Multiplication is mie vexation,

And Division is quite as bad,

The Golden Rule is mie stumbling stule,

And Practice drives me mad.

So wrote an anonymous English student in 1570. Matters had not progressed far in 1809, when 6-year-old Marjorie Fleming wrote in her diary: “I am now going to tell you about the horible and wretched plaege my multiplication gives me you cant concieve it — the most Devilish thing is 8 times 8 & 7 times 7 it is what nature itselfe cant endure.”

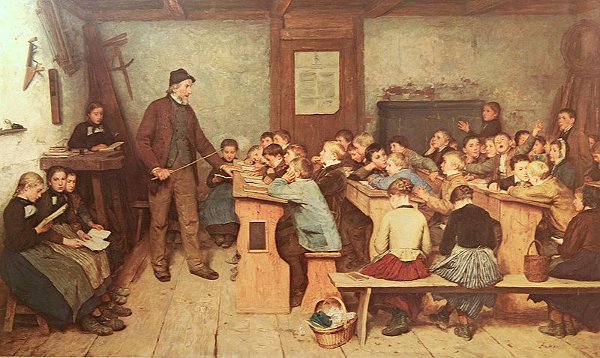

Alas, the feeling is sometimes shared. After serving four years as a teacher, D.H. Lawrence wrote:

When will the bell ring, and end this weariness?

How long have they tugged the leash, and strained apart

My pack of unruly hounds: I cannot start

Them again on a quarry of knowledge they hate to hunt,

I can haul them and urge them no more.

No more can I endure to bear the brunt

Of the books that lie out on the desks: a full three score

Of several insults of blotted pages and scrawl

Of slovenly work that they have offered me.

I am sick, and tired more than any thrall

Upon the woodstacks working weariedly.

And shall I take

The last dear fuel and heap it on my soul

Till I rouse my will like a fire to consume

Their dross of indifference, and burn the scroll

Of their insults in punishment? — I will not!

I will not waste myself to embers for them,

Not all for them shall the fires of my life be hot,

For myself a heap of ashes of weariness, till sleep

Shall have raked the embers clear: I will keep

Some of my strength for myself, for if I should sell

It all for them, I should hate them —

— I will sit and wait for the bell.