“However often you may have done them a favor, if you once refuse they forget everything except your refusal.” — Pliny the Younger

Hall’s Marriage Theorem

Suppose we have a group of n men and n women. Each of the women can find some subset of the men whom she would be happy to marry. And each of the men would be happy with any woman who will have him. Is it always possible to pair everyone off into happy marriages?

Clearly this won’t work if, for example, two of the women have their hearts set on the same man and won’t be happy with anyone else. In general, for any subset of the women, we need to be sure that they can reconcile their preferences so that each of them finds a mate.

Surprisingly, though, that’s all that’s required. So long as every subset of women can collectively express interest in a group of men at least as numerous as their own, it will always be possible to marry off the whole group into happy couples.

The theorem was proved by English mathematician Philip Hall in 1935. Another application of the same principle: Shuffle an ordinary deck of 52 playing cards and deal it into 13 piles of 4 cards each. Now it’s always possible to assemble a run of 13 cards, ace through king, by drawing one card from each pile.

Key Testimony

Here’s a piano reciting the Proclamation of the European Environmental Criminal Court.

It was programmed by Austrian composer Peter Ablinger for World Venice Forum 2009, sponsored by Italy’s Academy of Environmental Sciences. Ablinger wanted to convey an environmental message by musical means, so he asked Berlin elementary school student Miro Markus to read the text and then translated the frequency spectrum of Markus’ voice to the piano.

“I break down this phonography — meaning a recording of something, the voice, in this case — in individual pixels, one can say,” Ablinger explained. “And if I have the possibility of a rendering in a fairly high resolution (and that I only get with a mechanical piano), then I in fact restore some kind of continuity.”

“Therefore, with a little practice, or help or subtitling, we actually can hear a human voice in a piano sound.”

The Silent Trade

The 15th-century Venetian navigator Alvise Cadamosto describes a curious convention by which the Mauritanian Azanaghi traded salt with the merchants of Mali:

All those who have the salt pile it in rows, each marking his own. Having made these piles, the whole caravan retires half a day’s journey. Then there comes another race of blacks who do not wish to be seen or to speak. They arrive in large boats, from which it appears that they come from islands, and disembark. Seeing the salt, they place a large quantity of gold opposite each pile, and then turn back, leaving salt and gold. When they have gone, the Negroes who own the salt return: if they are satisfied with the quantity of gold, they leave the salt and retire with the gold. Then the blacks of the gold return, and remove those piles which are without gold. By the other piles of salt they place more gold, if it pleases them, or else they leave the salt. In this way, by long and ancient custom, they carry on their trade without seeing or speaking to each other.

In this way different cultures can trade safely without speaking the same language. It’s called the “silent trade”; Herodotus describes a similar practice between Carthage and West Africa, and it’s been reported also in Siberia, Lapland, Timor, Sumatra, India, Sri Lanka, and New Guinea.

Why didn’t the Malians simply take the salt? Presumably because trade was more valuable to them in the long run. I wonder how such a custom gets started in the first place, though.

Landscape Portrait

In Johannes Kepler’s 1608 novel Somnium, a demon describes how the shapes of the terrestrial continents appear to an observer on the moon:

On the eastern side [toward the Atlantic Ocean] it looks like the front of the human head cut off at the shoulders [Africa] and leaning forward to kiss a young girl [Europe] in a long dress [Thrace and the Black Sea regions], who stretches her hand back [Britain] to attract a leaping cat [Scandinavia]. The bigger and broader part of the spot [Asia], however, extends westward without any apparent configuration. In the other half of Volva [Earth] the brightness is more widely diffused [the two oceans] than the spot [the American continent]. You might call it the outline of a bell [South America] hanging from a rope [Nicaragua, Yucatán, Popayán] and swinging westward. What lies above [Brazil] and below [North America] cannot be likened to anything.

The two “halves” are the Old World and the New. East and west, upper and lower are reversed in the lunar perspective. Kepler mistakenly believed that continents would appear as dark “spots” against lighter oceans; he later credited Galileo with correcting this error.

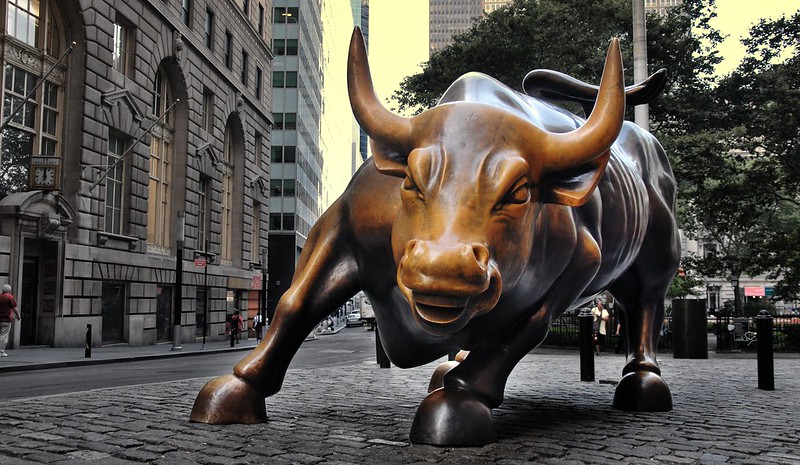

Free Enterprise

Charging Bull, the bronze sculpture that’s become a ubiquitous symbol of Wall Street, was not commissioned by New York City or anyone in the financial district. Artist Arturo Di Modica spent $360,000 to create the three-ton statue, trucked it to Lower Manhattan, and on Dec. 15, 1989, left it in front of the New York Stock Exchange as a Christmas gift to the people of New York. Police impounded it, but after a public outcry the city decided to install it two blocks south of the exchange.

Since New York doesn’t own it, technically it has only a temporary permit to remain on city property. But after 32 years, it appears to have become a permanent fixture.

Black and White

Shop Talk

A dictionary of thieves’ slang, from Life in Sing Sing, by “Number 1500,” 1904:

Are you next?: Do you understand? Be wise

Crushing the jungle: Escaping from prison

Cracking the jug: Forcing an entrance into a bank

Busting the tag on a rattler: Breaking the seal on a freight car

Busting the bulls at the big show: Fighting with the police at the circus

Banging supers at the red wagon: Stealing watches at the ticket wagon

Hoisting a slab of stones: Stealing a tray of diamonds

He got whipped back to the Irish club house: He was remanded to the police station

Hitting the pipe at a hop-joint: Smoking opium in an opium joint

He busted the collar’s smeller: He broke the officer’s nose

The stall got his slats kicked in: The thief had his ribs broken

The gun slammed a rod to his nut: The thief put a pistol to his head

He pigged with the darb: He absconded with the money

The yeg men blew the gopher: The safe crackers forced open the doors of the safe with explosives

I went to the coast with a mob of paper-layers, but graft was on the fritzer. I blew out and rung in with a couple of penny-weighters. A Tommy and his papa. Everything was rosy, the cush was coming strong and I was patting this ginny on the hump, but I was a sooner. The Tommy got a swelled head and we split for all. I did the grand to Chicago and filled in with a yeg mob. We got a country jug on our first touch, but the box wasn’t heavy enough for five. They had a plant further on. But we had to wait till one of the mob went for some soup; as I had plenty of the darb I blew away and beat it back to Chic, and framed in with a couple of guns who were working east on the rattlers. We got the stuff all right. Well, I’m off to the joint to smoke up, so-so.

“I went to California with others to pass worthless checks. There wasn’t any money in it, so I left them and went with two expert thieves who make it a practice to rob jewelers, a woman and her lover. Everything looked bright. I was obtaining money easily and I was congratulating myself on my good fortune, but I was too hasty. This woman got independent and we parted for good. I purchased a first-class ticket to Chicago and met a gang of safe burglars whom I joined. Our first theft was the burglary of a safe in a suburban bank. The amount of money obtained was insufficient to repay five men for their trouble. They had in view another place to rob, but we had to wait while one of the men went for some nitroglycerine. As I had plenty of money, I parted from them and returned to Chicago. There I met two pickpockets who were going east on the cars with the intention of plying their trade. We stole a lot of money. And now I’m off to the opium den to smoke some opium. Good-by.”

The President’s Mystery

Franklin Roosevelt was a voracious reader of crime novels. “Hundreds are published every year, but even in the good ones, there is a sameness,” he complained over lunch to Liberty Magazine editor Fulton Oursler one day in 1935. “Someone finds the corpse, and then the detective tracks down the murderer.”

Oursler asked him whether he had any better ideas. He did: “How can a man disappear with five million dollars of his own money in negotiable form and not be traced?” Roosevelt said he had carried that question in his mind for years but had not solved it himself.

The editor knew a marketable idea when he heard one, and he recruited six of the period’s top mystery writers to work on a chain novel that appeared serially in the magazine beginning that November. (The writers were Rupert Hughes, Samuel Hopkins Adams, Anthony Abbott, Rita Weiman, S.S. Van Dine, and John Erskine.)

A year later the story was made into a film, above, with the memorable credit “Story Conceived by Franklin D. Roosevelt.” FDR remains the only president to earn a film-writing credit while in office.

Freeze!

Here’s a lost art: The tableau vivant, or “living picture,” was a form of popular entertainment in which the actors took up poses but did not speak or move. (This one presents the original cast of Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Sleeping Beauty.)

In our era of ubiquitous video it’s hard to remember how important this was — it formed a sort of living bridge between painting and the stage, representing dramatic moments in three dimensions that could be studied and admired as part of the real world. Sometimes stories were told through a series of connected tableaux, a technique that would lead eventually to modern storyboards and comic strips.

The form also inspired a curious practice: Censorship laws in Britain and the United States forbade actresses to move onstage when they were unclothed, so exhibitors began to present nude women in tableaux vivants, imitating works of classical art. The presenters could claim that this was edifying, the audiences got their erotic entertainment, and the production was allowed to go on — so long as the women didn’t move.