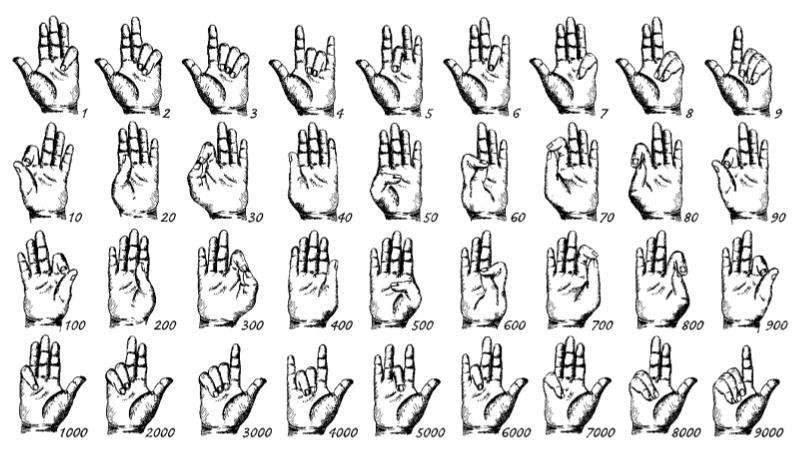

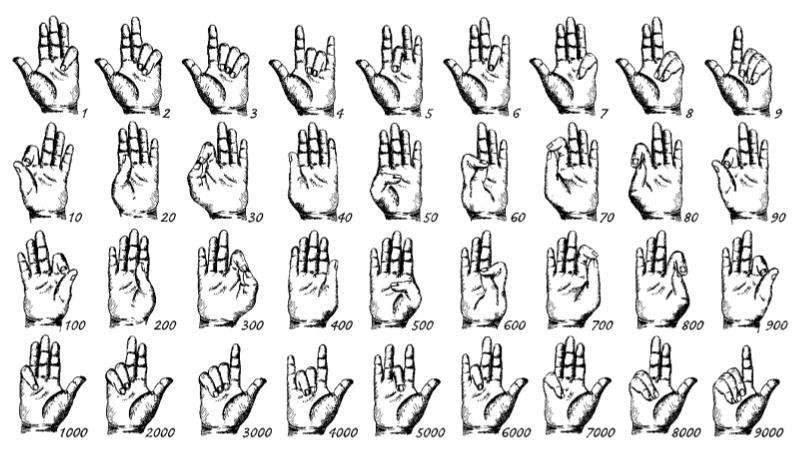

Writing in the north of England in the early 8th century, the Venerable Bede described a Roman system of finger counting:

1 = the little finger bent at the middle joint

2 = the ring and little fingers bent at the middle joints

3 = the middle, ring, and little fingers bent at the middle joints

4 = the middle and ring fingers bent at the middle joints

5 = the middle finger only bent at the middle joint

6 = the ring finger bent at the middle joint

7 = the little finger closed on the palm

8 = the ring and little fingers closed on the palm

9 = the middle, ring, and little fingers closed on the palm

10 = the tip of the index finger touching the middle joint of the thumb

11 to 19 = the actions denoting each numeral from 1 to 9 plus that of 10

20 = the thumb tucked between the index and middle fingers, so that the thumbnail touches the middle joint of the index finger

21 to 29 = the actions denoting each numeral from 1 to 9 plus that of 20

30 = the tips of the thumb and index finger touching and forming a circle or ring

40 = the thumb and index finger standing erect and close together

50 = the thumb bent at both joints and held against the palm

60 = the index finger closed over the thumb

70 = the first joint of the index finger resting over the first joint of the thumb, which is held nearly straight

80 = the tip of the index finger resting on the first joint of the thumb

90 = the thumb bent over the first joint of the index finger

The signs for 100, 200, 300, and so on are the same as 10, 20, 30, but made by the right hand; and the signs for 1,000, 2,000, 3,000 and so on are the same as 1, 2, 3 but made by the right hand. “To add two numbers, one simply signed the first, then made the mental arithmetical calculation and reproduced the gesture corresponding with the correct sum,” writes Angus Trumble in The Finger: A Handbook (2010). “The process was cumulative; to add a further number to the sum of the first two, you proceeded to represent the gesture corresponding with the new total, and so on. Likewise, the task of subtraction merely threw the whole system into reverse. It was perfectly clear to anyone observing you carry out these separate procedures whether the job in hand was one of addition or subtraction.”

Trumble says that at the end of the 19th century Wallachian peasants were discovered to have preserved a few methods of digital multiplication and division that had been preserved throughout the Roman empire. Here’s one.