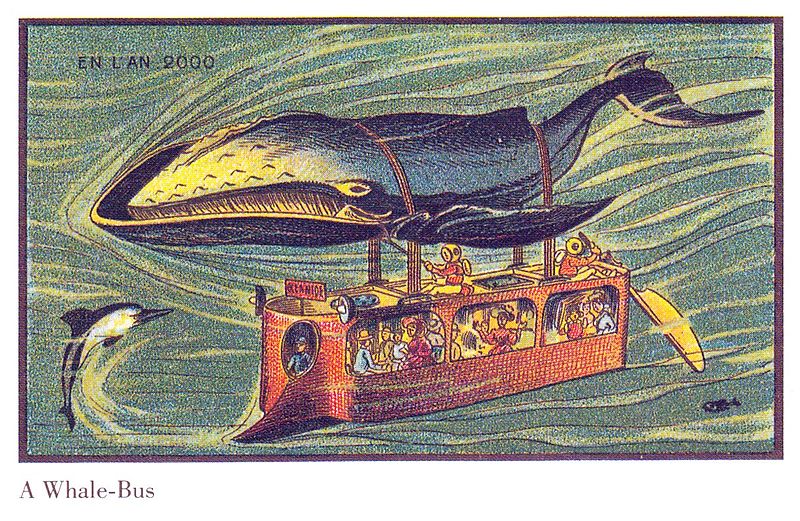

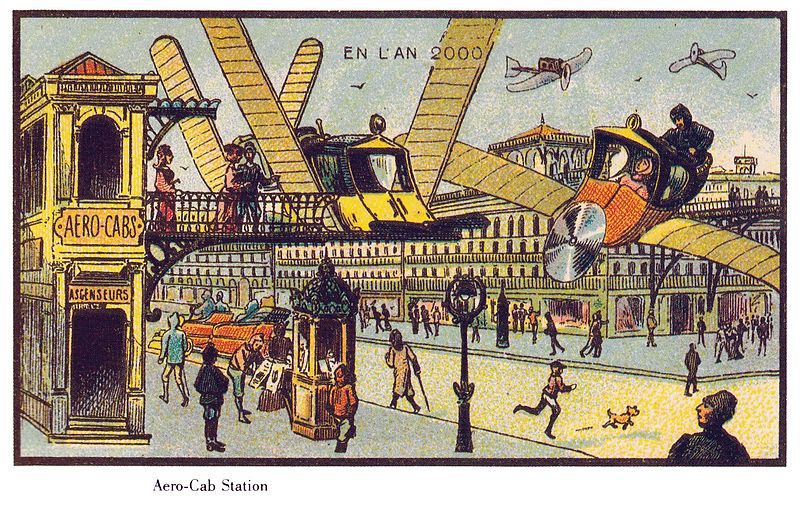

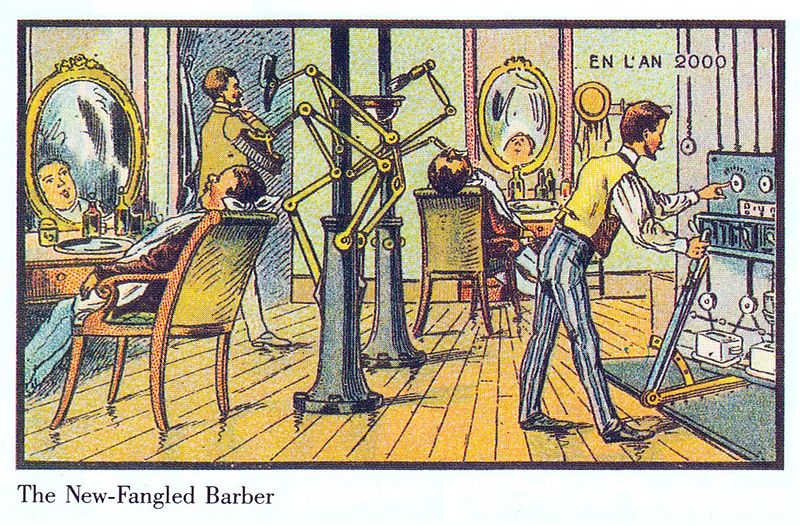

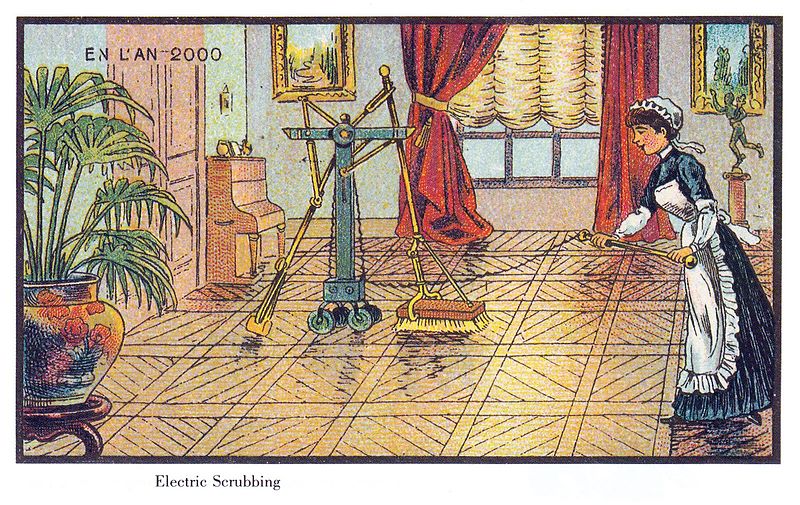

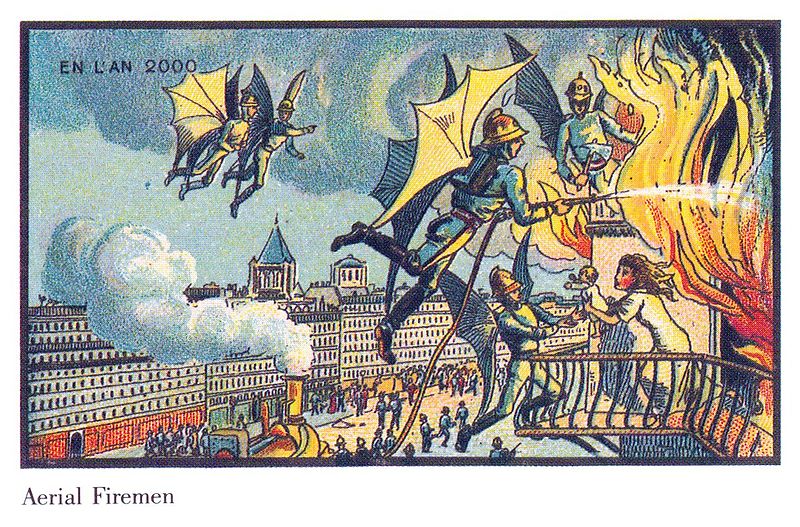

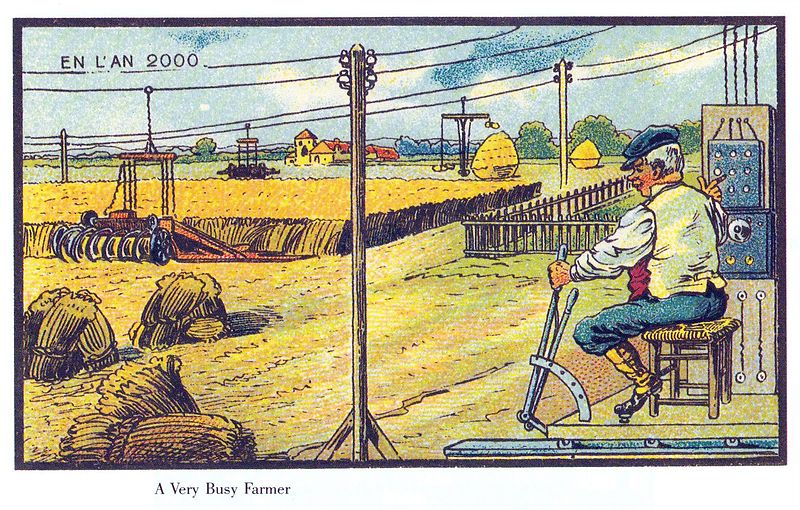

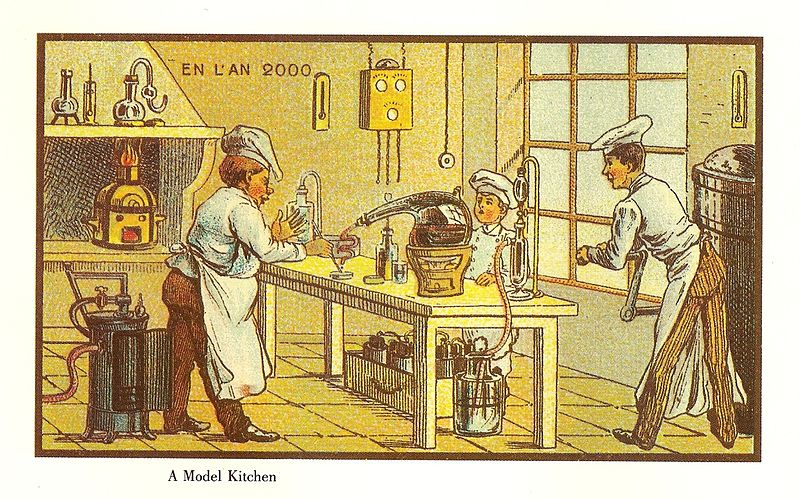

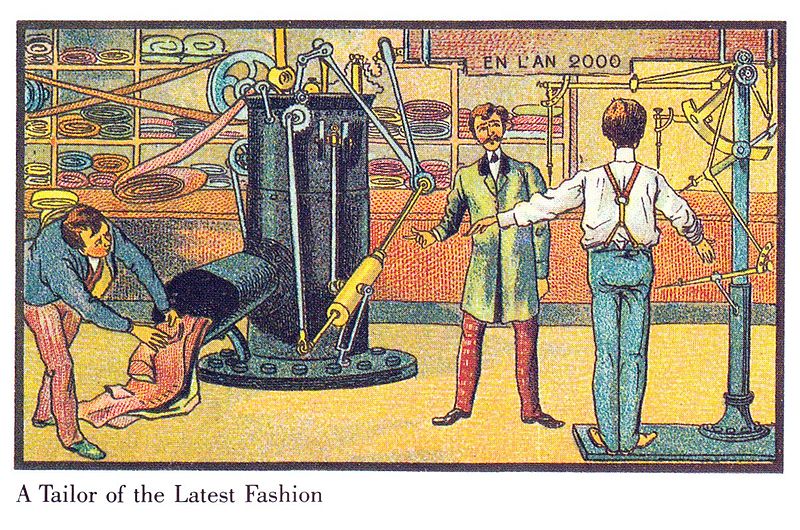

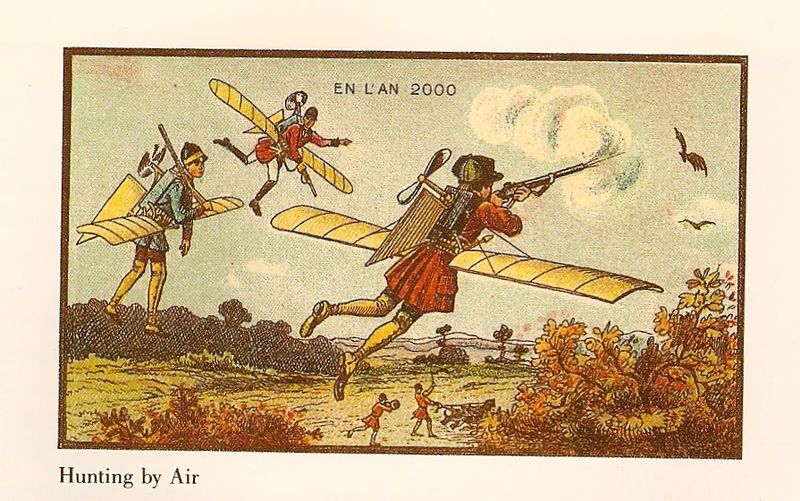

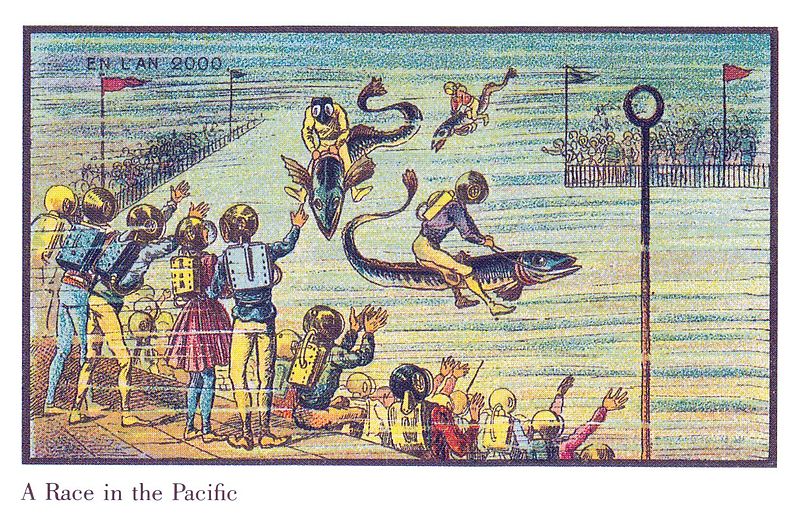

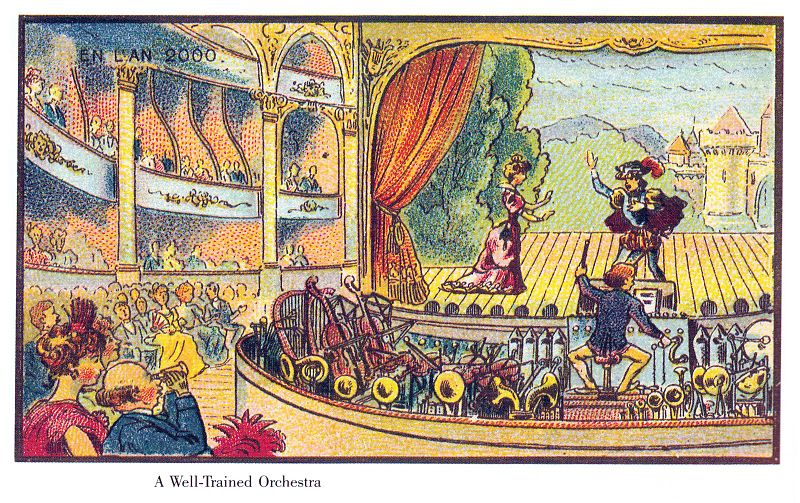

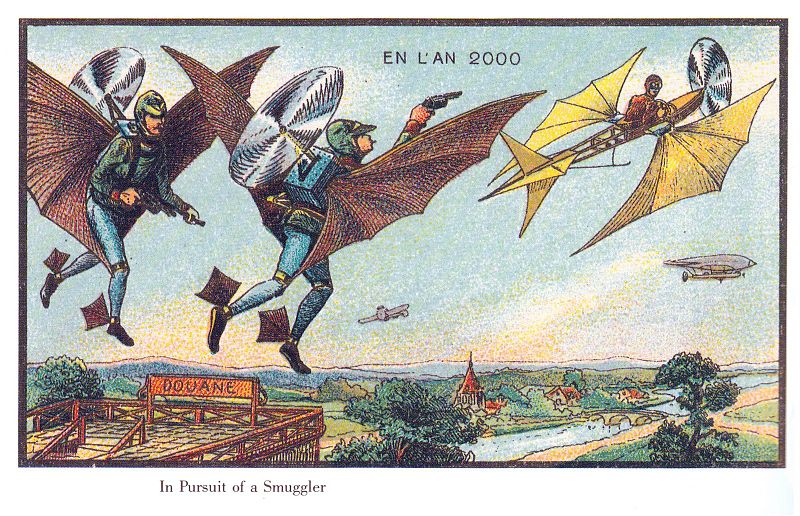

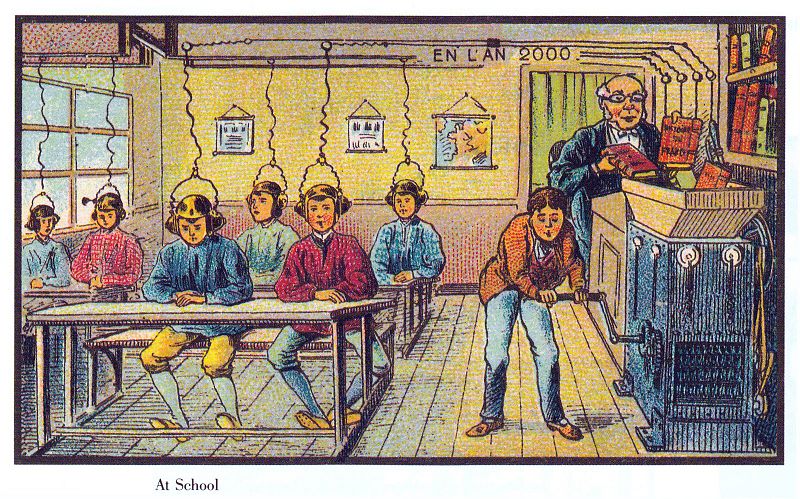

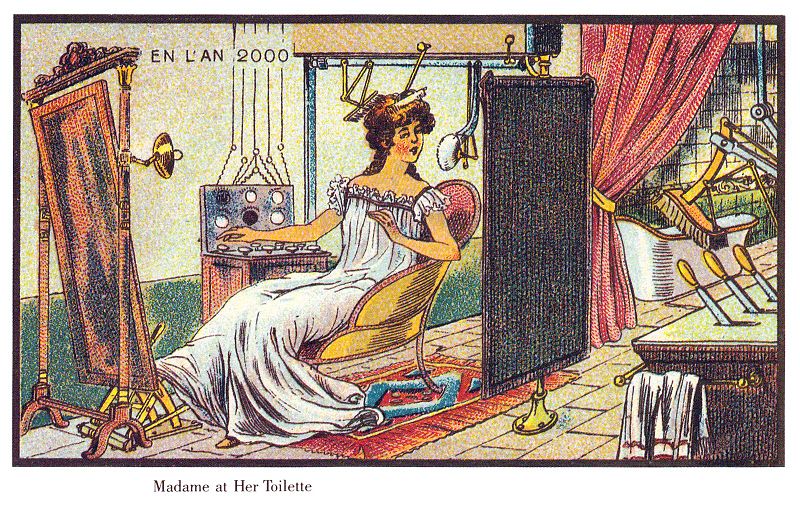

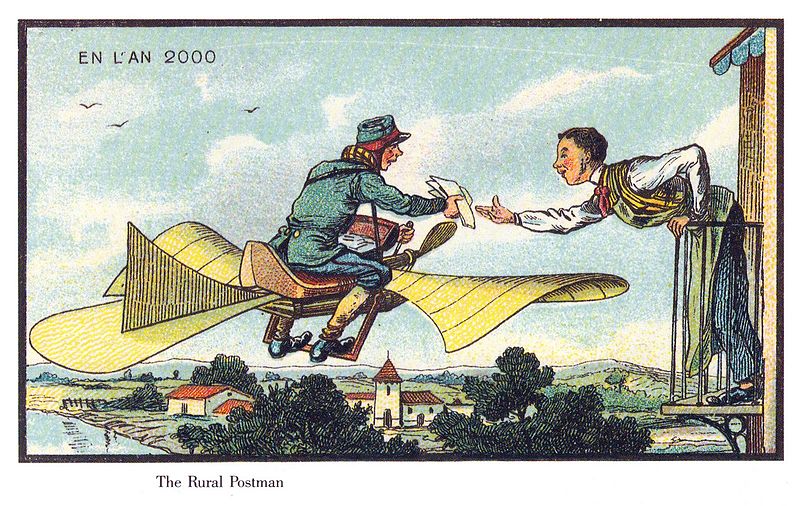

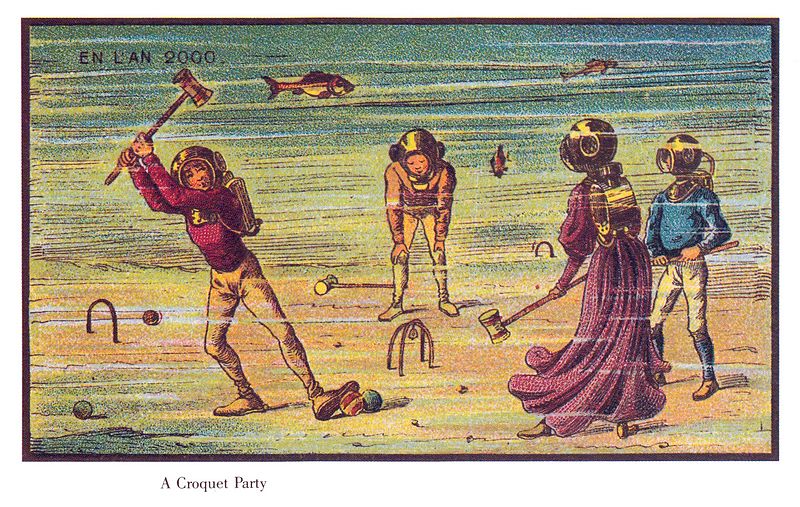

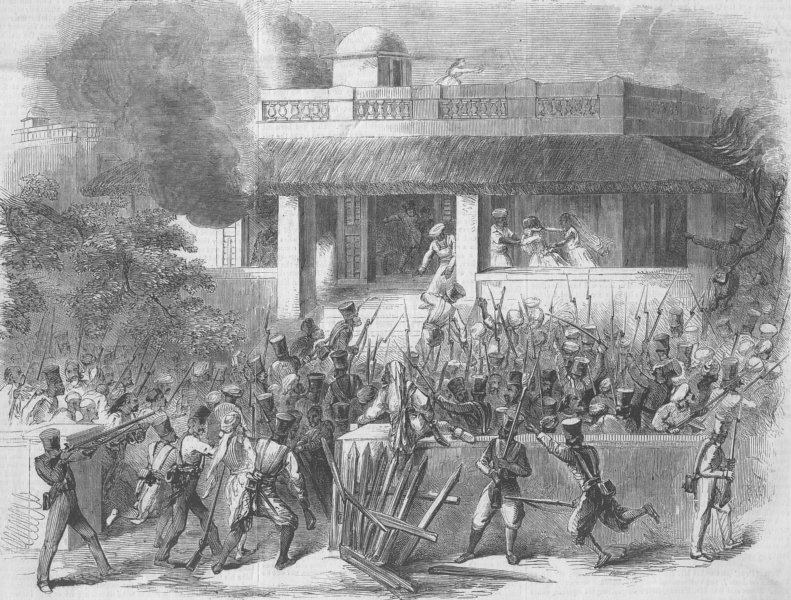

In 1899, preparing for festivities in Lyon marking the new century, French toy manufacturer Armand Gervais commissioned a set of 50 color engravings from freelance artist Jean-Marc Côté depicting the world as it might exist in the year 2000.

The set itself has a precarious history. Gervais died suddenly in 1899, when only a few sets had been run off the press in his basement. “The factory was shuttered, and the contents of that basement remained hidden for the next twenty-five years,” writes James Gleick in Time Travel. “A Parisian antiques dealer stumbled upon the Gervais inventory in the twenties and bought the lot, including a single proof set of Côté’s cards in pristine condition. He had them for fifty years, finally selling them in 1978 to Christopher Hyde, a Canadian writer who came across his shop on rue de l’Ancienne-Comédie.”

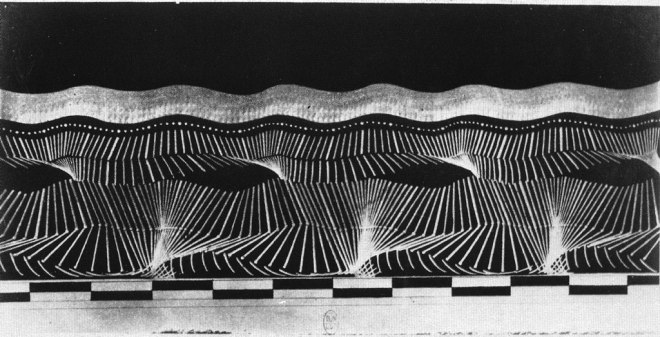

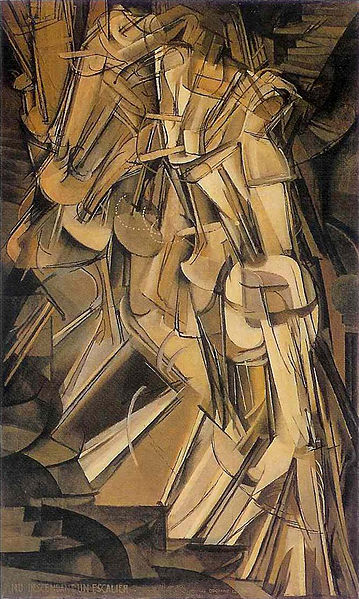

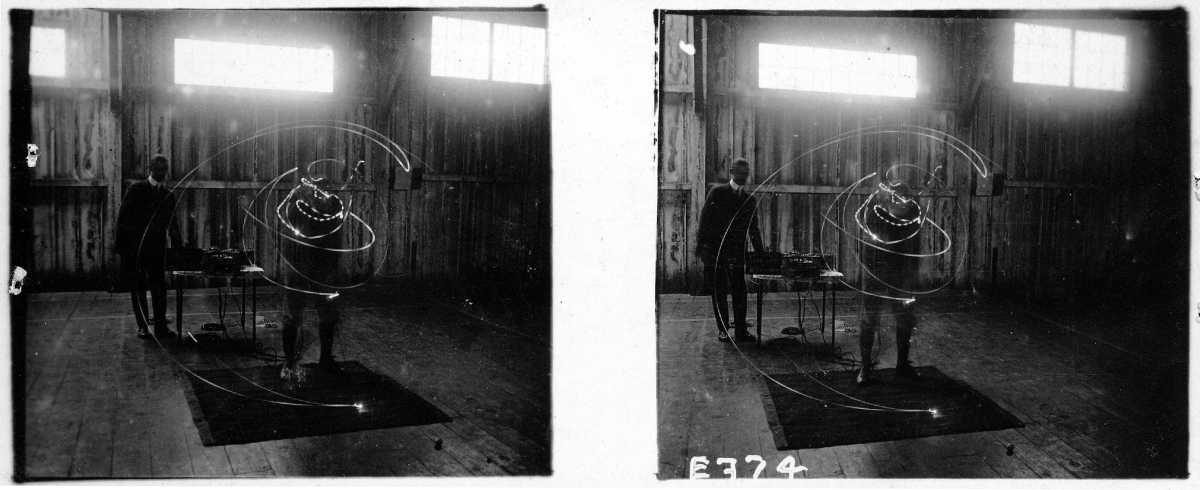

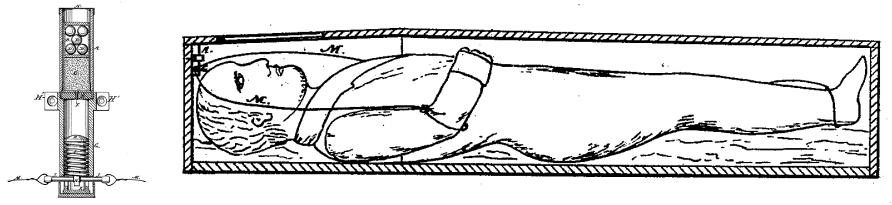

Hyde showed them to Isaac Asimov, who published them in 1986 as Futuredays, with a gentle commentary on what Côté had got right (widespread automation) and wrong (clothing styles). But maybe some of these visions are still ahead of us: