Benjamin Franklin’s “13 virtues,” which he devised for “the bold and arduous project of arriving at moral perfection”:

- TEMPERANCE. Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation.

- SILENCE. Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself; avoid trifling conversation.

- ORDER. Let all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time.

- RESOLUTION. Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve.

- FRUGALITY. Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i.e., waste nothing.

- INDUSTRY. Lose no time; be always employ’d in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions.

- SINCERITY. Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly, and, if you speak, speak accordingly.

- JUSTICE. Wrong none by doing injuries, or omitting the benefits that are your duty.

- MODERATION. Avoid extreams; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve.

- CLEANLINESS. Tolerate no uncleanliness in body, cloaths, or habitation.

- TRANQUILLITY. Be not disturbed at trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable.

- CHASTITY. Rarely use venery but for health or offspring, never to dulness, weakness, or the injury of your own or another’s peace or reputation.

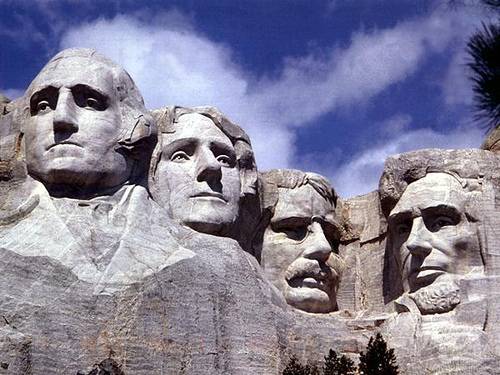

- HUMILITY. Imitate Jesus and Socrates.

“It may be well my posterity should be informed that to this little artifice, with the blessing of God, their ancestor ow’d the constant felicity of his life, down to his 79th year, in which this is written.”