Artist François Abelanet created this perspective-based illusion outside the city hall in Paris in 2011. Ninety gardeners worked for five days to prepare an area of 1500 square meters.

Abelanet called it Qui croire? (Who to Believe?).

Artist François Abelanet created this perspective-based illusion outside the city hall in Paris in 2011. Ninety gardeners worked for five days to prepare an area of 1500 square meters.

Abelanet called it Qui croire? (Who to Believe?).

nutation

n. the action of nodding, esp. as a sign of drowsiness

Your beloved daughter is spending the summer at a Japanese monastery. On July 28 you receive a letter from an administrator, dated July 19, saying that she needs to have her wisdom teeth removed. The availability of drugs is not certain: She’ll either have a relatively painful extraction on July 27 or an unpleasant but painless one on July 29. Learning of this situation from afar, which drug would you prefer to have been available?

Now imagine that you receive the letter on July 26 and jet to her bedside. You arrive on July 28 to find her asleep. She seems a little restless, but you don’t know whether that’s because she had a painful extraction yesterday or because she’s anxious about having an unpleasant one tomorrow. Now which do you prefer?

“I find that the large majority of people to whom I present these cases say that they would prefer, in the first case, for their daughter to have the merely unpleasant operation on the 29th, and, in the second case, for their daughter to have had the painful operation on the 27th,” writes MIT philosopher Caspar Hare. “Furthermore, in each case they feel that it makes sense to have the preference, given the way in which it is appropriate to care about a daughter. While they would be loath to condemn a parent with different preferences, they feel that such a parent would be making a kind of mistake.” Why should this be?

(Caspar Hare, “A Puzzle About Other-Directed Time Bias,” Australasian Journal of Philosophy 86:2 [June 2008], 269-277.)

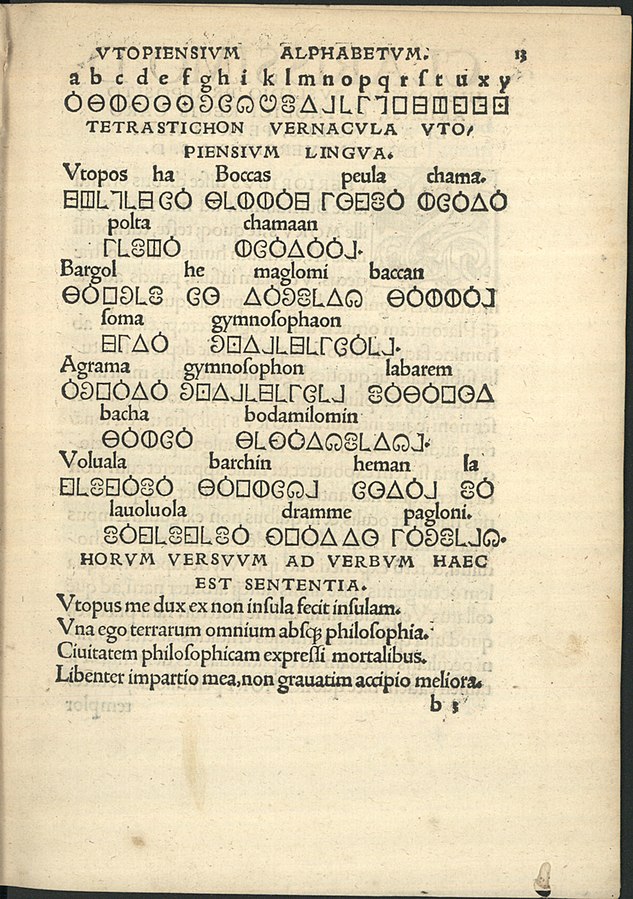

Thomas More’s Utopia gives us not only a description of that imaginary land but the actual alphabet used there: More’s friend Peter Giles wrote an addendum to the book that presents the letters and gives an example of the Utopian writing system:

Vtopos ha Boccas peu la chama polta chamaan.

Bargol he maglomi Baccan foma gymno sophaon.

Agrama gymnosophon labarembacha bodamilomin.

Voluala barchin heman la lauoluola dramme pagloni.

This is translated into Latin as

Utopus me dux ex non insula fecit insulam.

Una ego terrarum omnium absque philosophia

Civitatem philosophicam expressi mortalibus

Libenter impartio mea, non gravatim accipio meliora.

And in English this becomes

The commander Utopus made me into an island out of a non-island.

I alone of all nations, without philosophy,

Have portrayed for mortals the philosophical city.

Freely I impart my benefits; not unwillingly I accept whatever is better.

Working backward, this makes it possible to divine the meaning of a few Utopian words: boccas is commander, chama is island, voluala is willingly, and gymnosophaon is philosophy. You couldn’t really talk about much beyond perfect societies, but maybe that’s the point.

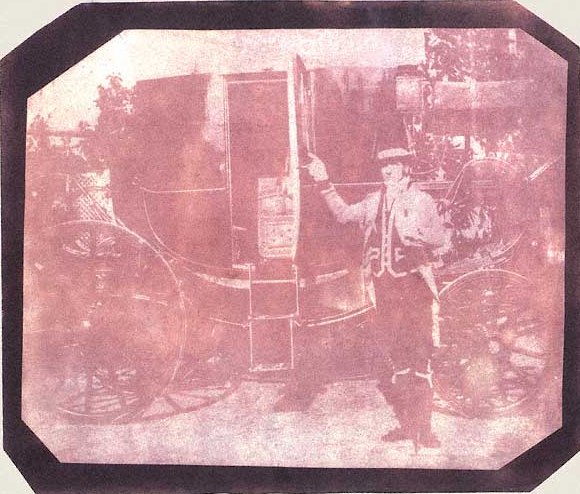

The earliest photograph of a human figure on paper is “The Footman” by William Henry Fox Talbot, from 1840. Footmen came in several varieties; an early breed that quickly went extinct was the running footman, who would advance as a herald before his master’s carriage and also deliver urgent dispatches. In What the Butler Saw, E.S. Turner gives some amazing examples:

“In London the fourth Duke of Queensberry (‘Old Q’) continued to employ running footmen until his death in 1810. He would try out applicants in Piccadilly, lending them his livery for the occasion, and then stand watch in hand on his balcony to time their performance. There is a story that he said to one candidate: ‘You will do very well for me.’ The reply was, ‘And your livery will do very well for me,’ with which the runner bolted.”

Just a charming little anecdote: When German chemist Adolf von Baeyer achieved a long-sought result, he tipped his hat to it:

Eventually, however, even Baeyer was supersaturated with these hydrogenations, and the sorely tried assistants hailed with deep relief the transference of his interest to succinylsuccinic ester and diketocyclohexane. By means of a dodge (‘Kunstgriff’) of which Baeyer was very proud (treatment with sodium amalgam in presence of sodium bicarbonate), the diketone was reduced to quinitol. At the first glimpse of the crystals of the new substance Baeyer ceremoniously raised his hat!

It must be explained here that the Master’s famous greenish-black hat plays the part of a perpetual epithet in Prof. Rupe’s narrative. As the celebrated sword-pommel to Paracelsus, so this romantic hard-hitter or ‘alte Melone’ to Baeyer: the former was said to contain the vital mercury of the mediaeval philosophers; the latter certainly enshrined one of the keenest chemical intellects of the modern world. … Baeyer’s head was normally covered. Only in moments of unusual excitement or elation did the Chef remove his hat: apart from such occasions his shiny pate remained in permanent eclipse.

(From his colleague John Read’s 1947 book Humour and Humanism in Chemistry.)

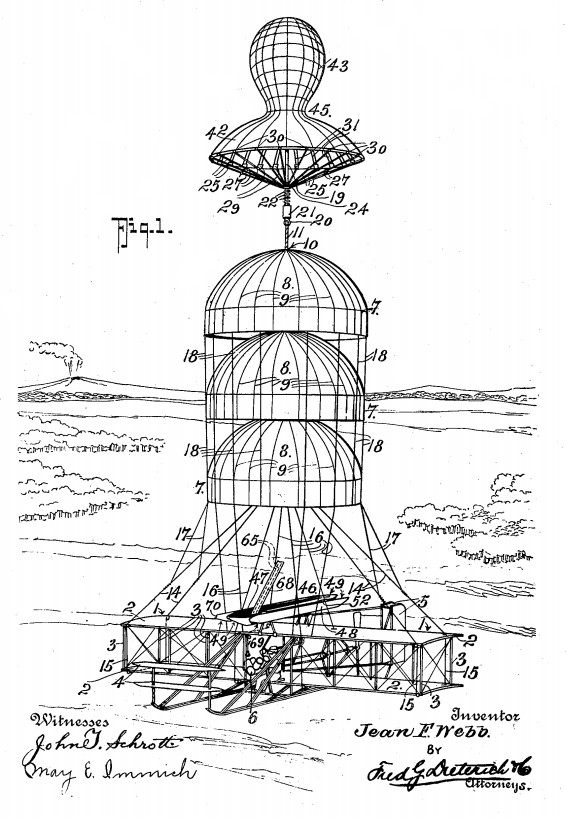

Inventor J.F. Webb proposed this curious safety device in 1910: If your flying machine fails, you release a domelike “air anchor,” which pulls open three parachutes beneath it. These will “sustain the machine sufficiently to break its fall, thereby permitting the machine to descend at a safe speed.”

In The Big Umbrella, his 1973 history of the parachute, John Lucas writes, “Whether Webb’s device worked or not is unknown, but eighteen years later a single parachute 84 feet in diameter and strong enough to support a loaded plane was developed by the U.S. Air Corps.”

“Read, every day, something no one else is reading. Think, every day, something no one else is thinking. Do, every day, something no one else would be silly enough to do. It is bad for the mind to continually be part of unanimity.” — Christopher Morley

For this final episode of the Futility Closet podcast we have eight new lateral thinking puzzles — play along with us as we try to untangle some perplexing situations using yes-or-no questions.

Intro:

Sears used to sell houses by mail.

Many of Lewis Carroll’s characters were suggested by fireplace tiles in his Oxford study.

The sources for this week’s puzzles are below. In some cases we’ve included links to further information — these contain spoilers, so don’t click until you’ve listened to the episode:

Puzzle #1 is from Greg. Here are two links.

Puzzle #2 is from listener Diccon Hyatt, who sent this link.

Puzzle #3 is from listener Derek Christie, who sent this link.

Puzzle #4 is from listener Reuben van Selm.

Puzzle #5 is from listener Andy Brice.

Puzzle #6 is from listener Anne Joroch, who sent this link.

Puzzle #7 is from listener Steve Carter and his wife, Ami, inspired by an item in Jim Steinmeyer’s 2006 book The Glorious Deception.

Puzzle #8 is from Agnes Rogers’ 1953 book How Come? A Book of Riddles, sent to us by listener Jon Jerome.

You can listen using the player above, download this episode directly, or subscribe on Google Podcasts, on Apple Podcasts, or via the RSS feed at https://futilitycloset.libsyn.com/rss.

Many thanks to Doug Ross for providing the music for this whole ridiculous enterprise, and for being my brother.

If you have any questions or comments you can reach us at podcast@futilitycloset.com. Thanks for listening!

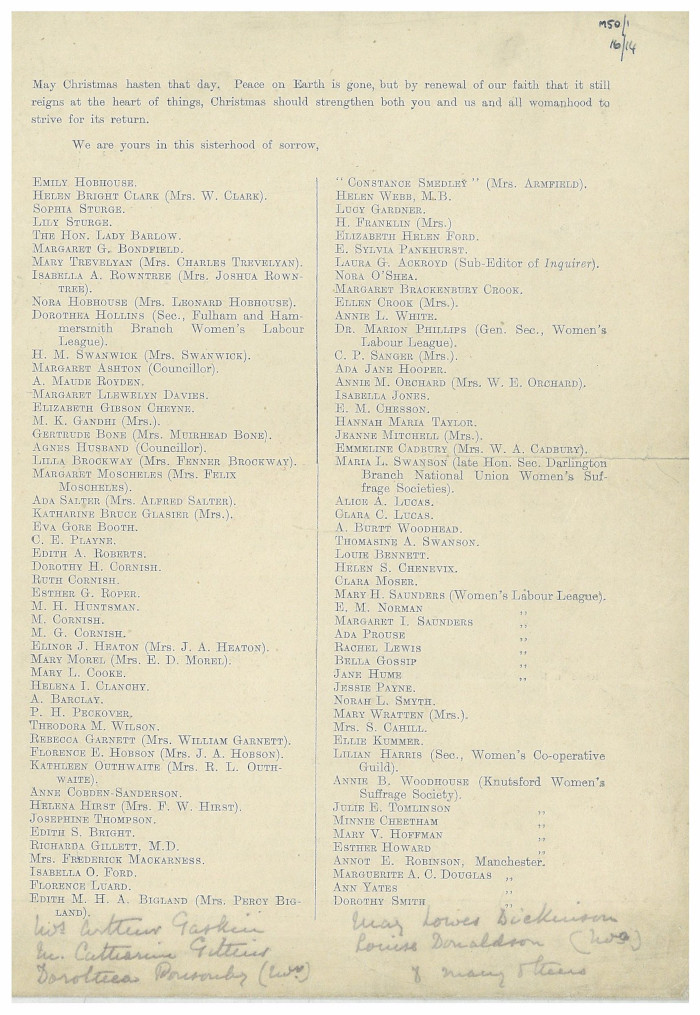

In December 1914, as the first Christmas of World War I approached, 101 British women suffragists sent a holiday message “To the Women of Germany and Austria.”

“Some of us wish to send you a word at this sad Christmastide,” it ran. “The Christmas message sounds like mockery to a world at war, but those of us who wished, and still wish, for peace may surely offer a solemn greeting to such of you who feel as we do.”

Though our sons are sent to slay each other, and our hearts are torn by the cruelty of this fate, yet through pain supreme we will be true to our common womanhood. We will let not bitterness enter into this tragedy, made sacred by the life-blood of our best, nor mar with hate the heroism of their sacrifice. Though much has been done on all sides you will, as deeply as ourselves, deplore — shall we not steadily refuse to give credence to those false tales so free told us, each of the other?

We hope it may lessen your anxiety to learn we are doing our utmost to soften the lot of your civilians and war prisoners within our shores, even as we rely on your goodness of heart to do the same for ours in Germany and Austria.

The following spring they received a reply:

If English women alleviated misery and distress at this time, relieved anxiety, and gave help irrespective of nationality, let them accept the warmest thanks of German women and the true assurance that they are and were prepared to do likewise. In war time we are united by the same unspeakable suffering of all nations taking part in the war. Women of all nations have the same love of justice, civilization and beauty, which are all destroyed by war. Women of all nations have the same hatred for barbarity, cruelty and destruction, which accompany every war.

Women, creators and guardians of life, must loathe war, which destroys life. Through the smoke of battle and thunder of cannon of hostile peoples, through death, terror, destruction, and unending pain and anxiety, there glows like the dawn of a coming better day the deep community of feeling of many women of all nations.

It was signed by 155 women of Germany and Austria.