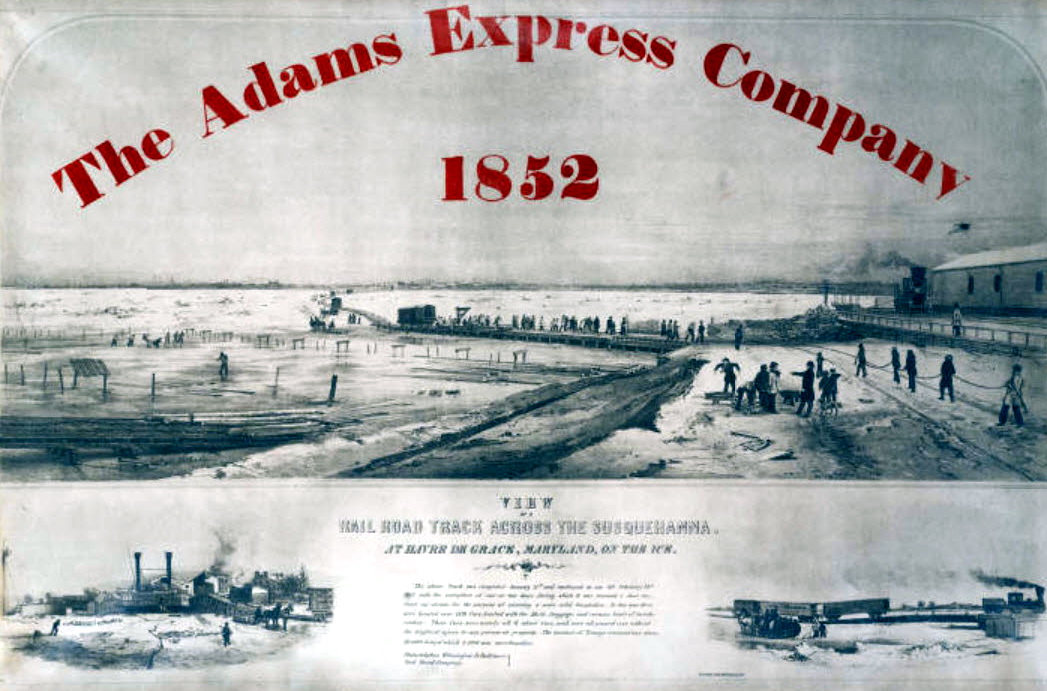

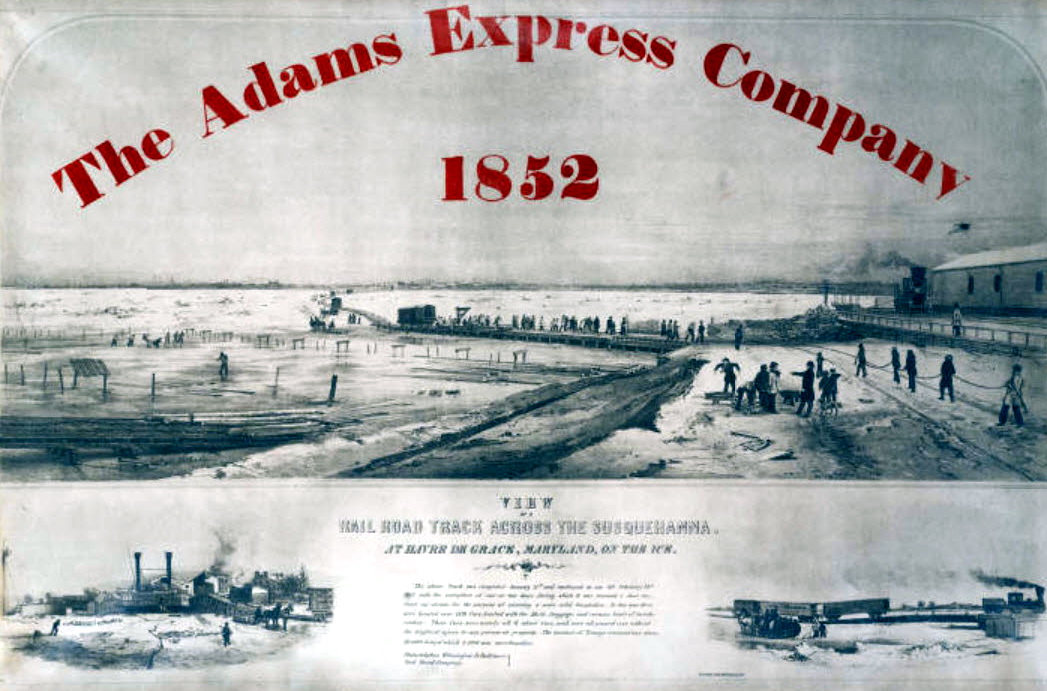

In the 1850s, railroad passengers traveling from Baltimore to Philadelphia would debark at the Susquehanna River, cross the river on a ferryboat, and board a train waiting on the other side. In the severe winter of 1852, so much floating ice had piled up at this point that the ferry couldn’t be used, so railroad engineer Isaac R. Trimble came up with a novel solution: He built a railway across the ice for the baggage and freight cars, and a sledge road beside it along which horses could draw his passengers. The cars had to descend 10 to 15 feet from the bank to the surface of the ice, and at the other side they were tied to a locomotive and pulled up. The “ice bridge” opened on Jan. 15 and was accounted a great success. The Franklin Journal reported, “Forty freight cars per day, laden with valuable merchandise, have been worked over this novel tract by the means above referred to, and were propelled across the ice portion by two-horse sleds running upon the sledge road, and drawing the cars by a lateral towing line, of the size of a man’s finger.”

“At the present writing, this novel and effectual means of maintaining the communication at Havre de Grace is still in successful operation, and will so continue until the ice in the river is about to break up. Then, by means of the sledges, the rails (the only valuable part of the track), can be rapidly moved off by horse power, not probably requiring more than a few hours’ time, so that the communication may be maintained successfully until the last moment. If properly timed, as it doubtless will be, the railroad may be removed, the ice may run out, and the ferry be resumed, it may be, in less than forty-eight hours.”

In fact, wrote historian Charles P. Dare, the ice bridge operated until Feb. 24, “when it was taken up, and, in a few days, the river was free of ice. During this time, 1378 cars loaded with mails, baggage and freight were transported upon this natural bridge, the tonnage amounting to about 10,000 tons. The whole was accomplished without accident of any kind; and the materials were all removed prior to the breaking up of the river without the loss of a cross-tie or bar of iron.”