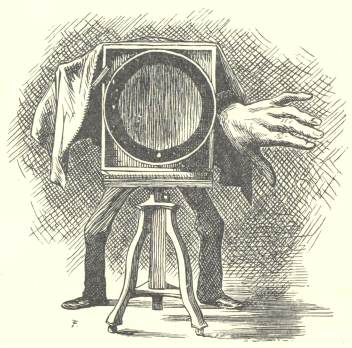

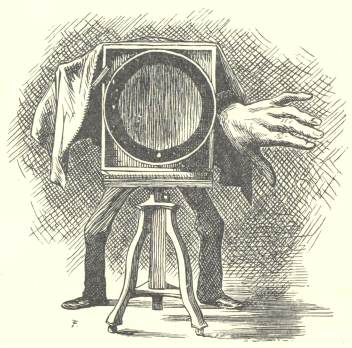

Lewis Carroll was an early enthusiast of photography, though he seems to have found the social aspects trying — he published this poem in 1857:

From his shoulder Hiawatha

Took the camera of rosewood,

Made of sliding, folding rosewood;

Neatly put it all together.

In its case it lay compactly,

Folded into nearly nothing;

But he opened out the hinges,

Pushed and pulled the joints and hinges,

Till it looked all squares and oblongs,

Like a complicated figure

In the Second Book of Euclid.

This he perched upon a tripod —

Crouched beneath its dusky cover —

Stretched his hand, enforcing silence —

Said, “Be motionless, I beg you!”

Mystic, awful was the process.

All the family in order

Sat before him for their pictures:

Each in turn, as he was taken,

Volunteered his own suggestions,

His ingenious suggestions.

First the Governor, the Father:

He suggested velvet curtains

Looped about a massy pillar;

And the corner of a table,

Of a rosewood dining-table.

He would hold a scroll of something,

Hold it firmly in his left-hand;

He would keep his right-hand buried

(Like Napoleon) in his waistcoat;

He would contemplate the distance

With a look of pensive meaning,

As of ducks that die ill tempests.

Grand, heroic was the notion:

Yet the picture failed entirely:

Failed, because he moved a little,

Moved, because he couldn’t help it.

Next, his better half took courage;

She would have her picture taken.

She came dressed beyond description,

Dressed in jewels and in satin

Far too gorgeous for an empress.

Gracefully she sat down sideways,

With a simper scarcely human,

Holding in her hand a bouquet

Rather larger than a cabbage.

All the while that she was sitting,

Still the lady chattered, chattered,

Like a monkey in the forest.

“Am I sitting still?” she asked him.

“Is my face enough in profile?

Shall I hold the bouquet higher?

Will it came into the picture?”

And the picture failed completely.

Next the Son, the Stunning-Cantab:

He suggested curves of beauty,

Curves pervading all his figure,

Which the eye might follow onward,

Till they centered in the breast-pin,

Centered in the golden breast-pin.

He had learnt it all from Ruskin

(Author of ‘The Stones of Venice,’

‘Seven Lamps of Architecture,’

‘Modern Painters,’ and some others);

And perhaps he had not fully

Understood his author’s meaning;

But, whatever was the reason,

All was fruitless, as the picture

Ended in an utter failure.

Next to him the eldest daughter:

She suggested very little,

Only asked if he would take her

With her look of ‘passive beauty.’

Her idea of passive beauty

Was a squinting of the left-eye,

Was a drooping of the right-eye,

Was a smile that went up sideways

To the corner of the nostrils.

Hiawatha, when she asked him,

Took no notice of the question,

Looked as if he hadn’t heard it;

But, when pointedly appealed to,

Smiled in his peculiar manner,

Coughed and said it ‘didn’t matter,’

Bit his lip and changed the subject.

Nor in this was he mistaken,

As the picture failed completely.

So in turn the other sisters.

Last, the youngest son was taken:

Very rough and thick his hair was,

Very round and red his face was,

Very dusty was his jacket,

Very fidgety his manner.

And his overbearing sisters

Called him names he disapproved of:

Called him Johnny, ‘Daddy’s Darling,’

Called him Jacky, ‘Scrubby School-boy.’

And, so awful was the picture,

In comparison the others

Seemed, to one’s bewildered fancy,

To have partially succeeded.

Finally my Hiawatha

Tumbled all the tribe together,

(‘Grouped’ is not the right expression),

And, as happy chance would have it

Did at last obtain a picture

Where the faces all succeeded:

Each came out a perfect likeness.

Then they joined and all abused it,

Unrestrainedly abused it,

As the worst and ugliest picture

They could possibly have dreamed of.

‘Giving one such strange expressions —

Sullen, stupid, pert expressions.

Really any one would take us

(Any one that did not know us)

For the most unpleasant people!’

(Hiawatha seemed to think so,

Seemed to think it not unlikely.)

All together rang their voices,

Angry, loud, discordant voices,

As of dogs that howl in concert,

As of cats that wail in chorus.

But my Hiawatha’s patience,

His politeness and his patience,

Unaccountably had vanished,

And he left that happy party.

Neither did he leave them slowly,

With the calm deliberation,

The intense deliberation

Of a photographic artist:

But he left them in a hurry,

Left them in a mighty hurry,

Stating that he would not stand it,

Stating in emphatic language

What he’d be before he’d stand it.

Hurriedly he packed his boxes:

Hurriedly the porter trundled

On a barrow all his boxes:

Hurriedly he took his ticket:

Hurriedly the train received him:

Thus departed Hiawatha.

He introduced it by writing, “In an age of imitation, I can claim no special merit for this slight attempt at doing what is known to be so easy. Any fairly practised writer, with the slightest ear for rhythm, could compose, for hours together, in the easy running metre of The Song of Hiawatha. Having then distinctly stated that I challenge no attention in the following little poem to its merely verbal jingle, I must beg the candid reader to confine his criticism to its treatment of the subject.”