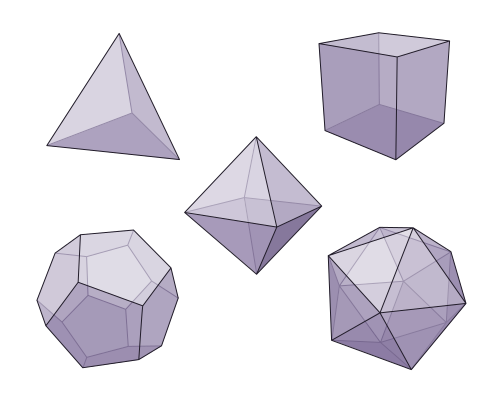

Conducting a workshop on paper folding and geometry for a group of gifted 10-year-olds in 1977, Santa Clara University mathematician Jean Pedersen passed around a collection of polyhedra and asked the students which shapes they’d classify as “regular.” To her surprise, the only one who chose the five platonic solids was Peter Wilson, a blind student.

The others immediately responded, “That’s not fair, Peter’s blind!” So Pedersen agreed to let them try again, this time feeling the models with their eyes closed. Now every student chose the five platonic solids.

“I’m not sure what all the ramifications of these events are,” Pedersen wrote in a letter to the Mathematical Intelligencer, “but begin with this: we can perceive things with just our hands that we miss when we use both our eyes and our hands. Sometimes less really is more.”

(Jean Pedersen, “Seeing the Idea,” Mathematical Intelligencer 20:4 [Fall 1998], 6.)