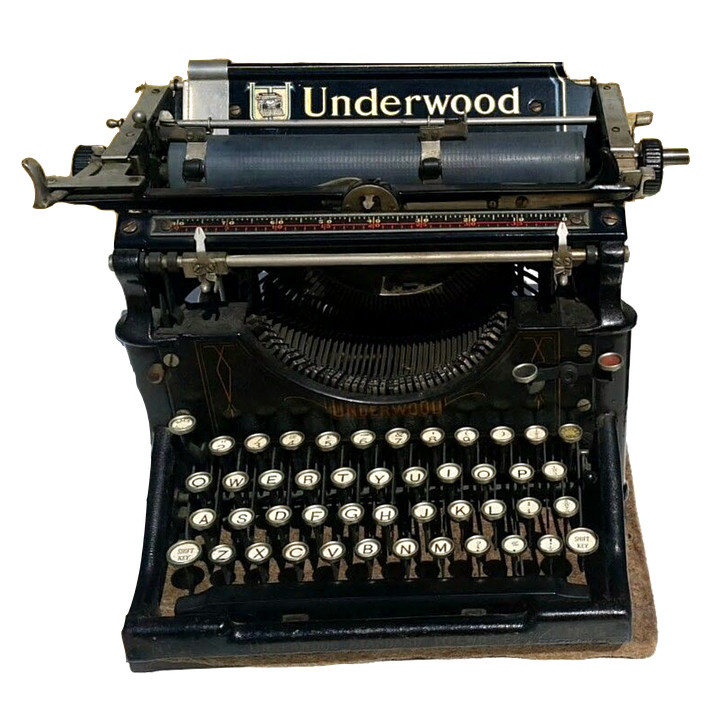

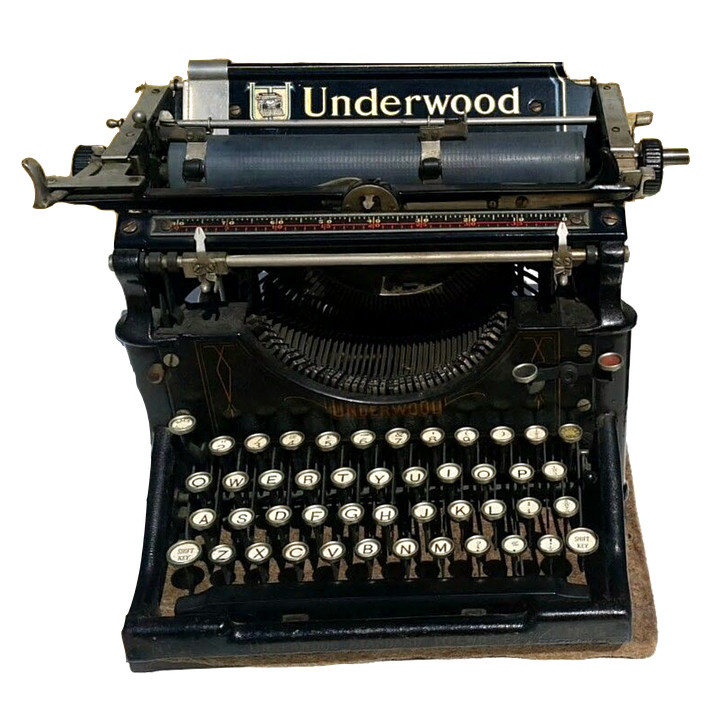

It’s sometimes suggested that the modern QWERTY keyboard was designed so that typewriter salesmen could impress customers by typing the phrase TYPEWRITER QUOTE on the top row of keys.

It wasn’t, but they could.

It’s sometimes suggested that the modern QWERTY keyboard was designed so that typewriter salesmen could impress customers by typing the phrase TYPEWRITER QUOTE on the top row of keys.

It wasn’t, but they could.

A writer in The Builder has cleverly suggested that bridges might be erected in the crowded thoroughfares of London for the convenience of foot passengers, who lose so much valuable time in crossing. As the stairs would occupy a considerable space, and occasion much fatigue, I beg to propose an amendment: Might not the ascending pedestrians be raised up by the descending? The bridge would then resemble the letter H, and occupy but little room. Three or four at a time, stepping into an iron framework, would be gently elevated, walk across, and perform by their weight the same friendly office for others rising on the opposite side. Surely no obstacles can arise which might not be surmounted by ingenuity. If a temporary bridge were erected in one of the parks the experiment might be tried at little cost, and, at any rate, some amusement would be afforded. C.T.

— Notes and Queries, July 17, 1852

In 1907, two boys in Alameda, Calif., used homemade wireless sets to intercept messages sent from Navy ships to “boudoirs ashore”:

Miss Brown, Oakland — Can’t meet you to-night. No shore leave. Be good in the meantime.

Mrs. Blank, Alameda — Will see you sure to-morrow night. Didn’t like to take too many chances yesterday. We must be discreet.

[from an officer to a woman on Mare Island:] Honestly, could not show last night. Am arranging so I can see you oftener. Will take you to dinner Wednesday afternoon.

A married woman on Mare Island wrote to another woman’s husband, an officer, “All lovely. I’m sure you are mistaken. Call again. Your P.L.”

“Debutantes, it appears, use the wireless system of the navy to relieve their irksome task of correspondence, for there are many fond messages in the book from evidently ingenuous girls to midshipmen and other young officers,” reported the San Francisco Examiner. “At least a third of the messages belong to the class that can not be regarded in any light but confidential without inverting all accepted canons of discretion.”

For a 1929 airport design competition, H. Altvater of New York proposed a huge wheel of interlocking runways set atop a ring of skyscrapers.

The judges ruled it “beyond the expressed purpose of the competition” but noted that “it is quite possible that in the future some of the features considered objectionable today will prove entirely practical.”

Michael Snow’s 1967 experimental film Wavelength consists essentially of an extraordinarily slow 45-minute zoom on a photograph on the wall of a room. William C. Wees of McGill University points out that this raises a philosophical question: What visual event does this zoom create? In a tracking shot, the camera moves physically forward, and its viewpoint changes as a person’s would as she advanced toward the photo. In Wavelength (or any zoom) the camera doesn’t move, and yet something is taking place, something with no analogue in ordinary experience.

“If I actually walk toward a photograph pinned on a wall, I find that the photograph does, indeed, get larger in my visual field, and that things around it slip out of view at the peripheries of my vision. The zoom produces equivalent effects, hence the tendency to describe it as ‘moving forward.’ But I am really imitating a tracking shot, not a zoom. … I think it is safe to say that no perceptual experience in the every-day world can prepare us for the kind of vision produced by the zoom.”

“What, in a word, happens during a viewing of that forty-five minute zoom? And what does it mean?”

(From Nick Hall, The Zoom: Drama at the Touch of a Lever, 2018.)

World War I’s final ceasefire went into effect at a precise moment: 11:00 a.m. Paris time on Nov. 11, 1918. The French had worked out a way of recording sound signals on film — they used it to infer the position of enemy guns by determining the time between the sound of a shell’s firing and its explosion. This gives us a visual record of the end of the fighting, six representative seconds from the periods before and after the armistice. (Note, though, that the minute immediately before and the one immediately after the ceasefire aren’t shown, “to emphasize the contrast.”)

I don’t have an original source for this — Time magazine credits the U.S. Army Signal Corps.

Possibly useful:

You can ask Google to flip a coin for you.

Also, typing d4, d6, d8, d10, d12, or d20 will roll a die. (Or just search for “dice roller”.)

You can add dice, or declare a constant to be added to the total, using the icons at the bottom.

Also: calculator, metronome, color picker, spinner (including a virtual fidget), breathing exercise for meditation.

It is not every maiden, in these prosaic days, who can summon the ‘tell-tale blood’ to her cheeks at will, or silently reveal by an opportune roseate flush, those inward feelings to which many young ladies experience such difficulty in giving verbal expression. But as the value of the blush, as a highly effective weapon in the feminine armory, is still universally recognized by the sex, although it would appear to have somewhat fallen into desuetude, French ingenuity has been at the pains of devising a mechanical appliance for the instantaneous production of a fine natural glow upon the cheek of beauty, no matter how constitutionally lymphatic or philosophically unemotional its proprietress may be. This thoughtful contrivance is called ‘The Ladies’ Blushing Bonnet,’ to the side ribbons of which — those usually tied under the fair wearer’s chin — are attached two tiny but powerful steel springs, ending in round pads, which are brought to bear upon the temporal arteries by the action of bowing the head, one exquisitely appropriate to modest embarrassment, and by artificially forcing blood into the cheeks cause them to be suffused with ‘the crimson hue of shame’ at a moment’s notice. Should these ingenious head coverings become the fashion among girls of the period, it will behoove ‘young men about to marry’ to take a sly peep behind the bonnet-strings of their blushing charmers immediately after proposing, in order to satisfy themselves that the heightened color, by them interpreted as an involuntary admission of reciprocated affection, is not due to the agency of a carefully adjusted ‘blushing bonnet.’

— London Telegraph, via Robinson [Ill.] Constitution, Dec. 1, 1880

A pathetic incident in connection with a biograph scene occurred in Detroit, Mich., March 17th last. A view made at the occupation of Peking was being flashed across the screen. It represented a detachment of the Fourteenth United States Infantry entering the gates of the Chinese Capital. As the last file of soldiers seemed literally stepping out of the frame on to the stage, there arose a scream from a woman who sat in front.

‘My God!’ she cried hysterically, ‘there is my dead brother Allen marching with the soldiers.’

The figure had been recognized by others in the audience as that of Allen McCaskill, who had mysteriously disappeared some years before. Subsequently Mrs. Booth, the sister, wrote to the War Department and learned that it really was her brother whose presentment she so strangely had been confronted with.

— “Photography,” Popular Science News, October 1901

When London’s Millennium Bridge opened in 2000, it began to sway unexpectedly under the footsteps of the inaugural crowds. The danger of vibration in bridges was well known — the Albert Bridge (below) still bears a sign dating from 1873 that warns soldiers to break step while crossing. But the Millennium Bridge revealed a new phenomenon: As the pedestrians felt the bridge swing beneath them, they altered their movements to maintain their balance and began to sway together in step. This increased the amplitude of the bridge’s oscillations, a factor called synchronous lateral excitation.

The bridge was closed on opening day and underwent $9 million in repairs to increase its damping. It reopened in February 2002 and is now free of vibration, but it’s still known affectionately as the “wobbly bridge.”