“My own opinion is that belief is the death of intelligence. As soon as one believes a doctrine of any sort, or assumes certitude, one stops thinking about that aspect of existence. The more certitude one assumes, the less there is left to think about, and a person sure of everything would never have any need to think about anything and might be considered clinically dead under current medical standards, where the absence of brain activity is taken to mean that life has ended.” — Robert Anton Wilson

Outreach

The Statue of Liberty’s disembodied arm stood in Madison Square from 1876 to 1882. It had been agreed that Frédéric Bartholdi would create the statue while the United States paid for the pedestal. Americans were a bit behindhand in offering donations, so Bartholdi sent along the arm and torch to help inspire contributions.

It took six years of benefit concerts, auctions, souvenir photos, and other mementos, but the full statue was finally dedicated on Liberty Island on October 28, 1886.

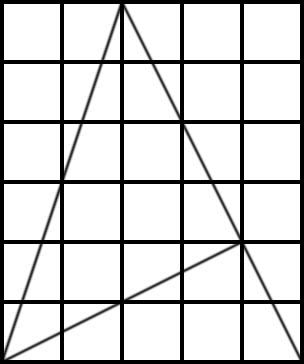

Proof Without Words

In the January 2001 issue of the College Mathematics Journal, University of Calgary mathematician Jonathan Schaer offers this simple proof that arctan 1 + arctan 2 + arctan 3 = π. The sum of the angles of this large triangle is 180°. And the diagram shows that its lower left angle is arctan 3, its lower right angle is arctan 2, and its top angle is part of an isosceles right triangle. So arctan 1 + arctan 2 + arctan 3 = 180°, or π radians. “No words, even no symbols!”

(“Miscellanea,” College Mathematics Journal 32:1, 68-71.)

Rotating Office

Actress Ilka Chase married Louis Calhern in 1926, but he divorced her the following year to marry Julia Hoyt.

Sorting through her possessions afterward, she discovered a set of engraved calling cards that she’d had printed with the name Mrs. Louis Calhern.

“They were the best cards — thin, flexible parchment, highly embossed — and it seemed a pity to waste them, and so I mailed the box to my successor,” she wrote later.

“But aware of Lou’s mercurial marital habits, I wrote on the top one, ‘Dear Julia, I hope these reach you in time.’

“I received no acknowledgment.”

(From Chase’s 1945 autobiography Past Imperfect.)

In a Word

volant

adj. engaged in flight

espieglerie

n. impish or playful behaviour; mischief

apopemptic

adj. pertaining to leave-taking or departing

réclame

n. publicity or notoriety

In 1953, 61-year-old British ace Christopher Draper flew an Auster monoplane under 15 of the 18 bridges on the Thames, negotiating 50-foot arches at 90 mph.

“I did it for the publicity,” he told the press. “For 14 months I have been out of a job, and I’m broke. I wanted to prove that I am still fit, useful and worth employing. … It was my last-ever flight — I meant it as a spectacular swan song.” He was fined 10 guineas.

Night Life

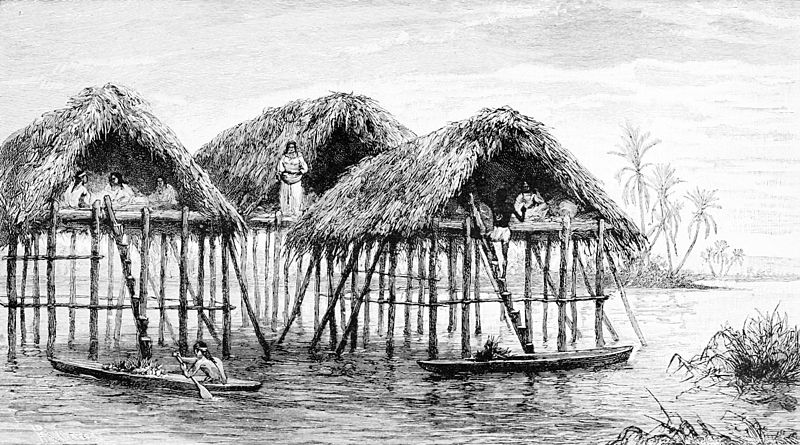

Suppose that your dream-life underwent a remarkable change. Suppose that on going to bed at home and falling asleep, you found yourself to all appearances waking up in a hut raised on poles at the edge of a lake. A dusky woman, whom you realize to be your wife, tells you to go out and catch some fish. The dream continues with the apparent length of an ordinary human day, replete with an appropriate and causally coherent variety of tropical incident. At last you climb up the rope ladder to your hut and fall asleep. At once you find yourself awaking at home, to the world of normal responsibilities and expectations. The next night life by the side of the tropical lake continues in a coherent and natural way from the point at which it left off. Your wife says, ‘You were very restless last night. What were you dreaming about?’ and you find yourself giving her a condensed version of your English day. And so it goes on. Injuries given in England leave scars in England, insults given at the lakeside complicate lakeside personal relations. One day in England, after a heavy lunch, you fall asleep in your armchair and dream of yourself, or find yourself, waking up in the middle of the night beside the lake. Things get too much for you at the lakeside, your wife has departed with all the cooking-pots, and you suspect that she is urging the villagers to sacrifice you to the moon. So you fall on your fish-spear and from that moment on your English slumbers are disturbed no more than in the old pre-lakeside days.

— Anthony Quinton, Thoughts and Thinkers, 1982

“Is such a two-space reality conceivable?” asks Peg Tittle in What If…: Collected Thought Experiments in Philosophy (2016). “That is, is it conceivable that we could live in two different but real spaces?”

See Figure and Ground.

Last Words

On Sept. 8, 1880, an explosion tore through the Seaham Colliery, a coal mine in County Durham in the North of England, filling both shafts with debris and trapping scores of men in the burning seams. Most of the 164 dead were found where they had been working, suggesting that death had come quickly, but some of those farther from the shafts appear to have survived for hours or even longer in pockets of air — the oil in some of their lamps was exhausted. Some of these men had had time to leave messages to those who might find them:

September 8 1880

E.Hall and J.Lonsdale died at half-past 3 in the morning.W.Murray and W.Morris and James Clarke visited the rest on half-past nine in the morn and all living in the incline,

Yours truly,

W.Murray, Master-Shifter

Five o’ clock, we have been praying to God

The Lord has been with us, we are all ready for heaven – Ric Cole, half past 2 o’ clock Thursday

Bless the Lord we have had a jolly prayer meeting, every man ready for glory. Praise the Lord. Sign.R.Cole

Dear Margaret,

There was 40 of us altogether at 7am. Some was singing hymns but my thoughts was on my little Michael that him and I would meet in heaven at the same time. Oh Dear wife, God save you and the children, and pray for me … Dear wife, Farewell. My last thoughts are about you and the children. Be sure and learn the children to pray for me. Oh what an awful position we are in ! Michael Smith, 54 Henry Street

The last had been scratched on a tin water bottle with a rusty nail by Michael Smith, who had left his dying infant son to go to work in the mine that morning. The son died on the same day.

(From Durham Records Online.)

Toeholds

Set into the corner of Seventh Avenue and Christopher Street in Manhattan’s West Village is a triangular plaque reading PROPERTY OF THE HESS ESTATE WHICH HAS NEVER BEEN DEDICATED FOR PUBLIC PURPOSES. The “Hess triangle” is a remnant from a property dispute that unfolded here 100 years ago: The city was claiming eminent domain in order to demolish hundreds of buildings and expand the subway, but surveyors overlooked this 65-centimeter triangle, owned by Philadelphia landlord David Hess. Hess, outraged at the loss of his five-story apartment building, refused to donate the triangle to the public and added the plaque as a sort of existential revenge. In 1938 it was sold to the adjacent cigar store, and today it’s owned by a local realty corporation, the smallest plot of land in New York City.

Related: In 1973, artist Gordon Matta-Clark bought 13 unused pieces of land that were left over when property lines were redrawn in the borough of Queens. He paid between $25 and $75 for each. The sites are often irregular or isolated, located where other properties meet in a block, some measuring as little as 2×3 feet.

“When I bought those properties at the New York City Auction, the description of them that always excited me the most was ‘inaccessible’,” he said. “They were a group of fifteen micro-panels of land in Queens, leftover properties from an architect’s drawing. One or two of the prize ones were a foot strip down somebody’s driveway and a square foot of sidewalk. And the others were kerbstone and gutterspace. What I basically wanted to do was to designate spaces that wouldn’t be seen and certainly not occupied. Buying them was my own take on the strangeness of existing property demarcation lines. Property is so all-pervasive. Everyone’s notion of ownership is determined by the use factor.”

(Jeffrey Kastner and Brian Wallis, Land & Environmental Art, 2005.)

Who’s Who

John Bevis’ 2010 book Aaaaw to Zzzzzd: The Words of Birds collects the nonsense words that birders have invented to try to convey bird calls and songs:

ag ag ag ag arr: fulmar

beesh: scaled quail

bek bek bek: red-throated loon

chack-weet weet-chack: northern wheater

djadjadja: twite

ee woomp: bittern

hup-hup-a-hwooo: red-billed pigeon

kakakowlp-kowlp: yellow-billed cuckoo

kuk-kuk-cow-cow-cow-cowp-cowp: pied-billed grebe

quickquickquickquick: cuckoo

seedle seedle seedle chup chup: hermit warbler

tiutiu-tiutiutiuk-swee: yellowhammer

trrrrk: wrentit

tzew-zuppity-zuppity-zup: rufous hummingbird

weeta weeta weeta che che che: Lucy’s warbler

wheet-tsack-tsack-tsack: stonechat

zeeda-zeeda-zeeda-sissi-peeso: goldcrest

zoo zee zoo zoo zee: black-throated green warbler

Other interpreters have used actual words — the white-eyed vireo says, “Pick up the beer check quick!”

The Watlington White Mark

In 1764 Oxfordshire squire Edward Horne decided that the parish church of St Leonard on Watlington Hill would look more impressive with a spire. So he gave it one: By cutting a narrow mark 270 feet long into the chalk soil beyond the building, he was able to perch a foreshortened triangle atop the church when it was viewed in perspective from his house. Local residents maintain the mark to this day.