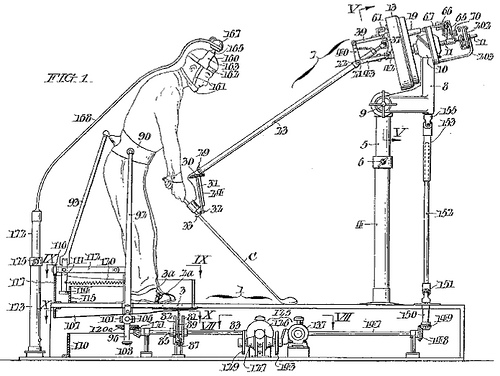

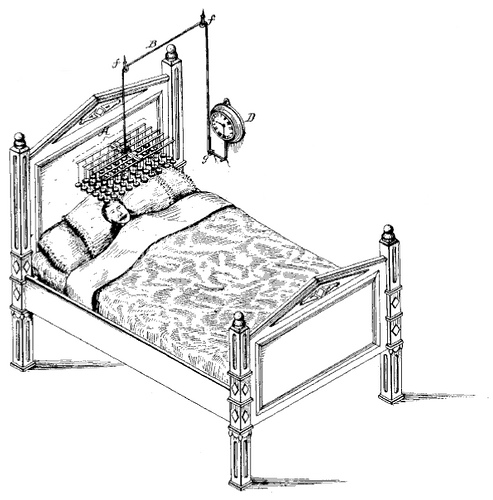

If a conventional alarm clock doesn’t wake you, consider this Improved Device for Waking Persons from Sleep, patented in 1882 by Samuel Applegate.

It suspends a frame “directly over the head of the sleeper” from each of whose cords hangs “a small block of light wood, preferably cork.”

“When it falls it will strike a light blow, sufficient to awaken the sleeper, but not heavy enough to cause pain.”

If that’s not dangerous enough, “By a simple connection between the cord B and the key of a self-lighting gas-burner, provision may be made for turning on and lighting the gas in the room at the same time that the sleeper is awakened.”