DIY

In 1962, determined to start life anew, Yorkshire newspaper editor Brendon Grimshaw purchased little Moyenne Island in the Seychelles for £8,000. He remained there for the next 40 years. In that time Grimshaw and an assistant planted 16,000 trees by hand, built three miles of nature paths, attracted 2,000 new birds, and became caretakers of 120 giant tortoises. The island now hosts two thirds of all plants endemic to the Seychelles.

Grimshaw once turned down an offer of $50 million for the island, saying that he didn’t want to see it become a holiday destination for millionaires. Instead, in 2008 it was named a national park. Grimshaw died in 2012, but today a warden is posted on the island to collect entrance fees from tourists.

How Many Swaps?

From reader Éric Angelini:

Call this S1:

FIRST, SECOND, THIRD, FOURTH, FIFTH, SIXTH, SEVENTH, EIGHTH, NINTH, TENTH, ELEVENTH, …

Consider it both a string of letters and a list of instructions: We are to underline the indicated letters, in order. That’s pretty straightforward — we’ll underline the first letter, then the second, then the third, and so on, ultimately reproducing S1.

Suppose we start the list with SIXTH, rather than FIRST. Now our first instruction is to underline the sixth letter, which is the S in SECOND. After that we underline the second letter in the string, as before, and the third, and so on. Only the very first letter, the F in FIRST, has been overlooked, and we can remedy that by putting FIRST in the sixth position in the list. With that swap all is well:

S6 = SIXTH, SECOND, THIRD, FOURTH, FIFTH, FIRST, SEVENTH, EIGHTH, NINTH, TENTH, ELEVENTH, …

Similarly, if the list starts with EIGHTH we can get everything underlined with just a single swap:

S8 = EIGHTH, SECOND, THIRD, FOURTH, FIFTH, SIXTH, SEVENTH, FIRST, NINTH, TENTH, ELEVENTH, …

Éric asks, “What about starting S9 with NINTH? How many swaps do we need to reproduce S9? This is more tricky!”

See the answer by Hans Havermann at the bottom of this page.

(Thanks, Éric.)

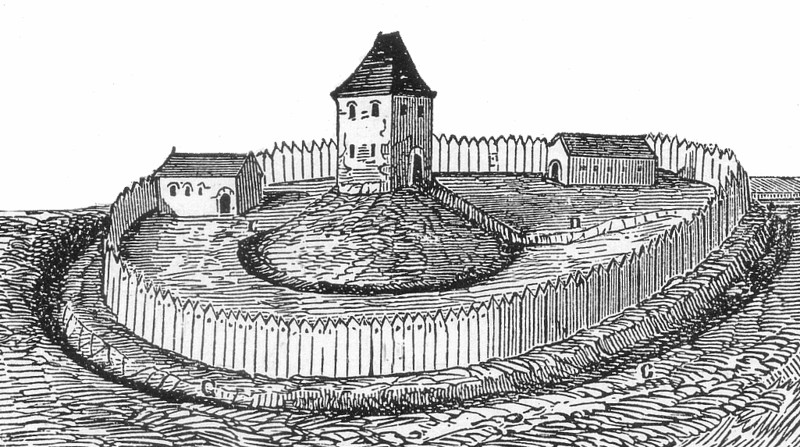

The Motte-and-Bailey Fallacy

In 2005, philosopher Nicholas Shackel identified a form of argument in which an arguer claims to defend a controversial position while retreating, under pressure, to a more supportable one. He likened it to a medieval castle defense known as the motte and bailey, in which a stone tower, the motte, is surrounded by an area of open land, the bailey. If maurauders invade the bailey, the defender retreats to the motte, and when the attackers have given up he can reoccupy the bailey.

“For my purposes the desirable but only lightly defensible territory of the Motte and Bailey castle, that is to say, the Bailey, represents a philosophical doctrine or position with similar properties: desirable to its proponent but only lightly defensible,” Shackel wrote. “The Motte is the defensible but undesired position to which one retreats when hard pressed.”

By withdrawing as needed to a better-supported claim, a skilled arguer can pretend greater security than he’s established, and even accuse his critics of misrepresenting his position. Other writers have suggested that this is a common tactic in pseudoscience.

(Nicholas Shackel, “The Vacuity of Postmodernist Methodology,” Metaphilosophy 36:3 [April 2005], 295–320.)

Keith Numbers

The number 197 has a curious property:

1 + 9 + 7 = 17

9 + 7 + 17 = 33

7 + 17 + 33 = 57

17 + 33 + 57 = 107

33 + 57 + 107 = 197

After its n digits are used to initiate this pattern, the seeding number itself turns up in the resulting sequence. This makes 197 a Keith number, named for Mike Keith, the mathematician who first remarked on this property in 1987.

Keith numbers are rare and discovered only through exhaustive search, and progress stopped for 13 years after D. Lichtblau found the 34-digit 5752090994058710841670361653731519 in August 2009. But last December, while compiling a programming assignment, Ghent University mathematician Toon Baeyens found all the 35- and 36-digit Keith numbers:

23137274755282109912063039769168142

25314398891465125143523864790391288

44715370344837755402179510861188022

47933465320021485928519060435917729

196866601633638871239614307772203156

214860400509971669129437189647933258

394684240118372710589383926683340073

763701584467955209221750616718219223

880430656963418264331749765271577784

That last entry is now the largest Keith number known.

(Thanks, Peter.)

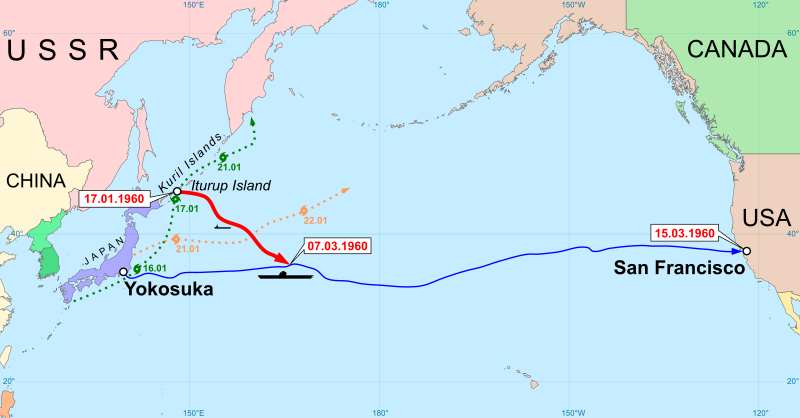

Adrift

Fighting a storm in the Kuril Archipelago in January 1960, Soviet barge T-36 ran out of fuel and was carried out of its lagoon and into the open ocean. By the time the storm ceased it had also lost its radio transmitter, and when rescue crews found debris it was concluded that the vessel had sunk.

In fact it was drifting eastward across the North Pacific. The barge had recently been stocked with a three days’ supply of food and water, but some of this had been ruined in the storm, and the four-man crew were eventually reduced to eating their shoes and belts as they drifted endlessly east. “Each time we awoke, we were surprised to be alive,” private Philip Poplavski later told Time. “But we felt we were too young to die.”

Finally, after 49 days, they were spotted by an American Navy reconnaissance plane and picked up by the aircraft carrier Kearsarge. Amid worldwide publicity, the crew sailed to Paris on the Queen Mary, then flew back to the Soviet Union.

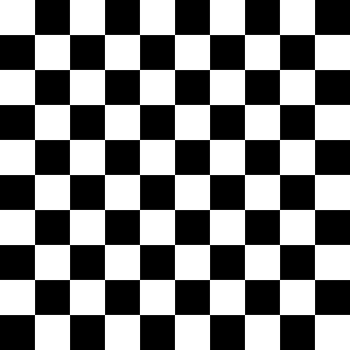

Cutup

A problem by Russian mathematician Viktor Prasolov: Prove that it’s impossible to cut a 10×10 chessboard into T-shaped tiles of 4 squares each.

Optical Illusions: Rings

A digital animation by Catherine Leah Palmer.

Profile

A problem from the Stanford University Competitive Examination in Mathematics:

How old is the captain, how many children has he, and how long is his boat? Given the product 32118 of the three desired numbers (integers). The length of the boat is given in feet (is several feet), the captain has both sons and daughters, he has more years than children, but he is not yet one hundred years old.

A Last Performance

Charles Guiteau, James Garfield’s assassin, read a poem at the gallows:

I am going to the Lordy, I am so glad. I am going to the Lordy, I am so glad. I am going to the Lordy, Glory hallelujah! Glory hallelujah! I am going to the Lordy!

I love the Lordy with all my soul, Glory hallelujah! And that is the reason I am going to the Lord. Glory hallelujah! Glory hallelujah! I am going to the Lord.

I saved my party and my land, Glory hallelujah! But they have murdered me for it, and that is the reason I am going to the Lordy. Glory hallelujah! Glory hallelujah! I am going to the Lordy!

I wonder what I will do when I get to the Lordy, I guess that I will weep no more when I get to the Lordy! Glory hallelujah!

I wonder what I will see when I get to the Lordy, I expect to see most splendid things, beyond all earthly conception, when I am with the Lordy! Glory hallelujah! Glory hallelujah! I am with the Lord.

He asked for an orchestral accompaniment, but it was denied.

11/18/2023 UPDATE: Improbably, Guiteau eventually got his accompaniment — in Stephen Sondheim’s 1990 musical Assassins, his character sings part of the poem while cakewalking up and down the scaffold:

(Thanks, Molly.)