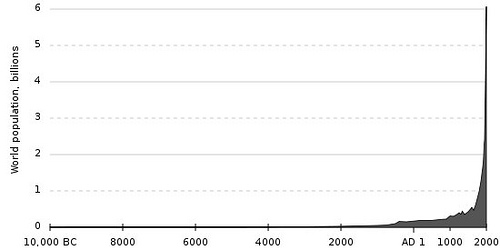

The world population has doubled between:

- 1181 and 1715

- 1715 and 1881

- 1881 and 1960

- 1960 and 1999

It’s expected to reach 9 billion by 2040.

The world population has doubled between:

It’s expected to reach 9 billion by 2040.

Evangelical author Favell Lee Mortimer (1802-1878) set foot only twice outside England, but that didn’t stop her from writing harrowing travel books for Victorian children. From The Countries of Europe Described (1850):

“I do not mean to say that there are as many robbers in Sweden as in Sicily; there the robbers are seldom punished at all: in Sweden they are punished; but yet the rest of the people go on stealing.”

In 2007, prison inmate Charles Jay Wolff sent a hard-boiled egg to U.S. District Court Judge James Muirhead in Concord, N.H.

Wolff, who was awaiting trial for sexual assault, said he was an Orthodox Jew and demanded a kosher diet.

In his judgment, Muirhead wrote:

I do not like eggs in the file.

I do not like them in any style.

I will not take them fried or boiled.

I will not take them poached or broiled.

I will not take them soft or scrambled,

Despite an argument well-rambled.

No fan I am of the egg at hand.

Destroy that egg! Today! Today!

Today I say!

Without delay!

“We’ve told him, if you don’t like the eggs, don’t eat them,” said Assistant Attorney General Andrew Livernois.

It’s said that police sergeants in Leith, Scotland, used this tongue twister as a sobriety test:

The Leith police dismisseth us,

I’m thankful, sir, to say;

The Leith police dismisseth us,

They thought we sought to stay.

The Leith police dismisseth us,

We both sighed sighs apiece;

And the sigh that we sighed as we said goodbye

Was the size of the Leith police.

If you can’t say it, you’re drunk.

Medieval sportsmen invented collective nouns for everything from owls to otters. Less well known are the terms they invented for people — this list is taken from Joseph Strutt, The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England, 1801:

In 1793, two years after publishing his translation of Homer, William Cowper received this letter from 12-year-old Thomas Hayley, pointing out its defects:

HONORED KING OF BARDS,–Since you deign to demand the observations of an humble and unexperienced servant of yours, on a work of one who is so much his superior (as he is ever ready to serve you with all his might) behold what you demand! but let me desire you not to censure me for my unskilful and perhaps (as they will undoubtedly appear to you) ridiculous observations; but be so kind as to receive them as a mark of respectful affection from your obedient servant,

THOMAS HAYLEY

Book I, Line 184. I cannot reconcile myself to these expressions, ‘Ah, cloth’d with impudence, etc.’; and 195, ‘Shameless wolf’; and 126, ‘Face of flint.’

Book I, Line 508. ‘Dishonor’d foul,’ is, in my opinion, an uncleanly expression.

Book I, Line 651. ‘Reel’d,’ I think makes it appear as if Olympus was drunk.

Book I, Line 749. ‘Kindler of the fires in Heaven,’ I think makes Jupiter appear too much like a lamplighter.

Book II, Lines 317-319. These lines are, in my opinion, below the elevated genius of Mr. Cowper.

Book XVIII, Lines 300-304. This appears to me to be rather Irish, since in line 300 you say, ‘No one sat,’ and in 304, ‘Polydamas rose.’

Cowper wrote back, “A fig for all critics but you!”

Most Exalted Sir,–

It is with most habitually devout expressions of my sensitive respect that I approach the clemency of your masterful position with the self-dispraising utterance of my esteem, and the also forgotten-by-myself assurance that in my own mind I shall be freed from the assumption that I am asking unpardonable donations if I assert that I desire a short respite from my exertions; indeed, a fortnight’s holiday, as I am suffering from three boils, as per margin. I have the honorable delight of subscribing myself your exalted reverence’s servitor.

– Jonabol Panjamjaub

– An Indian clerk’s request for a holiday, quoted in William Shepard Walsh, Handy-Book of Literary Curiosities, 1892

“In addition to the regalement of the ear from the charm of style to his communication, the eye is gratified by a rough but graphic illustration of the three boils.”

In 1996, 21-year-old John Leonard saw a Pepsi ad that jokingly offered a Harrier fighter for 7 million “Pepsi points.” Under the contest rules, that should have required drinking 16.8 million cans of Pepsi, but Leonard found a loophole — he could earn the points by simply buying them for 10 cents each.

So on March 28 he delivered 15 original Pepsi points, plus a check for $700,008.50 to cover the remainder plus shipping and handling. And when Pepsi failed to deliver the jet, he sued.

He lost in the end — the court ruled that the ad didn’t constitute an offer — but Leonard can still argue that he was in the right. He claimed that a federal judge could not hear his case fairly, and that instead he should have faced a jury of “the Pepsi generation.”

(Thanks, Brendan.)

William Gladstone once asked Michael Faraday the practical value of electricity.

“Why, sir,” the physicist replied, “presently you will be able to tax it.”

If this should meet the eye of Emma D—–, who absented herself last Wednesday from her father’s house, she is implored to return, when she will be received with undiminished affection by her almost heart-broken parents. If nothing can persuade her to listen to their joint appeal–should she be determined to bring their gray hairs with sorrow to the grave–should she never mean to revisit a home where she had passed so many happy years–it is at least expected, if she be not totally lost to all sense of propriety, that she will, without a moment’s further delay, send back the key of the tea-caddy.

– Advertisement, London newspaper, quoted in Jefferson Saunders, The Tin Trumpet, 1836