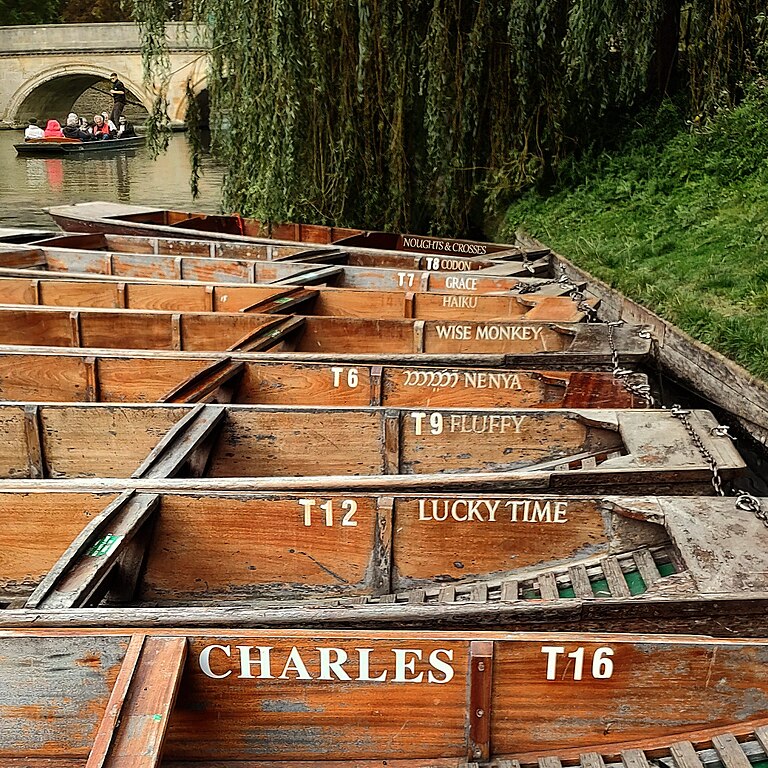

These are the punts of Trinity College, Cambridge, moored on the River Cam. What is the significance of their names?

These are the punts of Trinity College, Cambridge, moored on the River Cam. What is the significance of their names?

Steaming from New York to the Azores in 1867, Mark Twain noted a curious companion overhead:

We had the phenomenon of a full moon located just in the same spot in the heavens at the same hour every night. The reason of this singular conduct on the part of the moon did not occur to us at first, but it did afterward when we reflected that we were gaining about twenty minutes every day because we were going east so fast — we gained just about enough every day to keep along with the moon. It was becoming an old moon to the friends we had left behind us, but to us Joshuas it stood still in the same place and remained always the same.

(From The Innocents Abroad.)

02/11/2025 Reader Catalin Voinescu writes:

Mark Twain is talking absolute nonsense here.

The moon is in (almost) the same phase as seen from all over the world. It rises and sets at roughly the same local time, regardless of longitude, and the relation between phase and time of day when the moon is visible is the same everywhere (the full moon peaks at midnight; a week later, the last-quarter moon rises around midnight, peaks in the morning and sets around noon; and so on).

Even ignoring moon phase and local time, the moon rises, peaks and sets almost 50 minutes later every day, so gaining 20 minutes every day would not be enough.

(Thanks, Catalin.)

Reader J. William Hook submitted this curiosity to the Strand in August 1899. Holding the page level with the eyes foreshortens the characters and reveals a love poem:

Art thou not dear unto my heart?

Oh, I search that heart and see

And from my bosom tear the part

That beats not true to thee.

But to my bosom thou art dear,

More dear than words can tell,

And if a fault be cherished there,

‘Tis loving thee too well.

There seems to have been a little vogue for this kind of thing — C. Field submitted a similar image three months later.

(Until William Herschel’s advances in telescopes, stars seemed to have “rays” or “tails.”)

At a dinner given by Mr Aubert in the year 1786, William Herschel was seated next to Mr Cavendish, who was reputed to be the most taciturn of men. Some time passed without his uttering a word, then he suddenly turned to his neighbour and said: ‘I am told that you see the stars round, Dr Herschel’. ‘Round as a button’, was the reply. A long silence ensued till, towards the end of the dinner, Cavendish again opened his lips to say in a doubtful voice: ‘Round as a button?’ ‘Exactly, round as a button’, repeated Herschel, and so the conversation ended.

— Constange A. Lubbock, The Herschel Chronicle, 1933

An art gallery with n walls will always be safe with n/3 guards — the guards will always be able arrange themselves to observe the whole gallery.

That’s Chvátal’s art gallery theorem, discovered in 1973 by mathematician Václav Chvátal. Interestingly, it’s true only of two-dimensional floor plans — a three-dimensional gallery may not be safe even if you post a guard at every corner.

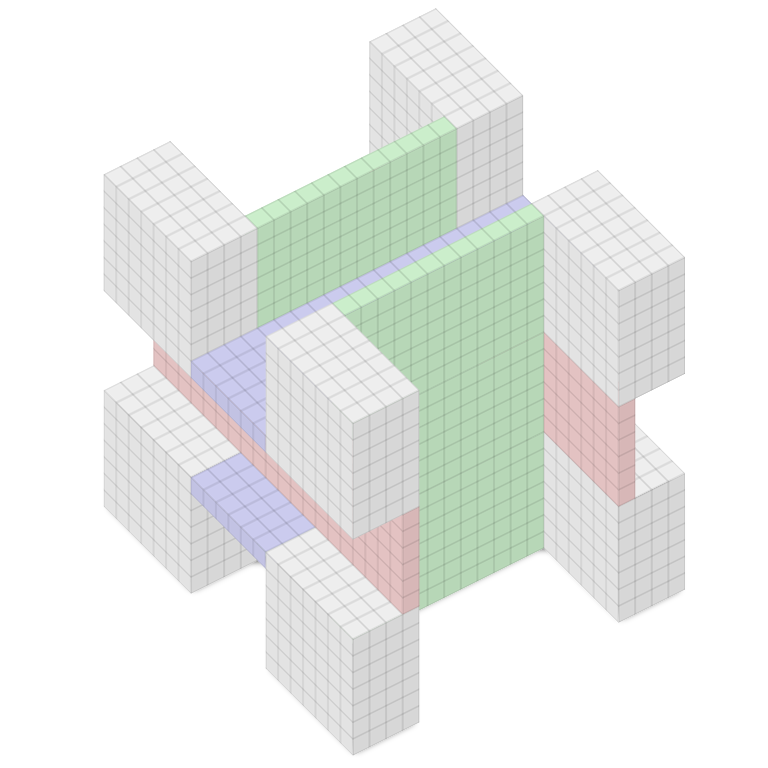

Take a 20 × 20 × 20 cube and remove a 12 × 6 channel from the front and back faces; a 6 × 3 channel from the left and right faces; and a 6 × 6 channel from the top and bottom faces, as shown. The result is the Octoplex, eight 4 × 7 × 7 theaters connected to each other and to a central lobby by passages 1 unit wide.

Remarkably, even if we mount a camera at every one of this figure’s 56 corners, there will remain a small region in the central lobby that no camera can see.

(T.S. Michael, “Guards, Galleries, Fortresses, and the Octoplex,” College Mathematics Journal 42:3 [May 2011], 191-200.)

For the past eighty years I have started each day in the same manner. It is not a mechanical routine but something essential to my daily life. I go to the piano, and I play two preludes and fugues of Bach. I cannot think of doing otherwise. It is a sort of benediction on the house. But that is not its only meaning for me. It is a rediscovery of the world of which I have the joy of being a part. It fills me with awareness of the wonder of life, with a feeling of the incredible marvel of being a human being.

— Pablo Casals, Joys and Sorrows, 1970

renitence

n. unwillingness, resistance to persuasion

subdolous

adj. cunning, crafty, sly

autoschediasm

n. something done on the spur of the moment or without preparation

legerity

n. physical or mental quickness

FDR’s secretary of state, Cordell Hull, was famously unforthcoming, concealing his plans and emotions with the skill of a poker player.

When Hull was a legislator in Tennessee, one of his friends bet that he could get a direct answer out of him. He stopped him in the capitol and asked him the time.

Hull took out his timepiece, looked at it, and said, “What does your watch say?”

From Martin Geldart’s Guide to Modern Greek, 1883:

Here we are (arrived) at the station.

What luggage have you, sir?

I have two trunks, a travelling-bag, and a hat-box, for the luggage van.

These I wish to register.

My other luggage I will take with me.

That is to say — a foot-wrapper, a stick, three or four parcels, a gun, a lap-dog, two Turkish pipes, and a live tortoise.

As for the rest, let them pass; but for the dog a separate ticket must be taken, and he must go in the van.

As for the tortoise, you must leave that behind: we don’t convey vermin!

Vermin! So you reckon a tortoise among the vermin?

Certainly, sir; it’s an insect.

An insect! My good fellow, where did you go to school (study)?

I refer you to the Zoological Garden(s), and there you will learn, if you have any brains in your head, that the tortoise is a four-footed reptile, and that insects are all six-footed.

There’s a shilling for you, the price of admission to the Zoological Gardens, except on Mondays, when it is only sixpence.

If you have time on Mondays, go twice, that you may be more thoroughly enlightened.

Oh, that alters the question, sir! And, now I come to think of it, the landlord over the way has a book with those kind of creatures in it. I daresay you’re right (lit. Let be then). All the same, four-foot and six-foot have another meaning in my business.

All the better! Mind your own business then, and leave the four-footed reptiles to me.

In September 1931 the Weekend Review pointed out the “regrettable omission of any reference to tooth-brushing in the description of Adam and Eve retiring for the night” in Book IV of Paradise Lost. It challenged its readers to improve Milton’s text; polymath Edward Marsh inserted these lines:

[… and eas’d the putting off

These troublesome disguises which wee wear,]

Yet pretermitted not the strait Command,

Eternal, indispensable, to off-cleanse

From their white elephantin Teeth the stains

Left by those tastie Pulps that late they chewd

At supper. First from a salubrious Fount

Our general Mother, stooping, the pure Lymph

Insorb’d, which, mingl’d with tart juices prest

From pungent Herbs, on sprigs of Myrtle smeard,

(Then were not Brushes) scrub’d gumms more impearl’d

Than when young Telephus with Lydia strove

In mutual bite of Shoulder and ruddy Lip.

This done (by Adam too no less) the pair

[Straight side by side were laid …]

Marsh called this “the cleverest thing I ever did.” “The mordacious Telephus and Lydia are ‘of course,’ as the gossip-writers would say, from Horace, Odes, I, xiii. Martin Armstrong, who had set the competition, gave me the first prize, and was good enough to express the hope that future editors of Milton would put my lines in the appropriate place.”

(From Marsh’s 1939 memoir A Number of People.)