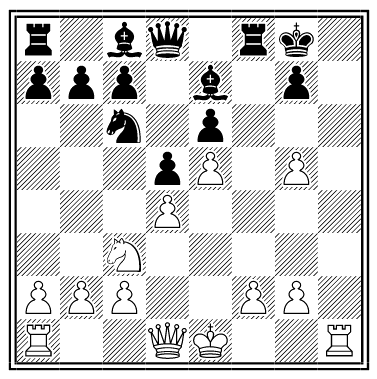

What’s unusual about this game by Joseph Blackburne, apart from its characteristic brilliance?

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Bg5 Be7 5.Bxf6 Bxf6 6.Nf3 O-O 7.Bd3 Nc6 8.e5 Be7 9.h4 f6 10.Ng5 fxg5 11.Bxh7+ Kxh7 12.hxg5 Kg8

13.Rh8+ Kxh8 14.Qh5+ Kg8 15.g6 Rf5 16.Qh7+ Kf8 17.Qh8#

“Move for move I played it exactly in the same way twice in one week, once at Hastings and once at Eastbourne, in the year 1894.”