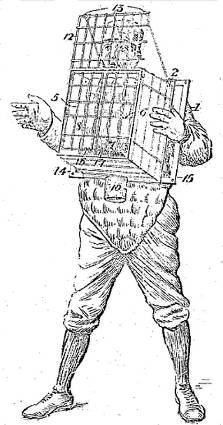

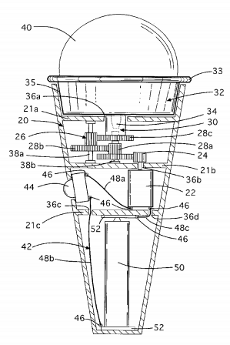

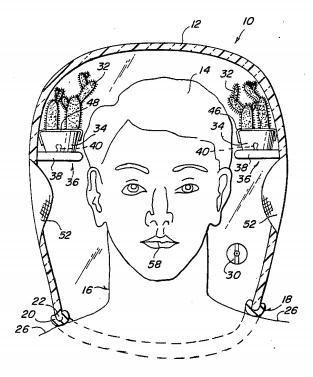

Patented in 1986, Waldemar Anguita’s “greenhouse helmet” is lined with live plants to provide oxygen for its wearer:

Plants, each within a pot, are placed within the dome. The carbon dioxide of the ambient air will mix with carbon dioxide breathed out by the person to be used by the plants to produce oxygen to be breathed in by the person.

Strangely, Anguita never explains why a person might want to do this.