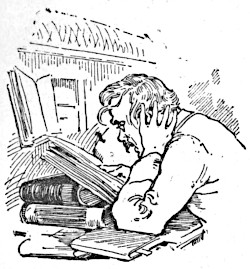

In Three Men in a Boat (1889), the narrator reads a medical textbook and is stricken with the certainty that he has every condition described there:

I came to typhoid fever — read the symptoms — discovered that I had typhoid fever, must have had it for months without knowing it — wondered what else I had got; turned up St. Vitus’s Dance — found, as I expected, that I had that too … I plodded conscientiously through the twenty-six letters, and the only malady I could conclude I had not got was housemaid’s knee.

This is a recognized phenomenon. In 1908, Boston neurologist George Lincoln Walton reported:

Medical instructors are continually consulted by students who fear that they have the diseases they are studying. The knowledge that pneumonia produces pain in a certain spot leads to a concentration of attention upon that region which causes any sensation there to give alarm. The mere knowledge of the location of the appendix transforms the most harmless sensations in that region into symptoms of serious menace.

In 2004 University of Toronto psychiatrist Brian Hodges noted that “medical students’ disease” is said to afflict 70 to 80 percent of students, often invading their dreams. Walton wrote, “The sensible student learns to quiet these fears, but the victim of ‘hypos’ returns again and again for examination, and perhaps finally reaches the point of imparting, instead of obtaining, information, like the patient in a recent anecdote from the Youth’s Companion:”

It seems that a man who was constantly changing physicians at last called in a young doctor who was just beginning his practice.

‘I lose my breath when I climb a hill or a steep flight of stairs,’ said the patient. ‘If I hurry, I often get a sharp pain in my side. Those are the symptoms of a serious heart trouble.’

‘Not necessarily, sir,’ began the physician, but he was interrupted.

‘I beg your pardon!’ said the patient irritably. ‘It isn’t for a young physician like you to disagree with an old and experienced invalid like me, sir!’