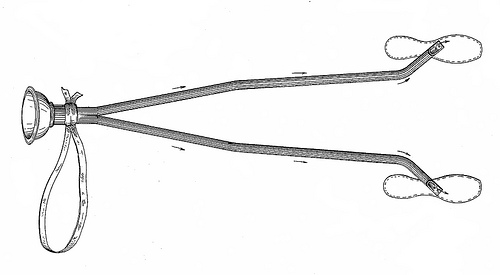

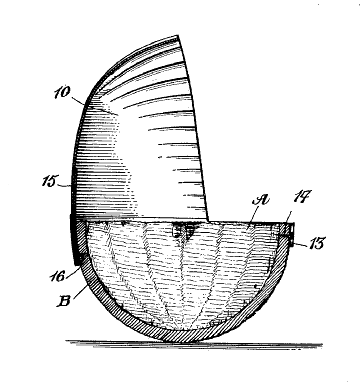

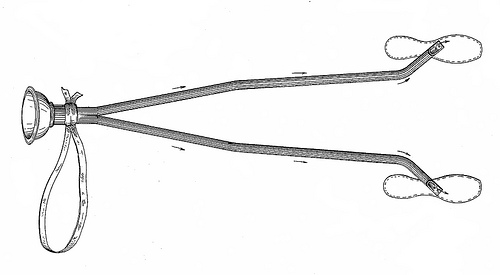

William Steiger had cold feet. But he also had a length of india-rubber tubing. So he snaked the latter down to the former, blew through the tube, and invented the “pedal calorificator,” a discreet way to breathe on one’s own feet.

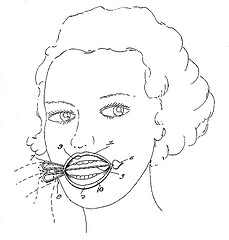

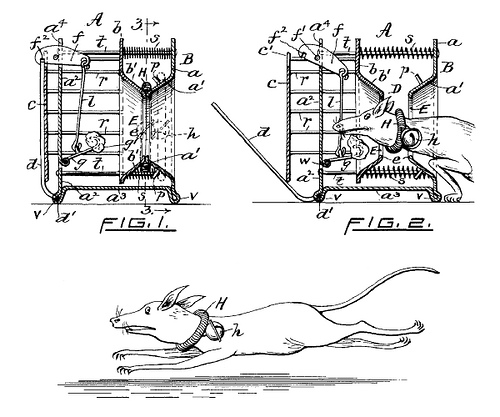

Steiger’s 1877 patent application is quaintly charming — apparently he had built a working model and worn it around Maryland for some time, finding that his body warmed the tubes so that his breath arrived in his shoes at 84°F. It was necessary only to exhale through his mouth, “an easy process, which I have ascertained practically may be kept up a long time, as, for example, for miles on a railroad-car, without much personal inconvenience.”