This must have scared the daylights out of people in 1895 — The Execution of Mary Stuart, one of the first films to use editing for special effects.

After the executioner raises his ax, the actress is replaced with a mannequin.

This must have scared the daylights out of people in 1895 — The Execution of Mary Stuart, one of the first films to use editing for special effects.

After the executioner raises his ax, the actress is replaced with a mannequin.

In 1878 Coney Island mounted electric lights on poles so that visitors could play in the surf at night.

“One could take many a long journey and never meet elsewhere with so strange, so truly weird a sight as this,” reported Scribner’s Monthly. “The concentrated illumination falls on the formidable breakers plunging in against the foot of the bridge, and gives them spots of sickly green translucence below and sheets of dazzlingly white foam above. There is a startling spot of foreground and nothing more. A couple who are confident swimmers, possibly a man and his wife, come down the bridge and put off into the cold flood. The woman holds by the man’s belt behind, and he disappears with her into the darkness. A circle disports with hobgoblin glee around a kind of May-pole in the water.”

“Nothing else,” opined the New York Times, “would answer the purpose of those lunatics who persist in bathing after nightfall.”

Last year I mentioned Sullivan & Considine’s Theatrical Cipher Code of 1905, a telegraphic code for “everyone connected in any way with the theatrical business.” The idea is that performers, managers, and exhibitors could save money on telegrams by replacing common phrases with short code words:

Filacer – An opera company

Filament – Are they willing to appear in tights

Filander – Are you willing to appear in tights

Filiation – Chorus girls who are shapely and good looking

Filibuster – Chorus girls who are shapely, good looking, and can sing

At the time I lamented that I had only one page. Well, a reader just sent me the whole book, and it is glorious:

Abbacom – Carry elaborate scenery and beautiful costumes

Abbalot – Fairly bristles with hits

Abditarum – This attraction will hurt our business

Addice – Why have not reported for rehearsal

Admorsal – If you do not admit at once will have to bring suit of attachment

Behag – Not the fault of play or people

Bordaglia – Do not advance him any money

Boskop – Understand our agent is drinking; if this is true wire at once

Bosom – Understand you are drinking

Bosphorum – Understand you are drinking and not capable to transact business

Bosser – We are up against it here

Bottle – You must sober up

Bouback – Your press notices are poor

Deskwork – A versatile and thoroughly experienced actress

Despair – Absolute sobriety at all times essential

Detour – Actress for emotional leads

Devilry – Actress with child preferred

Dextral – An actor with fine reputation and proven cleverness

Dishful – Comedian, Swedish dialect

Disorb – Do not want drunkards

Dispassion – Do you object to going on road

Distal – Good dresser(s) both on and off stage

Dormillon – Lady for piano

Drastic – Must be shapely and good looking

Druism – Not afraid of work

Eden – Strong heavy man

Election – What are their complexions

Epic – Does he impress you as being reliable and a hustler

Exclaimer – Are they bright, clever and healthy children

Eyestone – Can you recommend him as an experienced and competent electrician

Faro – A B♭ cornetist

Flippant – Must understand calcium lights

Fluid – Is right up-to-date and understands his business from A to Z

Forester – Acts that are not first class and as represented, will be closed after first performance

Foxhunt – Can deliver the goods

Gultab – The people will not stand for such high prices

Hilbert – State the very lowest salary for which she will work, by return wire

Jansenist – Fireproof theatre

Jinglers – How did the weather affect house

Jolly – Temperature is 15° above zero

There’s also an appendix for the vaudeville circuit:

Kajuit – Trick cottage

Kakour – Grotesque acrobats

Kalekut – Sparring and bag punching act

Kernwort – Troupe of dogs, cats and monkeys

Kluefock – Upside down cartoonist

Koegras – Imitator of birds, etc.

Letabor – Act is poorly staged and arranged

Litterat – The asbestos curtain has not arrived yet

Mallius – How many chairs do you need in the balcony

Meleto – Is the opposition putting on stronger shows than we

The single word “Lechuzo” stands for “Make special effort to mail your report on acts Monday night so as to enable us to determine your opinion of the same, as in many instances yours will be the first house that said act has performed in, and again by receiving your report early it enables us to correct in time any error that may be made regarding performer, salary and efficiency.”

(Thanks, Peter.)

Cycling is popular in Trondheim, Norway, but the 130-meter hill Brubakken is more than some riders can manage. So the city installed the world’s first bicycle lift — press the start button and a plate will appear under your right foot and push you up the hill at 3-4 mph, rather like a ski lift.

With a maximum capacity of 6 cyclists per minute, the system has pushed more than 200,000 cyclists to the top of the hill in its 15 years of operation.

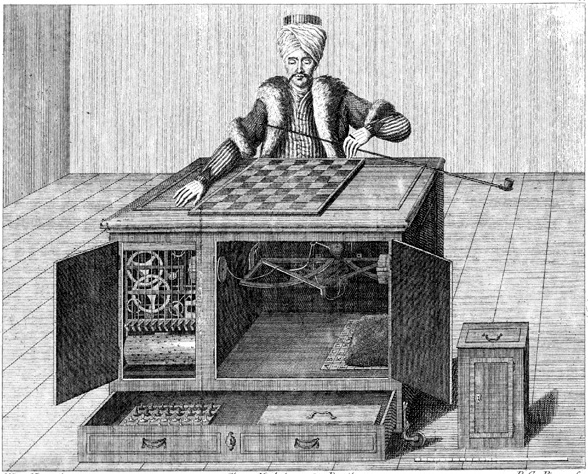

In 1770, Hungarian engineer Wolfgang von Kempelen unveiled a miracle: a mechanical man who could play chess against human challengers. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll meet Kempelen’s Mechanical Turk, which mystified audiences in Europe and the United States for more than 60 years.

We’ll also sit down with Paul Erdős and puzzle over a useful amateur.

In 1973, at the Cricketers Arms pub in Wisborough Green, West Sussex, Irishman Jim Gavin was bemoaning the high cost of motorsports when he noticed that each of his friends had a lawnmower in his garden shed. He proposed a race in a local field and 80 competitors turned up.

That was the start of the British Lawn Mower Racing Association, “the cheapest motorsport in the U.K.” — the guiding principles are no sponsorship, no commercialism, no cash prizes, and no modifying of engines. (The mower blades are removed for safety.) The racing season runs from May through October, with a world championship, a British Grand Prix, an endurance championship, and a 12-hour endurance race, and all profits go to charity.

For the past 26 years, Bertie’s Inn in Reading, Pa., has held a belt sander race (below) in which entrants ride hand-held belt sanders along a 40-foot-long plywood track. All entry fees and concession sales are donated to the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

Each competitor keeps one hand on the sander’s front knob and the other on the rear power switch while an assistant runs behind, paying out an extension cord. Women tend to excel, apparently because they can balance better than men. “You can’t lean back or lean forward,” Donna Knight, who won her heat in 2013, told the Reading Eagle.

Anne Thomas, who owns the inn with her husband, Peter, said, “We must be crazy, but everybody loves it and has a great time, and we raise a lot of money for charity. We tried to quit one time, and nobody would let us.”

During the London Gin Craze of the early 18th century, when the British government started running sting operations on petty gin sellers, someone invented a device called the “Puss-and-Mew” so that the buyer couldn’t identify the seller in court:

The old Observation, that the English, though no great Inventors themselves, are the best Improvers of other Peoples Inventions, is verified by a fresh Example, in the Parish of St. Giles’s in the Fields, and in other Parts of the Town; where several Shopkeepers, Dealers in Spirituous Liquors, observing the Wonders perform’d by the Figures of the Druggist and the Blackmoor pouring out Wine, have turn’d them to their own great Profit. The Way is this, the Buyer comes into the Entry and cries Puss, and is immediately answer’d by a Voice from within, Mew. A Drawer is then thrust out, into which the Buyer puts his Money, which when drawn back, is soon after thrust out again, with the Quantity of Gin requir’d; the Matter of this new Improvement in Mechanicks, remaining all the while unseen; whereby all Informations are defeated, and the Penalty of the Gin Act evaded.

This is sometimes called the first vending machine.

(From Read’s Weekly Journal, Feb. 18, 1738. Thanks, Nick.)

In the 19th century, photographic subjects had to hold still during an exposure of 30 seconds or more. That’s hard enough for an adult, but it’s practically impossible for an infant. So mothers would sometimes hide in the scene, impersonating a chair or a pair of curtains, in order to hold the baby still while the photographer did his work:

More in this Flickr group.

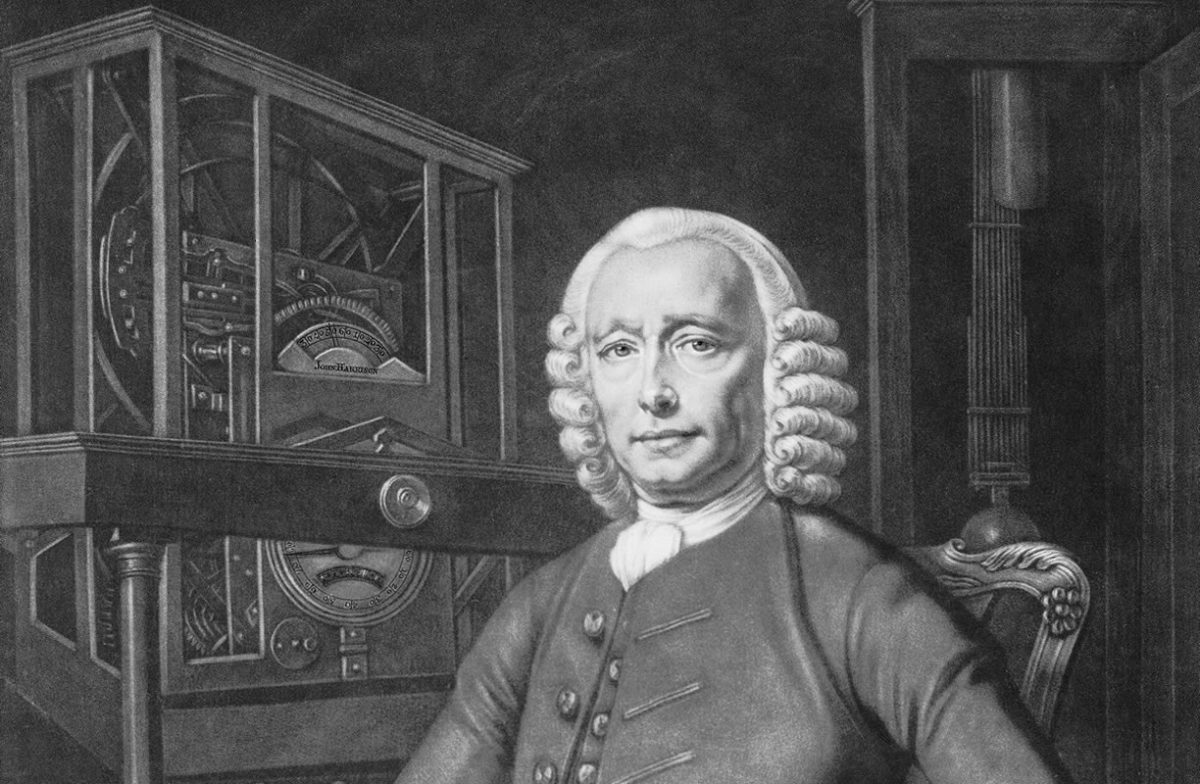

Ships need a reliable way to know their exact location at sea — and for centuries, the lack of a dependable method caused shipwrecks and economic havoc for every seafaring nation. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll meet John Harrison, the self-taught English clockmaker who dedicated his life to crafting a reliable solution to this crucial problem.

We’ll also admire a dentist and puzzle over a magic bus stop.

From an advice column in Home Companion, March 4, 1899:

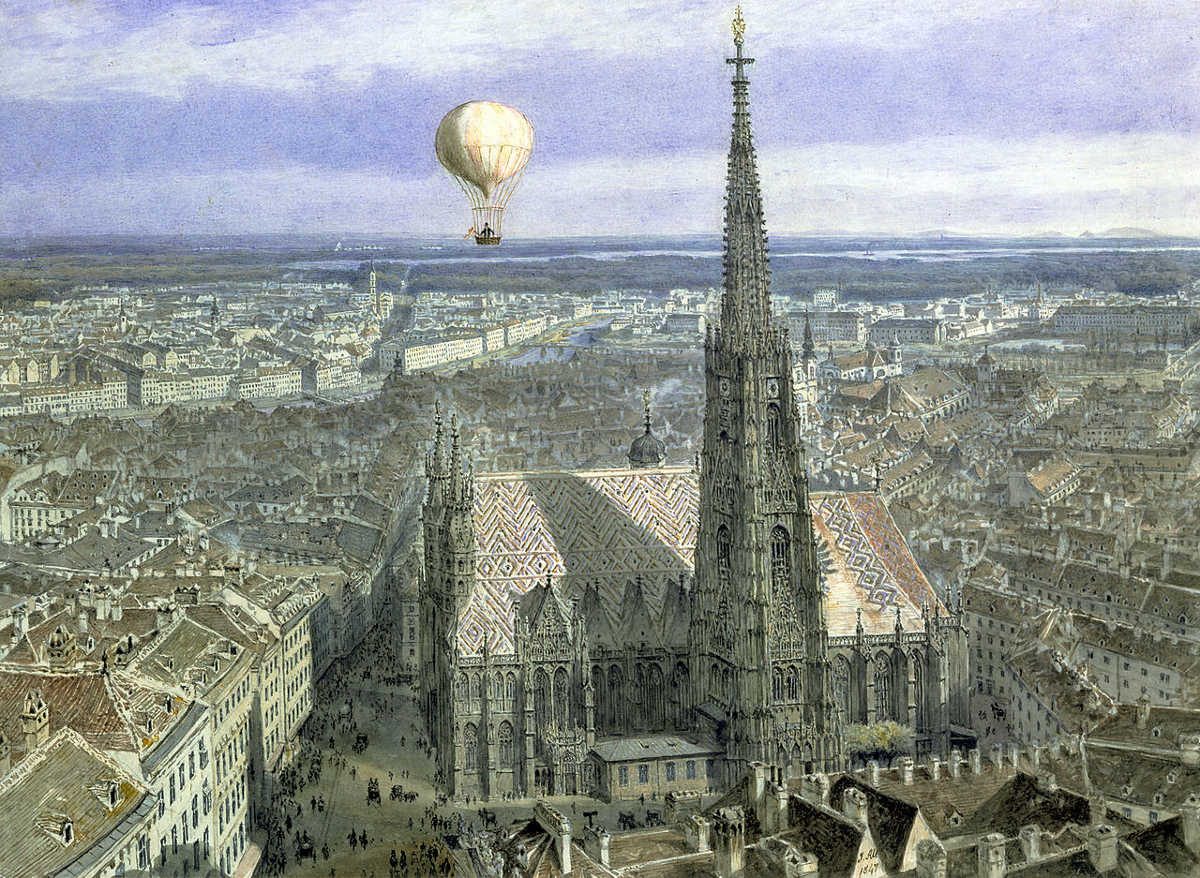

‘Sweet Briar’ (Swansea) writes in great trouble because her lover will persist in his intention to go up in a balloon. She urges him not to imperil his life in this foolhardy manner, but he only laughs at her fears.

I am sorry, ‘Sweet Briar’, that your lover occasions you anxiety in this manner, and I can only hope that he will ultimately see the wisdom of yielding to your wishes. What a pity it is that we have not a law like that which exists in Vienna! There no married man is allowed to go up in a balloon without the formal consent of his wife and children.

One solution: Go up with him, and marry him there.