George Story was aptly named: He appeared as a baby in the first issue of Life magazine in 1936, and he died 63 years later — as the magazine announced it was ceasing publication.

A Question Without an Answer

In 1905, the Ingersoll company engaged Sam Loyd to invent a puzzle to promote its new dollar watch. Loyd sent the illustration above and asked:

How soon will the hour, minute and second hands again appear equal distances apart?

The company advertised the puzzle in Scribner’s in June, promising a free watch to the first 10,000 correct respondents. “The full problem is stated above,” the ad ran, “and no further information can be given in fairness to all contestants.” Further, it said, Loyd’s solution “is locked in our safe, inaccessible to any one.”

Perhaps it still is — I can’t find any record of a solution to the puzzle. I offer it here for what it’s worth.

06/02/2024 UPDATE: Reader Alexander Rodgers writes:

I had to give it a go. To summarise my findings:

- It isn’t actually possible for the three hands of a clock to be perfectly equally spaced apart, barring some unusual hand-moving mechanisms. Even the time shown in the picture isn’t perfectly equal.

- The answer therefore probably hinges on the phrase “appear equal”.

- That’s subjective, so I present three answers, and one can pick which is the earliest time that “appears” equal:

- 0h 43m 23s later, at 3:37:58

- 2h 54m 34s later, at 5:49:09

- 6h 10m 50s later, at 9:05:25.

The company may claim the puzzle is present in full. But on attempting it, I found it difficult to determine what assumptions the puzzle is working under.

I started by assuming two things:

- That “equal distances apart” means each pair of hands forms an angle of exactly 120 degrees.

- That the hands move continuously, rather than ‘ticking’ in some way.

Under these assumptions though, the example time pictured isn’t actually at equal distances.

The time pictured is about 2:55:35. I found the exact time at which the second and minute hands are exactly 120º: it is 2:55.34.576… (Specifically, it is (171+2/3)/59 hours after twelve.) At this time:

The hour hand has moved (2 + 54/60 + 34.576/3600)/12 revolutions or 87.29º;

The minute hand has moved 2 full revolutions, plus another (54/60 + 34.576/3600) or 327.46º;

The second hand has moved many revolutions plus 34.576/60 or 207.46º.

So the three angles are 120º exactly, 120.17º, and 119.83º. Any times close to this time might get another pair bang on but the second/minute pair will be off.

In fact, I have determined that under my two assumptions there are no points in time at all where the hands truly are equal distances apart.

Proof:

Measure time (t) in “hours past twelve”. Then the number of revolutions of each hand at time t is:

S(t) = 60t for the second hand,

M(t) = t for the minute hand, and

H(t) = (1/12)t for the hour hand.

We can take the difference in any two of these functions. If the result is a whole number plus 1/3, then the angle between them is 1/3 of a full circle or 120º. If the result is a whole number plus 2/3, then the angle between them is also 120º. But if it’s anything else, then the angle isn’t 120º.

So, say for the hour/minute pair, the angle is 120º if and only if:

(M(t) – H(t))t = k +1/3 OR (M(t) – H(t))t = k +2/3, where k is an integer

We can rearrange these as:

t = (k +1/3)/(11/12) OR t = (k +2/3)/(11/12)

We can then just plug in all integers and output a list of valid times t. (We don’t need to do all integers, since t really is a number of at least 0 and less than 12. We start with k=0, and increase it until the resulting t is greater than 12.)

This generates a list of 22 times in a full cycle when the hour and minute hand are exactly 120º apart.

We can do the same with the minute and second hands. We get a list of 1417 times when they are exactly 120º apart. We then compare our two lists looking for times when both of these pairs are 120º apart.

But no values appear in both lists. Therefore there is no time then the hands are truly “equal distances apart”.

So to find an answer to this puzzle, we need to remove at least one of our two assumptions. I first tried removing the “exactly 120º” assumption, and instead went hunting for times when the hands would look equally spaced apart to the naked eye. After all, the puzzle did say “appear equal distances apart”.

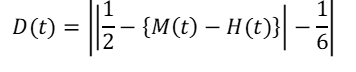

For any two pairs of hands, I made a function that is zero if the angle is exactly 120º, and a positive number if not, specifically being a larger number the further we get from 120º. For, say, the minute/hour pair, the function is:

(where |x| is absolute value of x and {x} is the fractional part of x)

This function works as follows: Take the difference in total revolutions at time t. Discard the integer component and just keep the fractional part. For the angle to be 120º, then this figure is either 1/3 or 2/3; either way it is “1/6 away from 1/2, though in either direction”. The function gives zero when the angle is exactly 120º, and increases as the angle drifts from this goal up to a maximum output of 1/3.

I defined “distance off perfect” as being the largest of the three of these functions.

For every time between zero and twelve, we can find the worst result of this function for the three pairs. This gives the following graph:

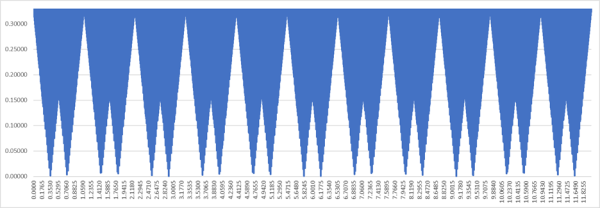

I zoom in the y-axis so we can see how close those spikes get to zero:

I can then read points off the graph that are close to zero, and those will be close to ‘equal distance’.

The next times of day after 2:55:35 that might look good are:

- 3 hours, 37 minutes, 58.15 seconds after midnight. Positions are 348.91º, 227.82º, 108.98º; angles are 118.83º, 121.10º, and 120.07º. (So decent, but not within 1 degree.)

- 5 hours, 49 minutes, 9.16 seconds after midnight. Positions are 54.94º, 294.92º, 174.58º; angles are 119.64º, 120.34º, and 120.02º.

- 9 hours, 5 minutes, 25.45 seconds after midnight. Positions are 152.54º, 32.54º, 272.71º; angles are 120º exactly, 120.17º, and 119.83º.

The last position gives exactly the same angles as the example image in the puzzle. This is because it is exactly the same amount of time before twelve as the example in the question is after 12, and this produces a mirror image.

I don’t have as much to say about removing the assumption about the hand moving continuously, as I don’t know enough about how clocks work to give a full answer. But I think it doesn’t help us find a perfect moment of equal distances. My understanding of a ticking clock mechanism is that it will jump forward every second but it will never produce a position that was unseen from those in the continuous model. You’d need some sort of clock where each hand is jumping on a different mechanism?

Overall, if I was submitting an answer to the competition, I’d submit 5:49:09. If the organisers noted the hands weren’t perfectly equal distances apart, I’d rebut that neither were they in their own example.

(Thanks, Alex. I wonder now whether Loyd had in mind some “trick” solution such as noon or midnight.)

In a Word

remontado

n. one who has left civilization and returned to the wilderness

Sarah Bishop was a young lady of considerable beauty, a competent share of mental endowments and education; she possessed a handsome fortune, but was of a tender and delicate constitution, enjoyed but a precarious state of health, and could scarcely be comfortable without constant recourse to medicine and careful attendance. She was often heard to say that she had no dread of any animal on earth but man. Disgusted with her fellow-creatures, she withdrew from all human society, and at the age of about twenty-seven, in the bloom of life, resorted to the mountains which divide Salem from North Salem: where she has spent her days to the present time, in a cave, or rather cleft of the rock, withdrawn from the society of every living being.

— G.H. Wilson, The Eccentric Mirror, 1813

Quine’s Paradox

“Yields a falsehood when preceded by its quotation” yields a falsehood when preceded by its quotation.

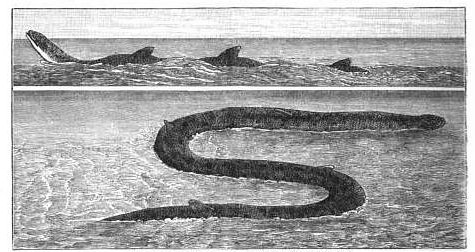

A Watery Welcome

On May 13, 1872, the barque St. Olaf was sailing from Newport to Galveston when a crewman called out that “he saw something rising out of the water like a tall man”:

On a nearer approach we saw that it was an immense serpent, with its head out of the water, about 200 feet from the vessel. He lay still on the surface of the water, lifting his head up and moving the body in a serpentine manner. We could not see all of it, but what we could see from the after-part to the head was about 70 feet long, and of the same thickness all the way, excepting about the head and neck, which were smaller, and the former flat like the head of a serpent. It had four fins on its back, and the body of a yellow, greenish colour, with brown spots all over the upper part, and underneath white.

The weather was calm, the sea smooth. “The whole crew were looking at it for fully ten minutes before it moved away,” Captain A. Hassel reported later. “It was about 6 feet in diameter.”

Easy as Pie

Now I will a rhyme construct,

By chosen words the young instruct.

Cunningly devised endeavour,

Con it and remember ever.

Widths in circle here you see,

Sketched out in strange obscurity.

Count the letters in each word.

The Wooden Horse

In 1943, authorities at a German POW camp in Poland discovered that three prisoners were missing. A considerable space separated the prisoners’ huts from the perimeter fence, so at first it wasn’t clear how they’d escaped.

But the three inmates had something in common — all three had exercised during the day on a vaulting horse in the yard. On investigating, the Germans discovered a 100-foot tunnel leading from that spot to an opening beyond the fence.

The truth became clear. Each day, the prisoners had carried the horse to the same spot with a man hidden inside. While they exercised, the hidden man had used a bowl to lengthen the tunnel, then hid again in the horse as it was carried back inside. The Germans had used siesmographs to detect tunneling, but the prisoners’ vaulting had masked the sounds of their digging.

All three escapees — Eric Williams, Michael Codner, and Oliver Philpot — reached neutral Sweden and were reunited with their families.

Turnabout

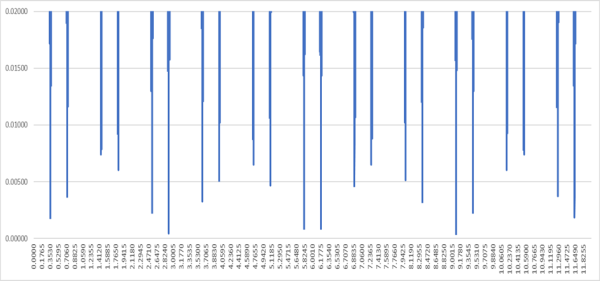

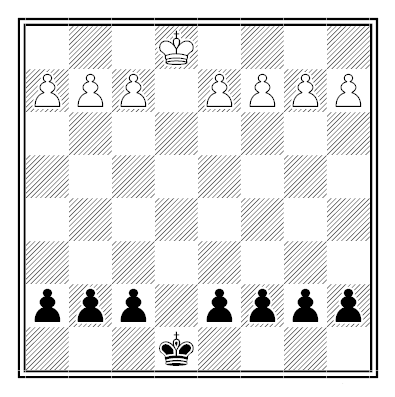

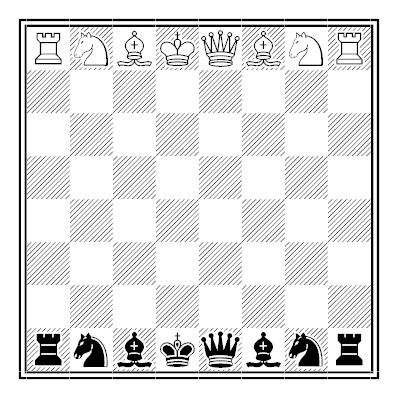

José Silva and João Rafael devised this chess game to demonstrate at the 1978 Portuguese Junior Championship. The game is spurious, but the moves are legal:

1. a3 h6 2. b3 g6 3. c3 f6 4. d3 e6 5. e3 d6 6. f3 c6 7. g3 b6 8. h3 a6 9. a4 b5 10. a5 b4 11. c4 d5 12. c5 d4 13. e4 f5 14. e5 f4 15. g4 h5 16. g5 h4 17. Nc3 dxc3 18. Ra3 bxa3 19. b4 Nf6 20. exf6 Rh6 21. gxh6 g5 22. b5 g4 23. b6 g3 24. d4 e5 25. Bb5 axb5 26. d5 Bg4 27. hxg4 e4 28. d6 e3 29. Qd5 cxd5 30. Ne2 d4 31. Nxd4 Be7 32. dxe7 Qxe7 33. Bb2 Qe4 34. fxe4 cxb2 35. a6 b4 36. Nc2 b3 37. Ke2 bxc2 38. Rd1 Nd7 39. g5 Rc8 40. g6 Rc7 41. bxc7 Nb6 42. cxb6 h3 43. Rd7 Kxd7 44. Kd3 Ke6 45. e5 Kf5 46. Kc4 Ke4 47. Kc5 Kd3 48. Kd6 Kd2 49. Kd7 Kd1 50. Kd8 f3 51. g7 g2 52. h7 a2 53. f7 h2 54. b7 f2 55. a7 e2 56. e6 Kd2 57. e7 Kd1

Okay so far? Now 58. a8=R h1=R 59. b8=N g1=N 60. c8=B f1=B 61. e8=Q e1=Q 62. f8=B c1=B 63. g8=N b1=N 64. h8=R a1=R:

The players agree to a draw.

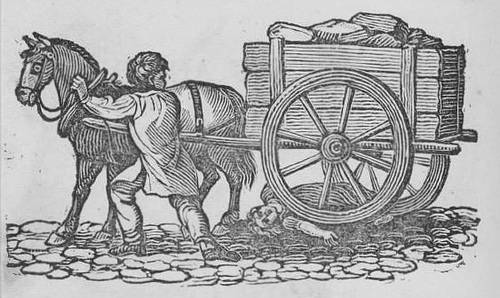

Teach Your Children Well

Safety lessons for young people, from The Book of Accidents (1831):

“Horses are very dangerous, but most useful animals. To be kicked by them is almost certain death.”

“Careless children, in spite of warning, often run across the street when carts and carriages are near, and are knocked down and run over.”

“Many children delight in teazing dogs, and without caution go too near them, by which they get miserably torn and mangled.”

(More to come.)

“Sucked to Death by a Bear”

Aftermath of a bear attack, Dhaka, Bengal, recounted by a Captain Williamson in The Terrific Register, 1825:

We found her husband extended on the ground, his hands and feet, as I before observed, sucked and chewed into a perfect pulp, the teguments of the limbs in general drawn from under the skin, and the skull mostly laid bare; the skin of it hanging down in long strips; obviously effected by their talons. What was most wonderful was, that the unhappy man retained his senses sufficiently to describe that he had been attacked by several bears, the woman said seven, one of which had embraced him while the others clawed him about the head, and bit at his arms and legs, seemingly in competition for the booty.

“We conveyed the wretched object to a house, where in a few hours, death relieved him from a state, in which no human being could afford the smallest assistance!”