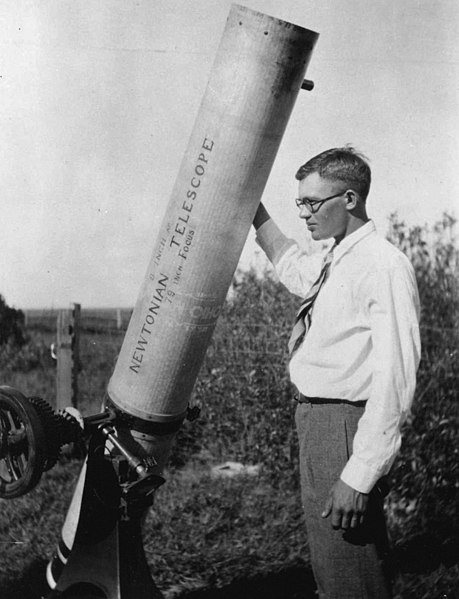

Astronomer Clyde Tombaugh assembled his first telescope from spare parts on his family’s Kansas farm — the crankshaft of a 1910 Buick, a cream-separator base, and mechanical components from a straw spreader. He used this to make sketches of Jupiter and Mars that so impressed the astronomers at Lowell Observatory that they gave him a job there.

Years later, after he had made his name by discovering Pluto, the Smithsonian Institution asked if it could exhibit this early instrument. He told them he was still using it — he was making observations from his backyard near Las Cruces, N.M., until shortly before his death in 1997.

“Its mirror was hand-ground and tested in a storm cellar,” wrote Peter Manly in Unusual Telescopes in 1991. “It’s not the most elegant-looking optical instrument I’ve ever used, but it is one of the better planetary telescopes around. … Because of its role in the history of astronomy, I would classify this as one of the more important telescopes in the world.”