Here are three cups, one upside down.

Turning over exactly two cups with each move, can you turn all cups right-side-up in no more than six moves?

If it’s possible, show how; if it’s not, say why.

Here are three cups, one upside down.

Turning over exactly two cups with each move, can you turn all cups right-side-up in no more than six moves?

If it’s possible, show how; if it’s not, say why.

The late Mr. Dawson Damer — ‘Hippy’ Damer, afterwards Lord Portarlington — was one of the most deservedly popular men in London and a great favourite of Queen Victoria. The Prince of Wales gave a garden party at Marlborough House to his mother, and to this gathering ‘Hippy’ Damer came — but came very much under the influence of ‘la dive bouteille.’ Spying the Queen he went up to her offered his hand cordially and said: ‘Gad! How glad I am to see you! How well you’re looking! But, I say, do forgive me — your face is, of course, very familiar to me; but I can’t for the life of me recall your name!’ The Queen took in the situation at once, and as she cordially grasped the hand extended to her, said smiling: ‘Oh, never mind my name, Mr. Damer — I’m very glad to see you. Sit down and tell me all about yourself.’

— Julian Osgood Field, Uncensored Recollections, 1924

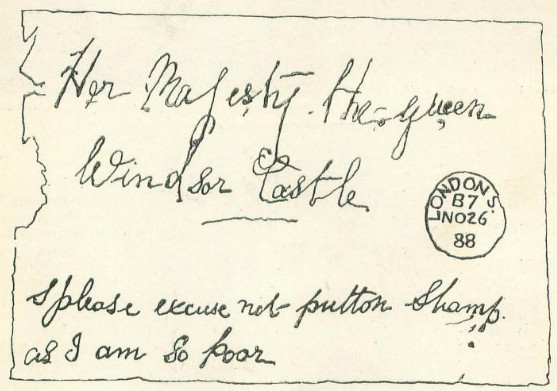

Below: “Her Majesty has been the recipient of some remarkably addressed envelopes,” reported the Strand in 1891.

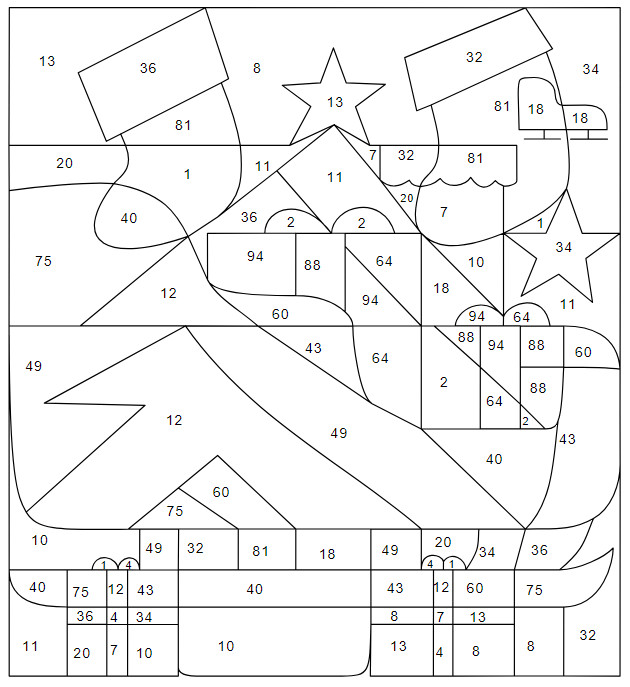

Mathematician Matthew Scroggs has released this year’s Christmas card for Chalkdust magazine.

Solve 10 mathematical puzzles and the answers will guide you in coloring the picture.

O for a muse of fire, a sack of dough,

Or both! O promissory notes of woe!

One time in Santa Fe N.M.

Ol’ Winfield Townley Scott and I … But whoa.

One can exert oneself, ff,

Or architect a heaven like Rimbaud,

Or if that seems, how shall I say, de trop,

One can at least write sonnets, a propos

Of nothing save the do-re-mi-fa-sol

Of poetry itself. Is not the row

Of perfect rhymes, the terminal bon mot,

Obeisance enough to the Great O?

“Observe,” said Chairman Mao to Premier Chou,

“On voyage à Parnasse pour prendre les eaux.

On voyage comme poisson, incog.”

— George Starbuck

Diagnosed with terminal melanoma at 50, Phoebe Snetsinger resolved to devote her remaining time to watching birds. Between 1981 and 1999, as her cancer went periodically into remission, she visited every continent several times over, traversing jungles, swamps, deserts, and mountains and surviving malaria, a boat accident, abduction in Ethiopia, and rape in Papua New Guinea. In 1995 she became the first person to see 8,000 species of bird, and in time she extended the list to 8,398, nearly 85 percent of the world’s known species. She died in 1999 when her van overturned during a birding trip in Madagascar. The last bird she’d observed was a red-shouldered vanga, a species that had been described as new to science only two years previously.

In her memoir, Birding on Borrowed Time, she wrote, “When I was given my death sentence by the doctors, one of my immediate reactions that I clearly remember was ‘Oh no — there are all those things I haven’t yet done, and now will never have a chance to do.’ … The preparation and primarily the birding itself, plus the record keeping afterwards, all enabled me to forget the threat to my life (or at least push it aside) and to immerse myself totally in what I was doing.”

Arthur Conan Doyle tells us little about James Moriarty, the criminal mastermind in the Sherlock Holmes stories. But he does mention one intriguing accomplishment in The Valley of Fear:

Is he not the celebrated author of The Dynamics of an Asteroid, a book which ascends to such rarefied heights of pure mathematics that it is said that there was no man in the scientific press capable of criticizing it?

Mathematicians Alain Goriely and Simon P. Norton have both pointed out that in 1887 King Oscar II of Sweden offered a bounty for the solution to the n-body problem in celestial mechanics. Doyle’s story was set in 1888, so it’s possible that Moriarty had intended his book as his entry in this contest.

If he did, he was disappointed — the prize went to Henri Poincaré.

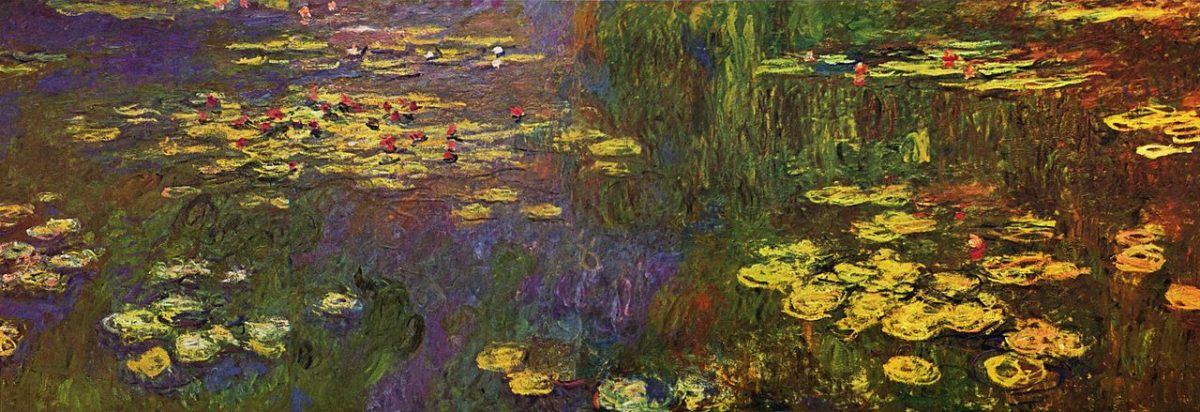

“Poetry is not the thing said but a way of saying it.” — G.H. Hardy

“The representative element in a work of art may or may not be harmful; always it is irrelevant.” — Clive Bell

From reader Snehal Shekatkar:

There exist exactly 17 numbers the sum of whose distinct prime factors is exactly 17:

17 = 17

52 = 2 × 2 × 13

88 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 11

99 = 3 × 3 × 11

147 = 3 × 7 × 7

175 = 5 × 5 × 7

210 = 2 × 3 × 5 × 7

224 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 7

250 = 2 × 5 × 5 × 5

252 = 2 × 2 × 3 × 3 × 7

300 = 2 × 2 × 3 × 5 × 5

320 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 ×2 × 2 × 5

360 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 3 × 3 × 5

384 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 3

405 = 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 × 5

432 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 3 × 3 × 3

486 = 2 × 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 × 3

(Thanks, Snehal.)

A puzzle from Henry Dudeney’s Modern Puzzles and How to Solve Them, 1926:

This is a rough sketch of the finish of a race up a staircase in which three men took part. Ackworth, who is leading, went up three risers at a time, as arranged; Barnden, the second man, went four risers at a time, and Croft, who is last, went five at a time.

Undoubtedly Ackworth wins. But the point is, How many risers are there in the stairs, counting the top landing as a riser?

I have only shown the top of the stairs. There may be scores, or hundreds, of risers below the line. It was not necessary to draw them, as I only wanted to show the finish. But it is possible to tell from the evidence the fewest possible risers in that staircase. Can you do it?

There is a distinct difference between ‘suspense’ and ‘surprise,’ and yet many pictures continually confuse the two. I’ll explain what I mean. We are now having a very innocent little chat. Let’s suppose that there is a bomb underneath this table between us. Nothing happens, and then all of a sudden, ‘Boom!’ There is an explosion. The public is surprised, but prior to this surprise, it has seen an absolutely ordinary scene, of no special consequence. Now, let us take a suspense situation. The bomb is underneath the table and the public knows it, probably because they have seen the anarchists place it there. The public is aware the bomb is going to explode at one o’clock and there is a clock in the decor. The public can see that it is a quarter to one. In these conditions, the same innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene. The audience is longing to warn the characters on the screen: ‘You shouldn’t be talking about such trivial matters. There is a bomb beneath you and it is about to explode!’ In the first case, we have given the public fifteen seconds of surprise at the moment of the explosion. In the second we have provided them with fifteen minutes of suspense. The conclusion is that whenever possible the public must be informed. Except when the surprise is a twist, that is, when the unexpected ending is, in itself, the highlight of the story.

(Via François Truffaut’s Hitchcock, 1967.)