In 1998, tides exposed a ring of Bronze Age timbers off the coast of Norfolk.

The monument appears to have been created in 2049 B.C., probably in a salt marsh that was later overrun by the sea.

What was its purpose? Who knows?

In 1998, tides exposed a ring of Bronze Age timbers off the coast of Norfolk.

The monument appears to have been created in 2049 B.C., probably in a salt marsh that was later overrun by the sea.

What was its purpose? Who knows?

latibulate

v. to hide oneself in a corner

[A]dvertising will in the future world become gradually more and more intelligent in tone. It will seek to influence demand by argument instead of clamour, a tendency already more apparent every year. Cheap attention-calling tricks and clap-trap will be wholly replaced, as they are already being greatly replaced, by serious exposition; and advertisements, instead of being mere repetitions of stale catch-words, will be made interesting and informative, so that they will be welcomed instead of being shunned; and it will be just as suicidal for a manufacturer to publish silly or fallacious claims to notoriety as for a shopkeeper of the present day to seek custom by telling lies to his customers.

— T. Baron Russell, A Hundred Years Hence, 1906

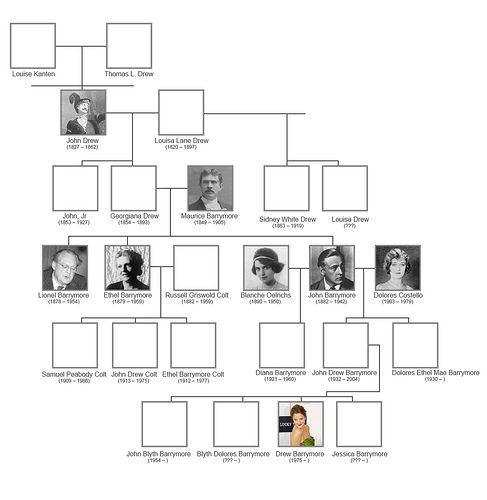

On her Broadway debut in 1940, Diana Barrymore wired her father, John:

DEAREST DADDY, THANK YOU FOR THE APPLE FLOWERS AND WIRES … SO DADDY DARLING I AM DOING MY BEST TO CARRY ON THIS STINKING TRADITION.

Herbert Blythe had adopted the name Maurice Barrymore in 1872 to spare his father the “shame” of having a son in such a “dissolute” vocation as acting.

His great-granddaughter, Drew Barrymore, has earned more than $1 billion in box-office grosses at age 35.

In 1808, a French gentleman bought 2,700 acres in Georgetown, N.Y., and erected a chateau on the highest hill. Evidently he was massively wealthy, landscaping the grounds extensively and ordering a hamlet built on the estate, after the fashion of the great French nobles. And he seemed fearful for his safety, securing the house against gunfire and clearing the woods around it.

He roved the estate on horseback, attended by armed servants, and was described as erect, agile, and commanding. When asked to muster for the local militia he responded with outrage, saying he had led a division and participated in making three treaties, but he gave no other clues to his identity. He followed closely the progress of the War of 1812 and of Napoleon, whose ascendancy he evidently feared; when the Corsican met disaster in Russia he returned abruptly to France.

Who was this man? He gave his name as Louis Anathe Muller, but he guarded his true identity closely. Was he a French duke? A son of Charles X? The future king himself? With only circumstantial evidence, there’s no way to be certain. After Waterloo he sold the estate for a fraction of its value, and he never returned to New York.

“Nobody now fears that a Japanese fleet could deal an unexpected blow on our Pacific possessions. … Radio makes surprise impossible.”

— Josephus Daniels, former U.S. secretary of the navy, Oct. 16, 1922

Well, you’ve gone and murdered someone again. And this time you’ve done it in Elephantistan, which is renowned for its peculiar justice system.

The jury is divided, so you will decide your own fate. You’re presented with two urns, each of which contains 25 white balls and 25 black ones. Blindfolded, you must choose an urn at random and then draw a ball from it; a black ball means death, but a white one means you go free.

Tradition gives you the option to distribute the balls however you like between the two urns before you don the blindfold. This is thought to be a formality, as the total proportion of white balls to black does not change.

What should you do?

Reflect, Socrates; you may have to deny your words.

I have reflected, I said; and I shall never deny my words.

Well, said he, and so you say that you wish Cleinias to become wise?

Undoubtedly.

And he is not wise as yet?

At least his modesty will not allow him to say that he is.

You wish him, he said, to become wise, and not to be ignorant?

That we do.

You wish him to be what he is not, and no longer to be what he is?

I was thrown into consternation at this.

Taking advantage of my consternation he added: You wish him no longer to be what he is, which can only mean that you wish him to perish. Pretty lovers and friends they must be who want their favourite not to be, or to perish!

— Plato, Euthydemus

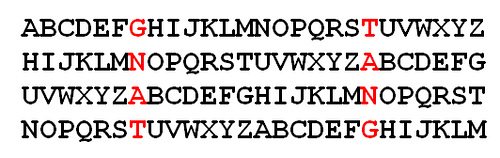

Advance each letter in GNAT 13 places through the alphabet and you’ll get GNAT reversed — or TANG:

9 + 9 = 18; 9 × 9 = 81

24 + 3 = 27; 24 × 3 = 72

47 + 2 = 49; 47 × 2 = 94

497 + 2 = 499; 497 × 2 = 994