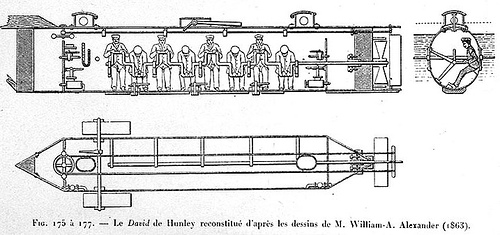

The Confederate navy had a working submarine during the Civil War. Powered by a hand crank, the 40-foot H.L. Hunley managed to sink an 1,800-ton sloop-of-war in Charleston harbor in 1864, a historic first, but then herself sank.

Little is known about the sub’s crew, but one story held that the commander, Lt. George E. Dixon, had survived the Battle of Shiloh because a Union bullet struck a coin in his pocket. His sweetheart, it was said, had given him the coin “for protection.” This was considered a family legend until 2002, when a forensic anthropologist investigating the Hunley‘s remains discovered a healed injury to Dixon’s hip bone.

Near Dixon’s station another researcher found a misshapen $20 gold piece, minted in 1860, with this inscription:

Shiloh

April 6 1862

My life Preserver

G. E. D.