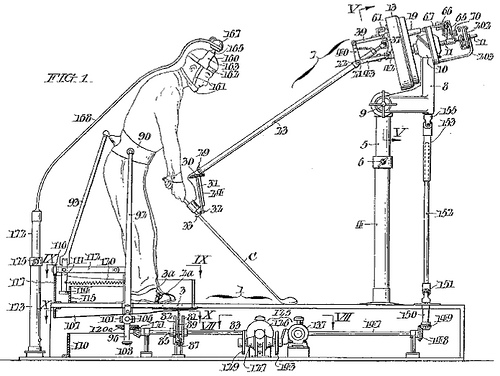

In 1769, after completing his robotic chess player, Wolfgang von Kempelen began a 20-year effort to a build a machine that could speak.

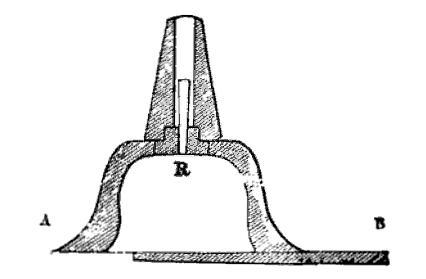

His first crude undertaking involved a bellows, bagpipe, and clarinet, and it could produce only vowels. A second was operated from a keyboard, but this permitted an unnatural overlapping of sounds.

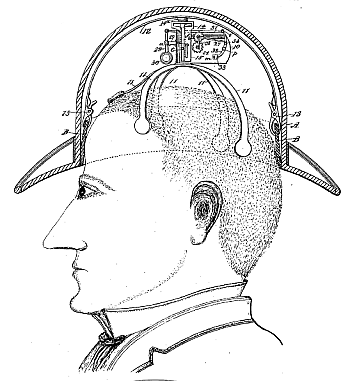

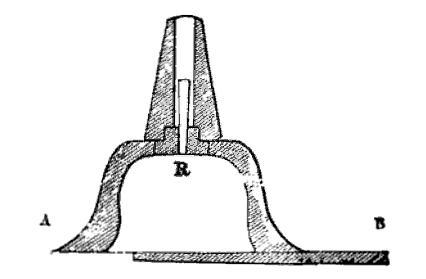

But von Kempelen began to study the human vocal tract more intensively, and this led to a winning third design, which had a “mouth,” a “throat,” a “nasal cavity,” and “nostrils.” It wasn’t perfect, but he trusted that listeners would forgive its errors because it sounded like a small child.

The finished machine could pronounce monotone phrases in French, Italian, English, Latin, and limited German, including Constantinopolis, vous êtes mon ami, je vous aime de tout mon coeur, venez avec moi à Paris, Leopoldus secundus, and Romanorum imperator semper Augustus.

His work wasn’t wasted. Before his death in 1804, Von Kempelen published a comprehensive account of his researches, and in 1837 Sir Charles Wheatstone took up the project. His efforts in turn inspired Alexander Graham Bell — and, eventually, the telephone.