A problem from the Leningrad Mathematical Olympiad: A and B take turns removing matches from a pile. The pile starts with 500 matches, A goes first, and the player who takes the last match wins. The catch is that the quantity that each player withdraws on a given turn must be a power of 2. Does either player have a winning strategy?

Riddles

From John Winter Jones’ Riddles, Charades, and Conundrums, 1822:

What is that which a coach always goes with, cannot go without, and yet is of no use to the coach?

Noise.

***

From Routledge’s Every Boy’s Annual, 1864:

Why is O the noisiest of the vowels?

Because all the rest are inaudible (in audible).

***

From Mark Bryant’s Riddles: Ancient & Modern, 1983:

What is big at the bottom, little at the top, and has ears?

A mountain (it has mountaineers!).

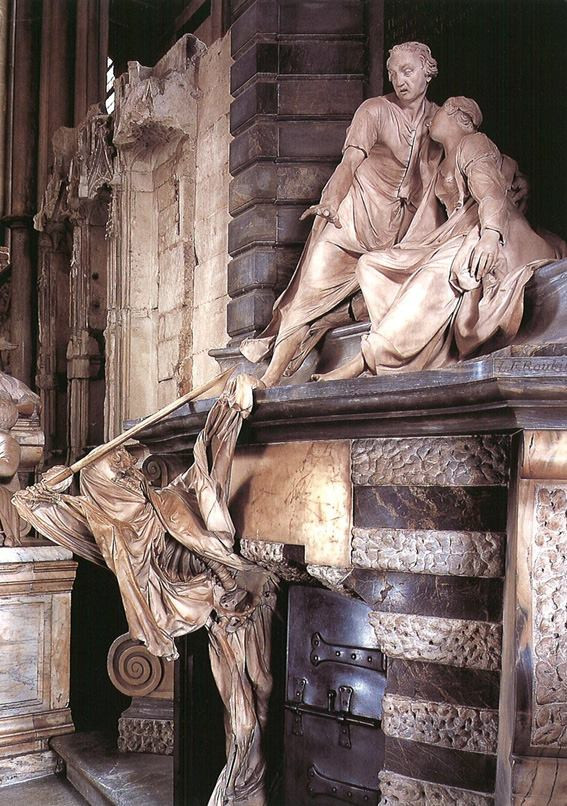

The Nightingale Monument

Elizabeth Nightingale died of shock at a violent stroke of lightning following the premature birth of her daughter in 1731. In his will, her son ordered the erection of this monument, which was created by Louis Francois Roubiliac and stands in Westminster Abbey. Elizabeth is supported by her husband, who tries in horror to ward off the stroke of death. Washington Irving called it “among the most renowned achievements of modern art.”

The Abbey’s website says, “The idea for this image may have come from a dream that Elizabeth’s brother in law (the Earl of Huntingdon) had experienced when a skeleton had appeared at the foot of his bed, which then crept up under the bedclothes between husband and wife. … It is said that one night a robber broke into the Church but was so horrified at seeing the figure of Death in the moonlight that he dropped his crowbar and fled in terror. The crowbar was displayed for many years beside the monument but it no longer remains.”

Relative

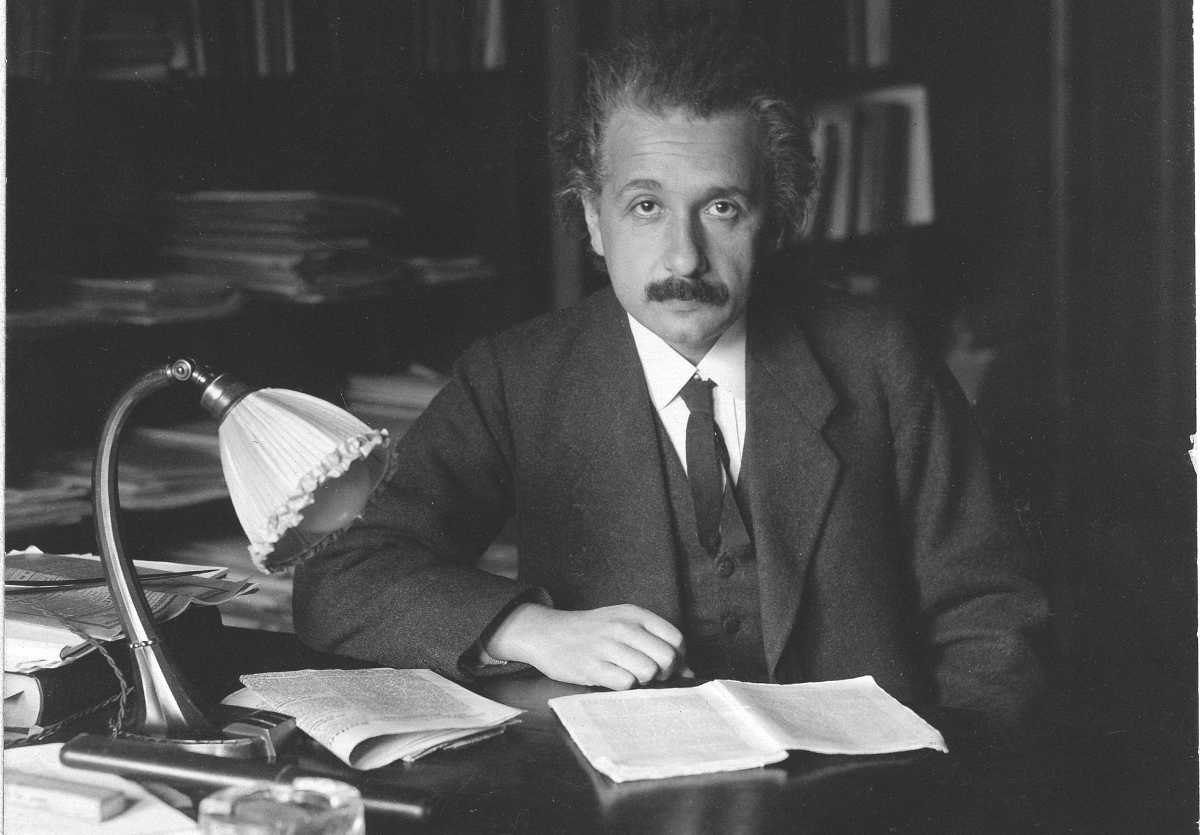

During an eclipse in 1919, Sir Arthur Eddington confirmed Albert Einstein’s prediction of the gravitational bending of light rays, upholding the general theory of relativity. That Christmas, Einstein wrote to his friend Heinrich Zangger in Zurich:

“With fame I become more and more stupid, which, of course, is a very common phenomenon. There is far too great a disproportion between what one is and what others think one is, or at least what they say they think one is. But one has to take it all with good humor.”

(From Helen Dukas and Banesh Hoffmann, eds., Albert Einstein, the Human Side: New Glimpses From His Archives, 1979.)

In a Word

sybotism

n. the tending of swine

The Seconds Pendulum

An interesting historical fact from these MIT notes: Christiaan Huygens proposed defining the meter conveniently as the length of a pendulum that produces a period of 2 seconds. A pendulum’s period is

so, using Huygens’ standard of T = 2s for 1 meter,

“So, if Huygens’s standard were used today, then g would be π2 by definition.”

Crossing

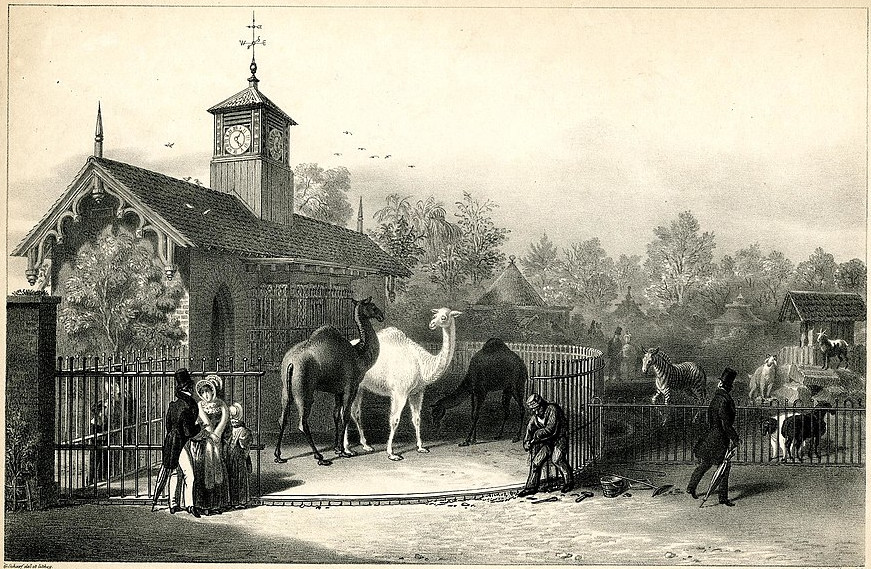

For whatever this is worth: In Samuel Butler’s semi-autobiographical novel The Way of All Flesh, “one of the most eminent doctors in London” cures young Ernest Pontifex of nervous prostration by a course of “crossing,” or change. “Crossing is the great medical discovery of the age. Shake him out of himself by shaking something else into him”:

I have found the Zoological Gardens of service to many of my patients. I should prescribe for Mr Pontifex a course of the larger mammals. Don’t let him think he is taking them medicinally, but let him go to their house twice a week for a fortnight, and stay with the hippopotamus, the rhinoceros, and the elephants, till they begin to bore him. I find these beasts do my patients more good than any others. The monkeys are not a wide enough cross; they do not stimulate sufficiently. The larger carnivora are unsympathetic. The reptiles are worse than useless, and the marsupials are not much better. Birds again, except parrots, are not very beneficial; he may look at them now and again, but with the elephants and the pig tribe generally he should mix just now as freely as possible.

“Had the doctor been less eminent in his profession I should have doubted whether he was in earnest, but I knew him to be a man of business who would neither waste his own time nor that of his patients,” writes Butler’s narrator. “As soon as we were out of the house we took a cab to Regent’s Park, and spent a couple of hours in sauntering round the different houses. Perhaps it was on account of what the doctor had told me, but I certainly became aware of a feeling I had never experienced before. I mean that I was receiving an influx of new life, or deriving new ways of looking at life — which is the same thing — by the process. I found the doctor quite right in his estimate of the larger mammals as the ones which on the whole were most beneficial, and observed that Ernest, who had heard nothing of what the doctor had said to me, lingered instinctively in front of them. As for the elephants, especially the baby elephant, he seemed to be drinking in large draughts of their lives to the re-creation and regeneration of his own.

“We dined in the gardens, and I noticed with pleasure that Ernest’s appetite was already improved. Since this time, whenever I have been a little out of sorts myself I have at once gone up to Regent’s Park, and have invariably been benefited. I mention this here in the hope that some one or other of my readers may find the hint a useful one.”

Consequences

Dutch Anabaptist Dirk Willems had made good his escape from prison in 1569 when a pursuing guard fell through the ice of a frozen pond and called for help.

Willems turned back to rescue him and was recaptured, tortured, and executed.

Progress

“Wherever there is a phonograph the musical instrument is displaced. The time is coming when no one will be ready to submit himself to the ennobling discipline of learning music. Everyone will have their ready-made or ready-pirated music in their cupboards.”

— John Philip Sousa, New York Morning Telegraph, June 12, 1906

Podcast Episode 342: A Slave Sues for Freedom

In 1844 New Orleans was riveted by a dramatic trial: A slave claimed that she was really a free immigrant who had been pressed into bondage as a young girl. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll describe Sally Miller’s fight for freedom, which challenged notions of race and social hierarchy in antebellum Louisiana.

We’ll also try to pronounce some drug names and puzzle over some cheated tram drivers.