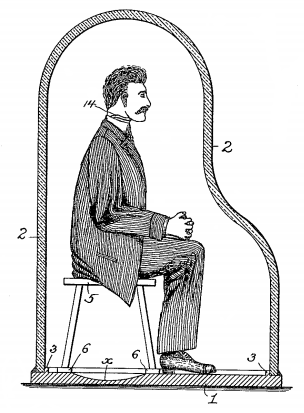

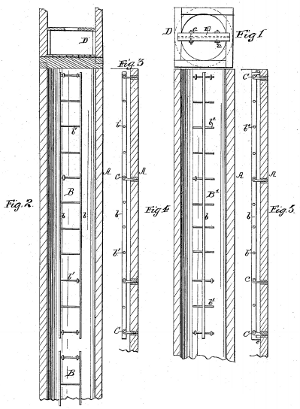

This is rather unpleasant. In 1883 John Fleck patented a “life-saving apparatus for privy-vaults,” “to provide a means of escape from the vaults should a person by accident fall therein.”

Apparently this was a problem. “In various sections of the United States deep vaults are commonly used, generally constructed of masonry, and, as is often the case, they are but imperfectly covered or otherwise protected at the top to guard against persons falling therein.”

Fleck’s solution is basically a ladder set into the wall of the vault. Good for him, I guess. I hope he wasn’t inspired by some personal tragedy.