-20 = -20

25 – 45 = 16 – 36

52 – 45 = 42 – 36

52 – 45 + 81/4 = 42 – 36 + 81/4

(5 – 9/2)2 = (4 – 9/2)2

5 – 9/2 = 4 – 9/2

5 = 4

We already know that 1 = 0, that 2 = 1 and that one dollar equals one cent. Does this mean that money has no value?

-20 = -20

25 – 45 = 16 – 36

52 – 45 = 42 – 36

52 – 45 + 81/4 = 42 – 36 + 81/4

(5 – 9/2)2 = (4 – 9/2)2

5 – 9/2 = 4 – 9/2

5 = 4

We already know that 1 = 0, that 2 = 1 and that one dollar equals one cent. Does this mean that money has no value?

Dr. Price, in the second edition of his “Observations on Reversionary Payments,” says: “It is well known to what prodigious sums money improved for some time at compound interest will increase. A penny so improved from our Saviour’s birth, as to double itself every fourteen years — or, what is nearly the same, put out at five per cent. compound interest at our Saviour’s birth — would by this time have increased to more money than could be contained in 150 millions of globes, each equal to the earth in magnitude, and all solid gold. A shilling, put out at six per cent. compound interest would, in the same time, have increased to a greater sum in gold than the whole solar system could hold, supposing it a sphere equal in diameter to the diameter of Saturn’s orbit. And the earth is to such a sphere as half a square foot, or a quarto page, to the whole surface of the earth.”

— Barkham Burroughs’ Encyclopaedia of Astounding Facts and Useful Information, 1889

Account of an encounter with a titanic shark, recorded by Australian naturalist David Stead in his 1963 book Sharks and Rays of Australian Seas:

In the year 1918 I recorded the sensation that had been caused among the “outside” crayfish men at Port Stephens, when, for several days, they refused to go to sea to their regular fishing grounds in the vicinity of Broughton Island. The men had been at work on the fishing grounds — which lie in deep water — when an immense shark of almost unbelievable proportions put in an appearance, lifting pot after pot containing many crayfishes, and taking, as the men said, “pots, mooring lines and all”. These crayfish pots, it should be mentioned, were about 3 feet 6 inches in diameter and frequently contained from two to three dozen good-sized crayfish each weighing several pounds. The men were all unanimous that this shark was something the like of which they had never dreamed of. In company with the local Fisheries Inspector I questioned many of the men very closely and they all agreed as to the gigantic stature of the beast. But the lengths they gave were, on the whole, absurd. I mention them, however, as an indication of the state of mind which this unusual giant had thrown them into. And bear in mind that these were men who were used to the sea and all sorts of weather, and all sorts of sharks as well. One of the crew said the shark was “three hundred feet long at least”! Others said it was as long as the wharf on which we stood — about 115 feet! They affirmed that the water “boiled” over a large space when the fish swam past. They were all familiar with whales, which they had often seen passing at sea, but this was a vast shark. They had seen its terrible head which was “at least as long as the roof on the wharf shed at Nelson Bay.” Impossible, of course! But these were prosaic and rather stolid men, not given to “fish stories” nor even to talking about their catches. Further, they knew that the person they were talking to (myself) had heard all the fish stories years before! One of the things that impressed me was that they all agreed as to the ghostly whitish colour of the vast fish.

Stead draws no conclusions, but writes, “The local Fisheries Inspector of the time, Mr Paton, agreed with me that it must have been something really gigantic to put these experienced men into such a state of fear and panic.”

epicaricacy

n. taking pleasure in others’ misfortune

Only two U.S. state names can be typed with a single hand on a normal keyboard. What are they?

New York City as seen from space, Sept. 11, 2001.

The average age of the city’s dead was 40.

Born without arms, Frances O’Connor (1914-1982) was billed as a living Venus de Milo in popular sideshows, eating, drinking, and smoking a cigarette with her feet.

See also Carl Herman Unthan.

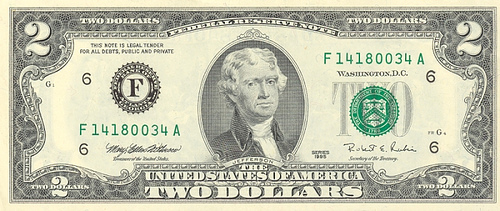

As a prank, Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak sometimes buys uncut sheets of $2 bills from the U.S. Treasury and has them bound into booklets. Then, when buying small items, he’ll pull out a booklet and cut off a few bills with scissors.

This is perfectly legal, but it’s caused at least one alarmed inquiry by the Secret Service.

The square dance is the official dance of 19 U.S. states.

Text of an ancient Macedonian scroll discovered in Greece in 1986:

On the formal wedding of [Theti]ma and Dionysophon I write a curse, and of all other wo[men], widows and virgins, but of Thetima in particular, and I entrust upon Makron and [the] demons that only whenever I dig out and unroll and re-read this, [then] may they wed Dionysophon, but not before; and may he never wed any woman but me; and may [I] grow old with Dionysophon, and no one else. I [am] your supplicant: Have mercy on [your dear one], dear demons, Dagina(?), for I am abandoned of all my dear ones. But please keep this for my sake so that these events do not happen and wretched Thetima perishes miserably and to me grant [ha]ppiness and bliss.

It would have been written in the 4th or 3rd century B.C.