I am greater than God, and more evil than the devil. Poor people have me. Rich people want me. And if you eat me, you’ll die. What am I?

Progress Marches On

Uncle Billy rested his axe on the log he was chopping, and turned his grizzly old head to one side, listening intently. A confusion of sounds came from the little cabin across the road. It was a dilapidated negro cabin, with its roof awry and the weather-boarding off in great patches; still, it was a place of interest to Uncle Billy. His sister lived there with three orphan grandchildren.

Leaning heavily on his axe-handle, he thrust out his under lip, and rolled his eyes in the direction of the uproar. A broad grin spread over his wrinkled black face as he heard the rapid spank of a shingle, the scolding tones of an angry voice, and a prolonged howl.

“John Jay an’ he gran’mammy ‘peah to be havin’ a right sma’t difference of opinion togethah this mawnin’,” he chuckled.

— Annie Fellows Johnston, Ole Mammy’s Torment, 1897

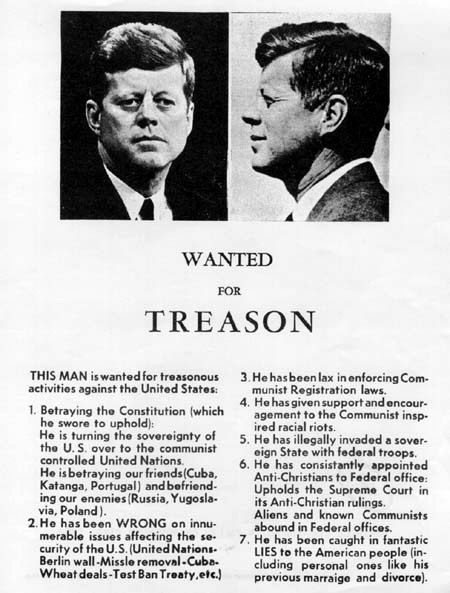

JFK Wanted

Handbill circulated in Dallas on Nov. 21, 1963, the day before Kennedy’s assassination:

Trick or Treat

In October 1998, 300 dead starlings fell out of the sky in Tacoma, Wash.

No one knows why.

Revenge of the Food Chain

A human sacrifice to a carnivorous tree, as described in the South Australian Register, 1881:

The slender delicate palpi, with the fury of starved serpents, quivered a moment over her head, then as if instinct with demoniac intelligence fastened upon her in sudden coils round and round her neck and arms; then while her awful screams and yet more awful laughter rose wildly to be instantly strangled down again into a gurgling moan, the tendrils one after another, like great green serpents, with brutal energy and infernal rapidity, rose, retracted themselves, and wrapped her about in fold after fold, ever tightening with cruel swiftness and savage tenacity of anacondas fastening upon their prey.

Unfortunately, years of subsequent investigation — including the enchantingly titled Madagascar, Land of the Man-Eating Tree (1924) — have failed to find such a tree, or even the Mkodo tribe that purportedly feeds it. Nice try, though.

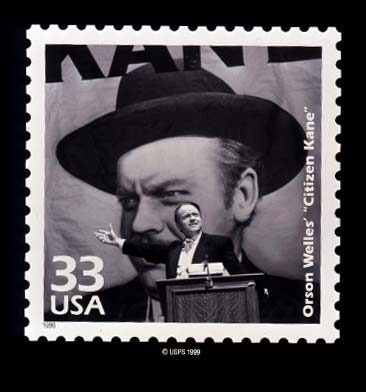

“Rosebud”

After viewing Citizen Kane, a friend asked Orson Welles how anyone could know Kane’s last words when he died alone.

Reportedly Welles stared for a long time and said, “Don’t you ever tell anyone of this.”

Unquote

“Had I been present at the Creation, I would have given some useful hints for the better ordering of the universe.” — Alfonso, king of Castile (1221-1284), on studying the Ptolemaic system

Pneumonia Victims

Famous people who died of pneumonia:

- William Henry Harrison

- Leo Tolstoy

- Jim Backus

- Lawrence Welk

- Billy Wilder

- Charles Bronson

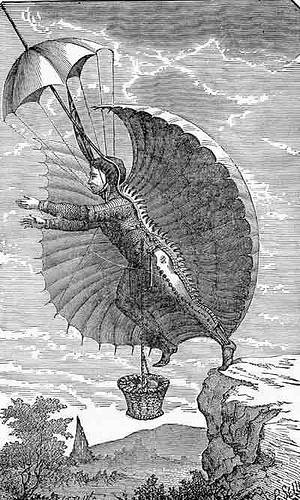

“Up in the Air”

“This gentleman had an idea that he could fly by the aid of this ingenious machinery. You will see that his wings are arranged so that they are moved by his legs, and also by cords attached to his arms. The umbrella over his head is not intended to ward off the rain or the sun, but is to act as a sort of parachute, to keep him from falling while he is making his strokes. The basket, which hangs down low enough to be out of the way of his feet, is filled with provisions, which he expects to need in the course of his journey.

“That journey lasted exactly as long as it took him to fall from the top of a high rock to the ground below.”

— Frank R. Stockton, Round-About Rambles in Lands of Fact and Fancy, 1910

Rat Kings

Every so often someone finds a bunch of rats whose tails are knotted together. It’s called a rat king. (This one, with 32 rats, was found in a German miller’s fireplace in 1828.)

The rats are usually dead when they’re discovered, and no one has suggested a natural cause, so presumably humans are involved somehow.

Typically the rats are fully grown adults, so they’re not born this way, and their tails are often broken and callused, which means they’ve survived in this state for some time, fed by humans or by other rats.

Why would anyone do this? Who knows?