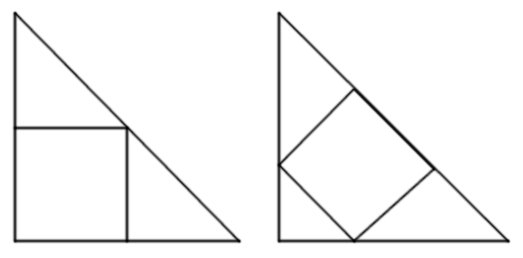

A square has been inscribed in each of two congruent isosceles right triangles. Which square is larger?

A square has been inscribed in each of two congruent isosceles right triangles. Which square is larger?

Korean sculptor Yi Hwan-Kwon presents his subjects as they might appear in a distorted mirror, but he renders them as three-dimensional sculptures, giving a disorienting effect of skewed perspective even when they’re viewed normally.

(Thanks, Allen.)

Designed in 1804, the Grand Shaft, at the Western Heights of Dover, is a triple helix, the only such staircase in Britain. As with Vatican City’s Bramante Staircase, this design accommodates a large number of passengers while minimizing interference among them — using it, a large number of troops might quickly descend the 140 feet from the heights to the town below, while others might even ascend at the same time, using a different spiral.

In 1812 a Mr. Leith of Walmer rode his horse up the stair for a bet, and local legend has it that during Victorian times the separate spirals were assigned to “officers and their ladies,” “sergeants and their wives,” and “soldiers and their women.”

(Thanks, Dave.)

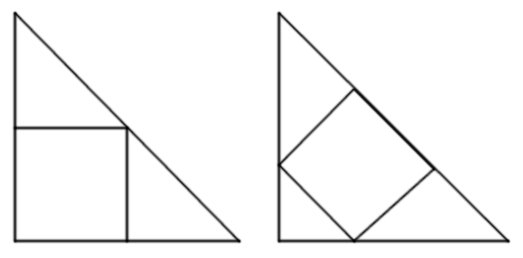

Biologist Jonathan Eisen, who coined the term phylogenomics, called this “perhaps the best genomics Venn diagram ever.” The six-set diagram, published by Angélique D’Hont and her colleagues in Nature in 2012, presents the number of gene families that the banana shares with five other species.

“What the diagram says is that over time the 7,674 gene clusters shared by the six species did not change much in these lineages, as opposed to the 759 clusters specific to the banana (Musa acuminata), for example,” explains Anne Vézina at ProMusa. “Although the genes in these clusters probably share common ancestors with other species, they have since changed to the point that they haven taken on new functions.”

Here’s a similar (5-set) diagram relating to conifers.

(Angélique D’Hont et al., “The Banana (Musa acuminata) Genome and the Evolution of Monocotyledonous Plants,” Nature 488:7410 [2012], 213-217.) (Thanks, David.)

A little oddity: In Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, a sentence of 16 words (“The change will do you good, and you must be sure to go and see Ellen,” spoken to Newland Archer by his wife May) has a meaning of 221 words:

It was the only word that passed between them on the subject; but in the code in which they had both been trained it meant: ‘Of course you understand that I know all that people have been saying about Ellen, and heartily sympathise with my family in their effort to get her to return to her husband. I also know that, for some reason you have not chosen to tell me, you have advised her against this course, which all the older men of the family, as well as our grandmother, agree in approving; and that it is owing to your encouragement that Ellen defies us all, and exposes herself to the kind of criticism of which Mr. Sillerton Jackson probably gave you, this evening, the hint that has made you so irritable…. Hints have indeed not been wanting; but since you appear unwilling to take them from others, I offer you this one myself, in the only form in which well-bred people of our kind can communicate unpleasant things to each other: by letting you understand that I know you mean to see Ellen when you are in Washington, and are perhaps going there expressly for that purpose; and that, since you are sure to see her, I wish you to do so with my full and explicit approval — and to take the opportunity of letting her know what the course of conduct you have encouraged her in is likely to lead to.’

Azerbaijani artist Faig Ahmed applies surreal distortions to traditional Islamic rugs: They seem to melt, warp, and pixelate, though they’re all created using traditional weaving techniques.

“I love being a hostage [to tradition], because it’s a quiz and you have to take it to set yourself free,” he told Art Radar. “I think we are never completely free anyway, but you should exactly know where your own cage ends.”

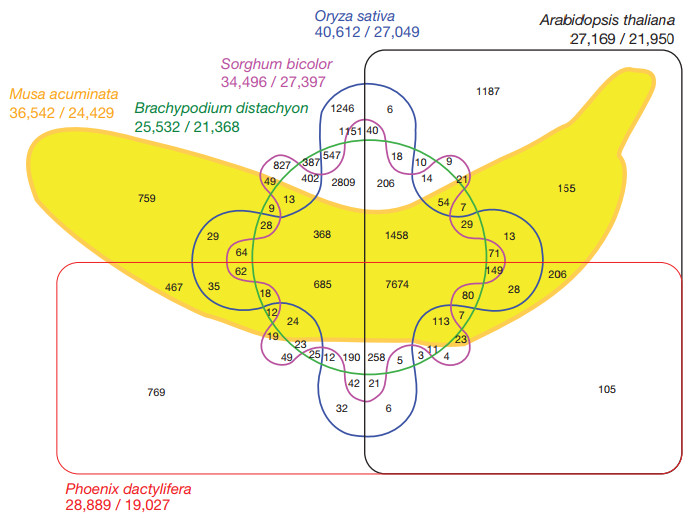

In 1912, 4-year-old Bobby Dunbar went missing during a family fishing trip in Louisiana. Eight months later, a boy matching his description appeared in Mississippi. But was it Bobby Dunbar? In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll describe the dispute over the boy’s identity.

We’ll also contemplate a scholarship for idlers and puzzle over an ignorant army.

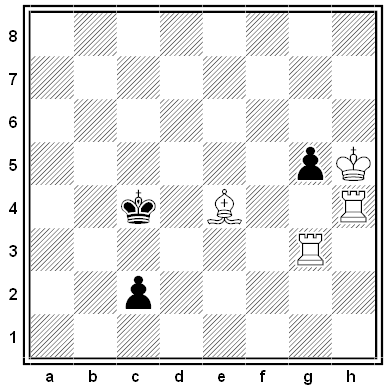

This problem, by V. Tchepizhni, won fifth prize in the Bohemian Centenary Tourney of 1962. It’s four puzzles in one:

(a) The diagrammed position.

(b) Turn the board 90 degrees clockwise.

(c) Turn the board 180 degrees.

(d) Turn the board 270 degrees clockwise.

Each of the resulting positions presents a helpmate in two: Black moves first, then White, then Black, then White, the two sides cooperating to reach a position in which Black is checkmated. What are the solutions?

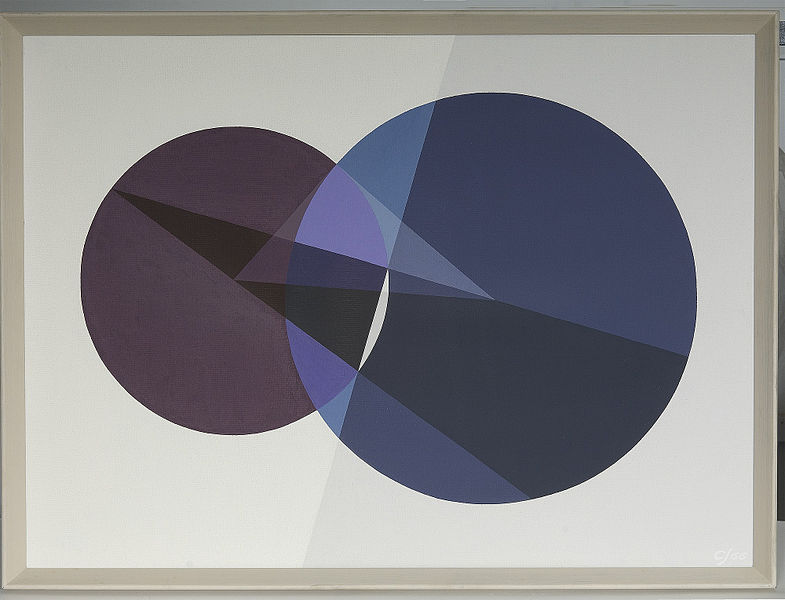

Crockett Johnson, author of the 1955 children’s book Harold and the Purple Crayon, was trained as an engineer and produced more than 100 paintings based on diagrams used in the proofs of classical theorems. This one, Polar Line of a Point and a Circle (Apollonius), appears to have been inspired by a figure in Nathan A. Court’s 1966 College Geometry. The two circles are orthogonal: They cut one another at right angles. And as the square of the line connecting their centers equals the sum of the squares of their radii, these three segments form a right triangle.

Johnson was inspired to this work by his admiration of classical Greek architecture. Sitting in a restaurant in Syracuse in 1973, he managed to construct a heptagon using seven toothpicks and the edges of a menu and a wine list, a construction that had eluded the Greeks. (He found later that Archibald Finlay had illustrated similar constructions in 1959.)

(Stephanie Cawthorne and Judy Green, “Harold and the Purple Heptagon,” Math Horizons 17:1 [2009], 5-9.)