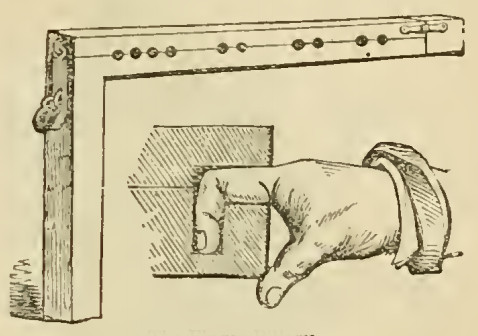

Here’s a forgotten punishment. In the 17th century, in return for a minor offense such as not attending to a sermon, a wrongdoer might be required to place his finger into an L-shaped hole over which a block was fastened to keep the knuckle bent. “[T]he finger was confined, and it will easily be seen that it could not be withdrawn until the pillory was opened,” writes William Andrews in Medieval Punishments (1898). “If the offender were held long in this posture, the punishment must have been extremely painful.”

In his 1686 history of Staffordshire, Robert Plot recalls a “finger-Stocks” “made for punishment of the disorders, that sometimes attend feasting at Christmas time.” Into this “the Lord of misrule, used formerly to put the fingers of all such persons as committed misdemeanors, or broke such rules, as by consent were agreed on for the time of keeping Christmas, among servants and others of promiscuous quality.”