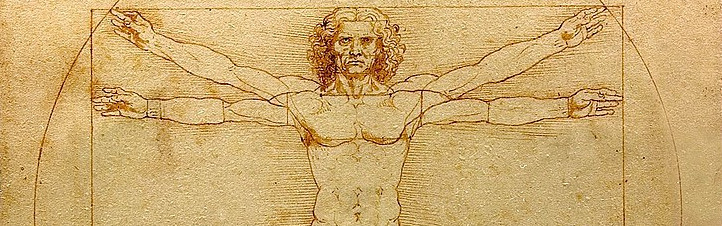

Aristotle referred to humans as the “state-building animal.” Other names our species has proposed for itself, in various writings:

Homo absconditus: “man the inscrutable”

Homo adorans: “worshipping man”

Homo aestheticus: “aesthetic man”

Homo amans: “loving man”

Homo animalis: “man with a soul”

Homo avarus: “man the greedy”

Homo creator: “creator man”

Homo demens: “mad man” (the only creature with irrational delusions)

Homo discens: “learning man”

Homo domesticus: “domestic man” (because he builds his environment)

Homo duplex: “double man” (because of his animal and social tendencies)

Homo economicus: “economic man”

Homo educandus: “to be educated” (we require education to reach maturity)

Homo ethicus: “ethical man”

Homo excentricus: “not self-centered” (we’re capable of objectivity and self-reflection)

Homo faber: “toolmaker man”

Homo ferox: “ferocious man” (T.H. White)

Homo grammaticus: “grammatical man”

Homo humanus: “human man” (as opposed to Homo biologicus)

Homo hypocritus: “hypocritical man” (Robin Hanson, who also called us “man the sly rule bender”)

Homo imitans: “imitating man” (capable of learning by imitation)

Homo inermis: “helpless man” (devoid of animal instincts)

Homo investigans: “investigating man” (curious and capable of learning by deduction)

Homo laborans: “working man” (capable of dividing labor and specializing)

Homo logicus: “the man who wants to understand”

Homo loquens: “talking man”

Homo loquax: “chattering man” (Henri Bergson)

Homo ludens: “playing man” (Schiller)

Homo mendax: “lying man” (able to tell lies)

Homo metaphysicus: “metaphysical man” (Schopenhauer)

Pan narrans: “storytelling ape” (Terry Pratchett)

Homo necans: “killing man”

Homo patiens: “suffering man” (Viktor Frankl)

Homo pictor: “depicting man”

Homo poetica: “man the poet”

Homo religiosus: “religious man”

Homo ridens: “laughing man”

Homo reciprocans: “reciprocal man” (a cooperative actor)

Homo sanguinis: “bloody man”

Homo sciens: “knowing man”

Homo sentimentalis: “sentimental man” (empathizing and idealizing emotions)

Homo socius: “social man”

Homo sociologicus: “sociological man” (prone to sociology)

Homo technologicus: “technological man”

Homo viator: “man the pilgrim” (on his way toward finding God)

Wikipedia lists 72 of these. Douglas Adams wrote, “Human beings, who are almost unique in having the ability to learn from the experience of others, are also remarkable for their apparent disinclination to do so.”