not guilty. Perhaps because of such confusion, Silverman noted, most intersections had lately begun to use unambiguous arrows: “One good picture is worth ten thousand signs reading LEFT TURN IF AND ONLY IF FROM THIS LANE.”