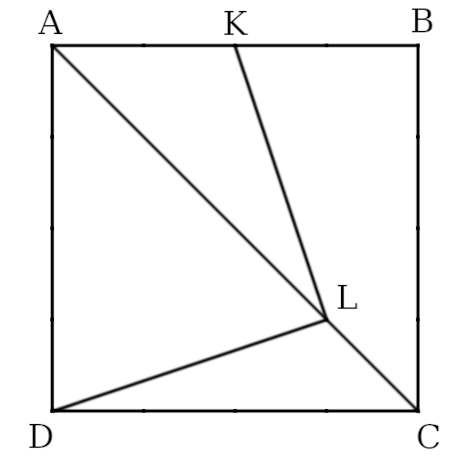

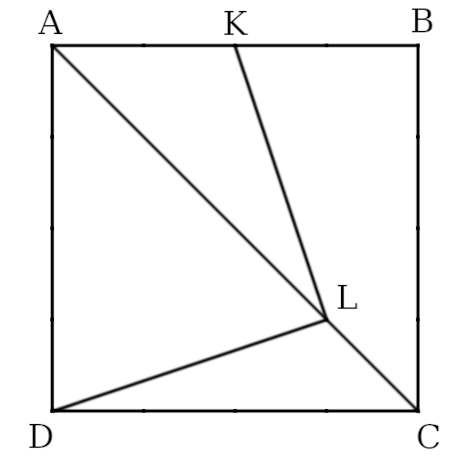

A brainteaser by Y. Bogaturov, via Quantum, November-December 1991:

In square ABCD, point L divides diagonal AC in the ratio 3:1 and K is the midpoint of side AB. Prove that angle KLD is a right angle.

A brainteaser by Y. Bogaturov, via Quantum, November-December 1991:

In square ABCD, point L divides diagonal AC in the ratio 3:1 and K is the midpoint of side AB. Prove that angle KLD is a right angle.

CUNY philosopher Noël Carroll notes, “It is a remarkable fact about the creatures of horror that very often they do not seem to be of sufficient strength to make a grown man cower. A tottering zombie or a severed hand would appear incapable of mustering enough force to overpower a co-ordinated six-year-old. Nevertheless, they are presented as unstoppable, and this seems psychologically acceptable to audiences.” Why is this?

(From his Philosophy of Horror, 1990.)

As children Maurice Baring and his brother Hugo invented a gibberish language in which the word for yes was Sheepartee and the word for no was Quiliquinino. This grew so tiresome to the adults around them that they were eventually threatened with a whipping:

The language stopped, but a game grew out of it, which was most complicated, and lasted for years even after we went to school. The game was called ‘Spankaboo.’ It consisted of telling and acting the story of an imaginary continent in which we knew the countries, the towns, the government, and the leading people. These countries were generally at war with one another. Lady Spankaboo was a prominent lady at the Court of Doodahn. She was a charming character, not beautiful nor clever, and sometimes a little bit foolish, but most good-natured and easily taken in. Her husband, Lord Spankaboo, was a country gentleman, and they had no children. She wore red velvet in the evening, and she was bien vue at Court.

There were hundreds of characters in the game. They increased as the story grew. It could be played out of doors, where all the larger trees in the garden were forts belonging to the various countries, or indoors, but it was chiefly played in the garden, or after we went to bed. Then Hugo would say: ‘Let’s play Spankaboo,’ and I would go straight on with the latest events, interrupting the narrative every now and then by saying: ‘Now, you be Lady Spankaboo,’ or whoever the character on the stage might be for the moment, ‘and I’ll be So-and-so.’

“Everything that happened to us and everything we read was brought into the game — history, geography, the ancient Romans, the Greeks, the French; but it was a realistic game, and there were no fairies in it and nothing in the least frightening. As it was a night game, this was just as well.”

(From his Puppet Show of Memory, 1922.)

Gertrude Stein’s 1935 lecture “Poetry and Grammar” includes a section on punctuation, for which she had a peculiar disdain:

There are some punctuations that are interesting and there are some punctuations that are not. Let us begin with the punctuations that are not. Of these the one but the first and the most the completely most uninteresting is the question mark. The question mark is alright when it is all alone when it is used as a brand on cattle or when it could be used in decoration but connected with writing it is completely entirely completely uninteresting.

In 2000, Kenneth Goldsmith rather archly removed the words from this passage and offered the bare punctuation as a poem titled “Gertrude Stein’s Punctuation from ‘Gertrude Stein on Punctuation'” (the full passage and the poem are both here). Goldsmith did the same thing with the punctuation chapter from Strunk & White’s Elements of Style and with Molly Bloom’s soliloquy at the end of Ulysses — a few hyphens and a period.

Carl Reuterswärd’s 1960 novel Prix Nobel consists entirely of punctuation marks. Reuterswärd felt that ordinary writing robs punctuation of its meaning; the surrounding words convey concepts and the commas, colons, and periods simply help to mark it. Removing the words, though, revealed an “interesting alternative: not to ignore syntax but certainly to forgo ‘the preserved meaning of others.’ The ‘absence’ that occurs is not mute. For want of ‘governing concepts’ punctuation marks lose their neutral value. They begin to speak an unuttered language out of that already expressed. This cannot help producing a ‘colon concept’ in you, a need of exclamation, of pauses, of periods, of parentheses.”

In 2005, Chinese novelist Hu Wenliang offered 140,000 yuan ($16,900 U.S.) to the reader who could decipher his novel «?», which consists entirely of punctuation marks.

The autobiography of the American eccentric “Lord” Timothy Dexter (1748-1806) contains 8,847 words and no punctuation. When readers complained, he added a page of punctuation marks to the second edition, inviting them to “peper and solt it as they plese.”

06/30/2022 More: Reader Kevin Orlin Johnson sent this poem by David Morice, from the February 2012 issue of Word Ways:

% , & –

+ . ? /

“ :

% ;

+ $ [ \

It’s a limerick:

Percent comma ampersand dash

Plus period question mark slash

Quotation mark colon

Percent semicolon

Plus dollar sign bracket backslash

(Thanks, Kevin.)

A problem from the February 2006 issue of Crux Mathematicorum:

In a set of five positive integers, show that it’s always possible to choose three such that their sum is a multiple of 3.

The bird known as the red phalarope in North America is the grey phalarope in England — it bears red plumage during its breeding season, but the British see only its drab winter dress.

A poem by Lord Kennet, from my notes:

I live in hope some day to see

The crimson-necked phalarope;

(Or do I, rather, live in hope

To see the red-necked phalarope?)

Welsh mathematician Robert Recorde’s 1543 textbook Arithmetic: or, The Ground of Arts contains a nifty algorithm for multiplying two digits, a and b, each of which is in the range 5 to 9. First find (10 – a) × (10 – b), and then add to it 10 times the last digit of a + b. For example, 6 × 8 is (4 × 2) + (10 × 4) = 48.

This works because (10 – a)(10 – b) + 10(a + b) = 100 + ab, and it saves the student from having to learn the scary outer reaches of the multiplication table — they only have to know how to multiply digits up to 5.

(From Stanford’s Vaughan Pratt, in Ed Barbeau’s column “Fallacies, Flaws, and Flimflam,” College Mathematics Journal 38:1 [January 2007], 43-46.)

Edith Wharton was “reading” before she knew the alphabet. As a young girl she found Washington Irving’s 1832 book Tales of the Alhambra in her parents’ library and discovered “richness and mystery in the thick black type”:

At any moment the impulse might seize me; and then, if the book was in reach, I had only to walk the floor, turning the pages as I walked, to be swept off full sail on the sea of dreams. The fact that I could not read added to the completeness of the illusion, for from those mysterious blank pages I could evoke whatever my fancy chose. Parents and nurses, peeping at me through the cracks of doors (I always had to be alone to ‘make up’), noticed that I often held the book upside down, but that I never failed to turn the pages, and that I turned them at about the right pace for a person reading aloud as passionately and precipitately as was my habit.

Only later did she learn to value books for their substance rather than as vessels for her own imagination. “[M]y father, by dint of patience, managed to drum the alphabet into me; and one day I was found sitting under a table, absorbed in a volume which I did not appear to be using for improvisation. My immobility attracted attention, and when asked what I was doing, I replied: ‘Reading.'”

(From her 1934 autobiography A Backward Glance.)

Convalescing from pneumonia one winter, Mary L. Daniels occupied herself by collecting all the digressions to the reader in the 47 novels of Anthony Trollope. Victorian fiction permitted a writer to stop in mid-story and expound his own views, and Trollope indulged this privilege with staggering frequency — together his digressions fill nearly 400 pages of close-set type, practically a novel’s worth in themselves. Some examples:

“These digressions are pure Trollope — at least of that moment — undiluted by plot, character, theme, or modern exegesis,” Daniels writes. “By studying these digressions alone, we should be able to trace any changes in Trollope’s thinking without reference to what we think he meant or to what a particular character said or did.” The whole list is here.