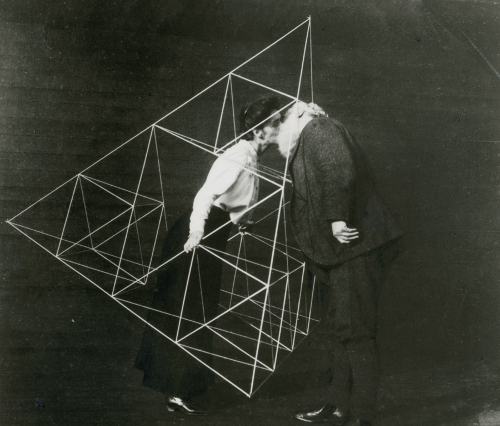

Alexander Graham Bell kisses his daughter Daisy inside a tetrahedral kite, October 1903.

Bang’s theorem holds that the faces of a tetrahedron all have the same perimeter only if they’re congruent triangles. Also, if they all have the same area, then they’re congruent triangles.

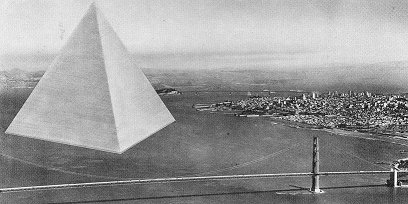

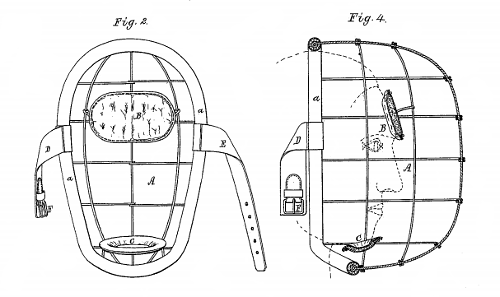

Buckminster Fuller proposed establishing a floating tetrahedron in San Francisco Bay called Triton City (below). It would have been assembled from modules, starting with a floating “neighborhood” of 5,000 residents, with an elementary school, a supermarket and a few specialty shops. Three to six neighborhoods would form a town, and three to seven towns would form a city. At each stage the corresponding infrastructure would be added: schools, civic facilities, government offices, and industry. A full-sized city might accommodate 100,000 people in a single building. He envisioned an even larger tetrahedron, with a million citizens, for Tokyo Bay.

The moral of Fuller’s 1975 book Synergetics was “Dare to be naïve.”