Someone make a note, in case we ever run out of power:

In 1990 the Internet Engineering Task Force proposed a way to send Internet messages by homing pigeon.

It was used — once — to transmit a message in Bergen, Norway.

Someone make a note, in case we ever run out of power:

In 1990 the Internet Engineering Task Force proposed a way to send Internet messages by homing pigeon.

It was used — once — to transmit a message in Bergen, Norway.

One more reason not to mess with Leonardo da Vinci — he designed this armored tank at the Château d’Amboise around 1516.

In the UH-1 Iroquois helicopter, a hexagonal nut holds the main rotor to the mast. If it were to fail in flight, the helicopter’s body would separate from its rotor.

Engineers call it the “Jesus nut.”

You can write a message to future generations at the KEO project. It’ll be launched on a satellite that won’t return to Earth for 50,000 years.

Even more ambitious is the LAGEOS satellite, which will re-enter our atmosphere in 8.4 million years bearing a plaque that shows the arrangement of the continents. Let’s hope our descendants still have catcher’s mitts.

Web sites with a Google PageRank of 10:

And, of course, Google itself.

Douglas Adams’ “rules that describe our reactions to technologies”:

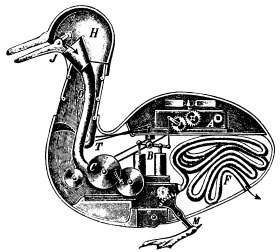

Vaucanson’s Shitting Duck was one of the more unsavory products of the French Enlightenment.

When it was unveiled by Jacques de Vaucanson in 1739, thousands watched the “canard digérateur” stretch its neck to eat grain from a hand. The food then dissolved, “the matter digested in the stomach being conducted by tubes, as in an animal by its bowels, into the anus, where there is a sphincter which permits it to be released.” These inner workings were all proudly displayed, “though some ladies preferred to see them decently covered.”

Why make fake duck shit when the world is so well supplied with the real thing? It was part of the Enlightenment’s transition from a naturalistic to a mechanical worldview. Suddenly a duck was not a God-given miracle but a machine made of meat, and complex automatons carried the promise of mechanized labor, stirring a cultural revolution.

Goethe mentioned Vaucanson’s automata in his diary, and Sir David Brewster called the duck “perhaps the most wonderful piece of mechanism ever made.” Sadly, the whole thing was a fake: The droppings were prefabricated and hidden in a separate compartment. Back to the drawing board.

Actual questions asked in Microsoft job interviews:

At the end they ask, “What was the hardest question asked of you today?” My answer: “Why do you want to work at Microsoft?”

The 10 oldest currently registered dot-com domains:

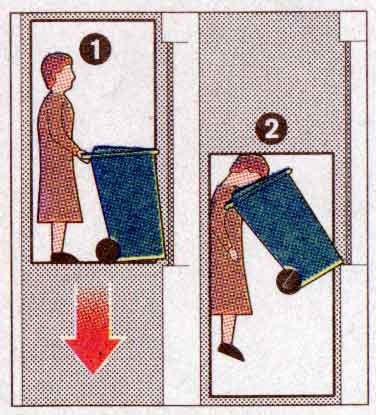

From the Hall of Technical Documentation Weirdness:

“Wear a bad sweater dress, suffer the consequences.”