The Great Bell of Dhammazedi may have been the largest bell ever made, reportedly weighing 300 metric tons.

Unfortunately, there’s no way to confirm its size — after the Portuguese removed it from a Myanmar temple in 1608, it was lost in a river.

The Great Bell of Dhammazedi may have been the largest bell ever made, reportedly weighing 300 metric tons.

Unfortunately, there’s no way to confirm its size — after the Portuguese removed it from a Myanmar temple in 1608, it was lost in a river.

People were retouching photos long before PhotoShop. In 1938 Nikolai Yezhov, a leader of the Soviet secret police, fell out of favor with Stalin — and literally disappeared.

In Boston’s Museum of Science is a computer made of Tinkertoys that plays tic-tac-toe.

It has never lost a game.

Victoria Crater, on Mars. The black dot on the rim, at about the 10 o’clock position, is the Mars rover Opportunity. Expected to fail after 90 days, it has been exploring faithfully for more than three years.

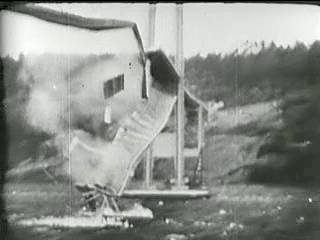

On Nov. 7, 1940, photographer Leonard Coatsworth was halfway across Washington’s Tacoma Narrows Bridge when he felt it move strangely:

“Just as I drove past the towers, the bridge began to sway violently from side to side. Before I realized it, the tilt became so violent that I lost control of the car. … I jammed on the brakes and got out, only to be thrown onto my face against the curb… Around me I could hear concrete cracking. … The car itself began to slide from side to side of the roadway.”

Gripping the curb, he crawled 500 yards back toward the toll plaza, turned and watched his car plunge into the Narrows. With it went his daughter’s dog, Tubby, who was too terrified to jump out.

The bridge had been competently designed, with supports by Golden Gate designer Leon Moisseiff, but no one had counted on its twisting and buckling in the wind.

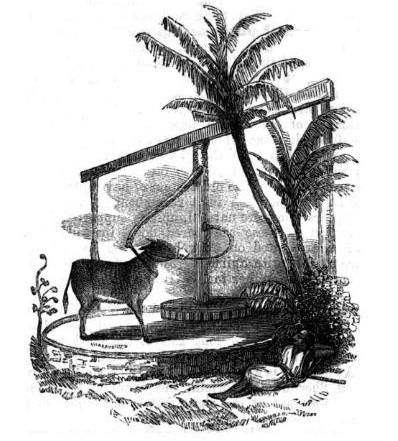

Passing some cemeteries and public fountains, we came to the outskirts of the city, which consist chiefly of gardens producing olives, oranges, raisins and figs, irrigated by creaking water-wheels worked by donkeys. To one of these the droll contrivance which attracted our notice was affixed. The donkey who went round and round was blinded, and in front of him was a pole, one end of which was fixed to the axle and the other slightly drawn towards his head-gear and there tied; so that, from the spring he always thought somebody was pulling him on. The guide told us that idle fellows would contrive some rude mechanism so that a stick should fall upon the animal’s hind quarters at every round, and so keep him at work whilst they went to sleep under the trees.

— Albert Smith, A Month at Constantinople, 1850

“Drill for oil? You mean drill into the ground to try and find oil? You’re crazy.” — Associates of Edwin L. Drake, refusing his suggestion, 1859

On Aug. 11, 1966, a fishing boat came upon a badly bruised man floating in the water off Brest, France, clutching an inflatable life raft. He identified himself as Josef Papp, a Hungarian-Canadian engineer, and claimed he had just bailed out of a jet-powered submarine that had crossed the Atlantic in 13 hours.

The media laughed at this, but Papp insisted he had built a cone-shaped sub in his garage that could reach 300 mph using the same principle as a supercavitating torpedo. He even wrote a book, The Fastest Submarine, to answer his critics … but somehow this failed to explain how the sub worked, or why plane tickets to France had been found in his pocket, or why a man matching his description had been seen boarding a plane to France hours earlier.

For what it’s worth, Papp did patent a number of other inventions, including a fuel mixture composed from inert noble gases. So maybe he was telling the truth.

In 1896, New Jersey clam diggers Frank Samuelsen and George Harbo decided to make a name for themselves by rowing across the Atlantic Ocean. On June 6 they set out from the Battery in an 18-foot oak rowboat with a compass, a sextant, and a copy of the Nautical Almanac. They reached England’s Isles of Scilly in 55 days, a record that still stands.

Ironically, on the way home their passenger steamer ran out of coal. The pair launched their boat and rowed back to New York.