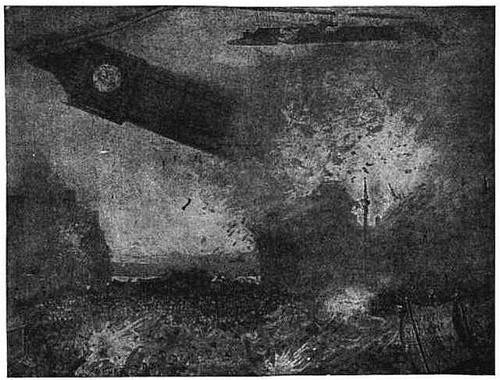

From Hastings, on the English shore, to the French cliffs, is more than fifty miles, and they are of course hid from each other by the convexity of the earth. On the evening of the 26th of July, 1798, the coast of France was visible at Hastings to the naked eye for several leagues, as though only a few miles off. Every spot was distinctly seen from Calais, Boulogne, as far as Dieppe. With the aid of a telescope, the fishing boats were seen at anchor, the different colors of the land upon the heights were distinguishable, and the sailors pointed out the places they were in the habit of visiting. The account of the phenomenon was drawn up by Mr. Lanham, a fellow of the Royal Society, who was an eye witness.

— The Thomsonian Recorder, Aug. 30, 1834