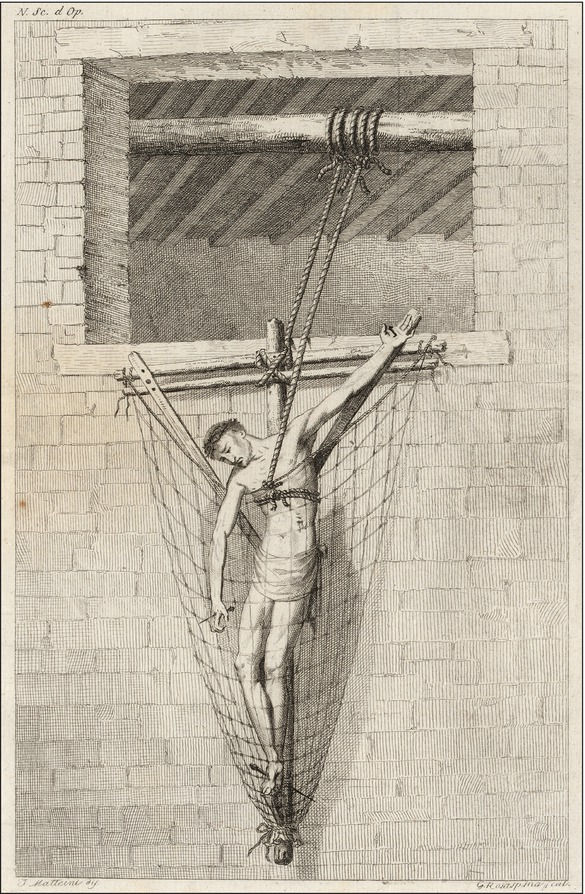

Sentenced in 1964 to life in prison, anti-apartheid activist Ahmed Kathrada got permission during his confinement to pursue a history degree through the University of South Africa. He used his access to books and writing materials to compile a series of secret notebooks in which he recorded quotations that inspired him. Together they form what used to be called a commonplace book — a series of personal memoranda that, taken together, illuminate the spirit of the compiler:

Ofttimes the test of courage becomes rather to live than to die. — Vittorio Alfieri

It is almost a definition of a gentleman to say he is one who never inflicts pain. — Cardinal Newman, The Idea of a University Defined (1873)

One owes respect to the living; but to the dead one owes nothing but the truth. — Voltaire

The triumph of wicked men is always short-lived. — Honore de Balzac, The Black Sheep

(Form of oath-taking among Shoshone Indians is:) The earth hears me. The sun hears me. Shall I lie?

Conrad wrote that life sometimes made him feel like a cornered rat waiting to be clubbed.

Nobody knows what kind of government it is who has never been in prison. — Leo Tolstoy

Leve fit, quod bene fertur onus. (A burden becomes lightest when it is well borne.)

To secure ourselves against defeat lies in our own hands, but the opportunity of defeating the enemy is provided by the enemy himself. — Sun Tzu

Verba volant, scripta manent. (The spoken word flees; the written word remains.) — Ancient Roman adage

(Peter Ustinov explains why he reads so much:) “If you’re going to be the prisoner of your own mind, the least you can do is to make sure it’s well furnished.”

To be without some of the things you want is an indispensable part of happiness. — Bertrand Russell

Altogether “Kathy” compiled seven notebooks over 26 years, drawing not just on his study materials and smuggled newspapers but on 5,000 books donated to the prison library by a Cape Town bookstore. Finally released in 1989, he went on to become a member of Parliament after South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994 and served as President Nelson Mandela’s parliamentary counsellor until 1999.

One of his former warders, Christo Brand, told him, “I was supposed to be your master, but instead you became my mentor.”

(Sahm Venter, ed., Ahmed Kathrada’s Notebook From Robben Island, 2005.)