There was an old lady from Slough

Who developed a terrible cough.

She drank half a pint

Of warm honey and mint,

But, sadly, she didn’t pull through.

(Thanks, Rikki.)

There was an old lady from Slough

Who developed a terrible cough.

She drank half a pint

Of warm honey and mint,

But, sadly, she didn’t pull through.

(Thanks, Rikki.)

The United Equipment Company sells bulldozers — but you might have guessed that from its headquarters building in Turlock, Calif., which is shaped like an oversized yellow Caterpillar D6. Built in 1977, it’s two stories tall and contains six rooms. See also Yogi Bear’s Dream.

The fastest temperature drop in history occurred in Rapid City, S.D., when the mercury plunged 47°F (26°C) in 5 minutes on Jan. 10, 1911.

Interestingly, the fastest temperature rise in history occurred in the same city 32 years later, when it jumped 49°F (27°C) in 2 minutes on Jan. 22, 1943.

Dubious but worth recording: A tract dated 1622 reports a vast war of starlings over Cork, Ireland, Oct. 12-14, 1621. Armies of birds had reportedly converged from the east and west some four or five days before, and on Oct. 12 “they forthwith, at one Instant, took Wing, and so mounting up into the Skies, encountered one another with such a terrible Shock, as the Sound amazed the whole City and the Beholders,” until “there fell down in the City, and into the Rivers, Multitudes of Starlings or Stares, some with Wings broken, some with Legs and Necks broken, some with Eyes picked out, some their Bills thrust into the Breast and Sides of their Adversaries, on so strage [sic] a Manner, that it were incredible, except it were confirmed by Letters of Credit, and by Eye-Witnesses with that Assurance which is without all Exception.”

The birds adjourned, for some reason, on Sunday, though visitors from Suffolk reported seeing a similar war over remote woods there. On Monday the fight resumed over Cork, and this time the dead included a kite, a raven, and a crow.

I can’t find the original pamphlet, but it’s referenced by Johns Hopkins (1905), the London Library (1888), the New York State Library (1882), and the Bodleian Library (1860), among others. Starlings do have a colorful history — see Oops and Fragments of Night.

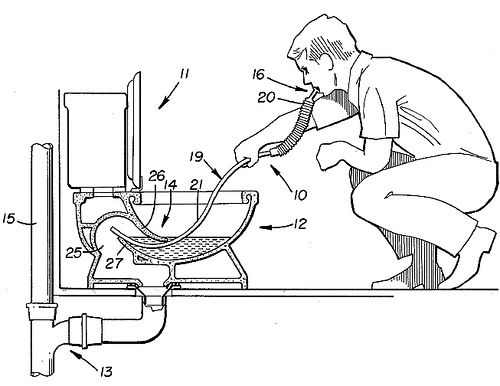

Okay, there’s good news and bad news. The good news is that we’ve found a safe source of fresh air for people trapped in high-rise hotel fires. The bad news is that they have to feed a breathing tube into a vent pipe in the sewer line.

William Holmes’ 1981 brainstorm probably would have saved many lives, but even a guest surrounded by toxic smoke has some natural squeamishness.

muliebrity

n. the state of being a woman

‘As I was going over the bridge the other day,’ said an Irishman, ‘I met Pat Hewins. “Hewins,” says I, “how are you?”

“Pretty well, thank you, Donnelly,” says he.

“Donnelly,” says I, “that’s not my name.”

“Faith, then, no more is mine Hewins.”

‘So with that we looked at each other agin, an’ sure enough it was nayther of us.’

— Melville D. Landon, Wit and Humor of the Age, 1888

Abe Lincoln never actually slept in the Lincoln Bedroom, but his ghost seems to spend a lot of time there:

“If you see him again,” Reagan told Maureen, “send him down the hall. I have some questions.”

“The more original a discovery, the more obvious it seems afterward.” — Arthur Koestler

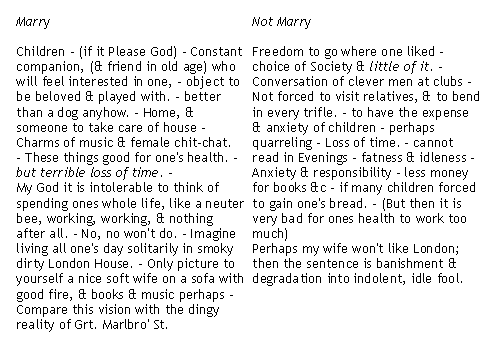

In July 1838, Charles Darwin was considering whether to propose to his cousin, Emma Wedgwood. Ever the rationalist, drew up a balance sheet:

At the bottom he wrote “Marry – Marry – Marry Q.E.D.” They were wed in January.