“One can pay back the loan of gold, but one lies forever in debt to those who are kind.” — Marcus Aurelius

Sickness and Health

What most clinicians do when they receive a laboratory report is, of course, to look up the normal range for the tests in question. … Traditionally, a normal range is calculated in such a way that it includes 95% of the results found in a group of normal or healthy persons, and, consequently, there is a 5% risk that a healthy person will present with an abnormal laboratory result. Then, imagine that you do ten tests on a normal person. In that case the risk that at least one of these tests is abnormal is (1 – 0.9510) which amounts to 0.40 or 40%. If you do twenty-five tests (and that is not uusual in clinical practice), this chance is 72%! As Edmond A. Murphy puts it so aptly, ‘Therefore, a normal person is anyone who has not been sufficiently investigated.’

— Henrik R. Wulff, Stig Andur Pedersen, and Raben Rosenberg, Philosophy of Medicine: An Introduction, 1990, citing Murphy’s The Logic of Medicine, 1976

Ape Talk

Edgar Rice Burroughs invented an extensive vocabulary for the Mangani, the great apes of the Tarzan novels:

afraid: utor

baboon: tongani

branch: balu-den

cave: zu-kut

country: pal

elephant: tantor

hair: b’zan

hate: ugla

jackal: ungo

lightning: ara

look: yato

love: gree-ah

mother: kalu

rhinoceros: buto

strong: zu-vo

valley: pele

water: lul

Tarzan supposed that Mangani might be the basis for the language of all creatures, because all the animals of the jungle understood it to some extent. “It sounds to man like growling and barking and grunting, punctuated at times by shrill screams, and it is practically untranslatable to any tongue known to man,” Burroughs wrote in Tarzan at the Earth’s Core.

I’m getting this from David Ullery’s The Tarzan Novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs, but there are many online dictionaries. French writer Jacques Jouet even composed a love poem in the language.

Related: In reading English books Tarzan learned to grasp each word in its entirety, but in speaking them aloud he would spell them using the names he’d invented for the letters, according to Jungle Tales of Tarzan. “Thus it was an imposing word which Tarzan made of GOD. The masculine prefix of the apes is BU, the feminine MU; g Tarzan had named LA, o he pronounced TU, and d was MO. So the word God evolved itself into BULAMUTUMUMO, or, in English, he-g-she-o-she-d.”

A Spider’s World

Spiders are largely blind but experience the world through vibrations in their webs, which they detect with their legs. Now MIT materials scientist Markus Buehler has created a musical impression of that experience. His team made three-dimensional maps of the webs of tropical tent-web spiders, identified the vibrating frequency of each thread, and converted these frequencies into ranges that humans can hear. Threads that are closer to the spider sound louder in the recording.

“The spider web can be viewed as an extension of the body of the spider, in that it lives within it, but also uses it as a sensor,” Buehler told New Scientist. “When you go into the virtual reality world and you dive inside the web, being able to hear what’s going on allows you to understand what you see.”

(Thanks, Colin.)

Advice

Either know, or listen to someone who does. You can’t live without understanding, whether your own or someone else’s. There are many, however, who don’t know that they don’t know, and others who think they know, but don’t. Stupidity’s faults are incurable, for since the ignorant don’t know what they are, they don’t search for what they lack. Some individuals would be wise if they didn’t believe that they already were. Given all this, although oracles of good sense are rare, they sit idle, because nobody consults them. Seeking advice will neither diminish your greatness nor refute your ability. In fact, it will enhance your reputation. Engage with reason so misfortune doesn’t contend with you.

— Baltasar Gracián, The Pocket Oracle and Art of Prudence, 1647

Memorial

When Sarah Davis of Hiawatha, Kansas, died in 1930, her husband John spent most of his wealth on her grave, including 11 life-size statues of Italian marble consorting under a canopy that weighs 50 tons.

The extravagance won John some criticism during the Depression, but today the monument brings a steady flow of tourists to the town.

Viewpoint

Leonardo noted that studies of shadow appeal to the same geometric laws as those of perspective — “in matters perspectival, a light source is no different from the eye [… since] the visual ray is similar to the shadowy ray in terms of speed and converging lines.” Just as perspective considers a scene as regarded from a particular point of view, a shadow is a record of what “the lamp cannot see.”

Philosopher Roberto Casati writes, “This is a strong analogy. There is shadow where the light cannot see. Indeed, shadow is exactly what the light source cannot see. A lamp sees only the things that it illuminates; objects in shadow are behind lighted objects that screen the shadow from the lamp’s perspective. For this same reason, when we examine a shadow, we discover the profile of things from the point of view of the lamp. … Shadow allows us to see a point of view other than our own without even getting up from our seats.”

(From Casati’s Shadows, 2000, via Marko Uršič, Shadows of Being: Four Philosophical Essays, 2019.)

Throughput

A bedeviling little puzzle from Dickinson College mathematician David Richeson.

A topologist, it is said, is someone who can’t tell his donut from his coffee mug.

Art and Commerce

Before the 19th century, containers did not come in standard sizes, and students in the 1400s were taught to “gauge” their capacity as part of their standard mathematical education:

There is a barrel, each of its ends being 2 bracci in diameter; the diameter at its bung is 2 1/4 bracci and halfway between bung and end it is 2 2/9 bracci. The barrel is 2 bracci long. What is its cubic measure?

This is like a pair of truncated cones. Square the diameter at the ends: 2 × 2 = 4. Then square the median diameter 2 2/9 × 2 2/9 = 4 76/81. Add them together: 8 76/81. Multiply 2 × 2 2/9 = 4 4/9. Add this to 8 76/81 = 13 31/81. Divide by 3 = 4 112/243 … Now square 2 1/4 = 2 1/4 × 2 1/4 = 5 1/16. Add it to the square of the median diameter: 5 5/16 + 4 76/81 = 10 1/129. Multiply 2 2/9 × 2 1/4 = 5. Add this to the previous sum: 15 1/129. Divide by 3: 5 1/3888. Add it to the first result: 4 112/243 + 5 1/3888 = 9 1792/3888. Multiply this by 11 and then divide by 14 [i.e. multiply by π/4]: the final result is 7 23600/54432. This is the cubic measure of the barrel.

Interestingly, this practice informed the art of the time — this exercise is from a mathematical handbook for merchants by Piero della Francesca, the Renaissance painter. Because many artists had attended the same lay schools as business people, they could invoke the same mathematical training in their work, and visual references that recalled these skills became a way to appeal to an educated audience. “The literate public had these same geometrical skills to look at pictures with,” writes art historian Michael Baxandall. “It was a medium in which they were equipped to make discriminations, and the painters knew this.”

(Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy, 1988.)

04/10/2021 UPDATE: A reader suggests that there’s a typo in the original reference here. If 9 1792/3888 is changed to 9 1793/3888, the final result is 7 23611/54432, which is exactly the result obtained by integration using the approximation π = 22/7. (Thanks, Mariano.)

In a Word

imperspicable

adj. that cannot be seen or discerned; invisible

acerbate

v. embitter

resarciate

v. to make amends for, compensate for

ultion

n. revenge

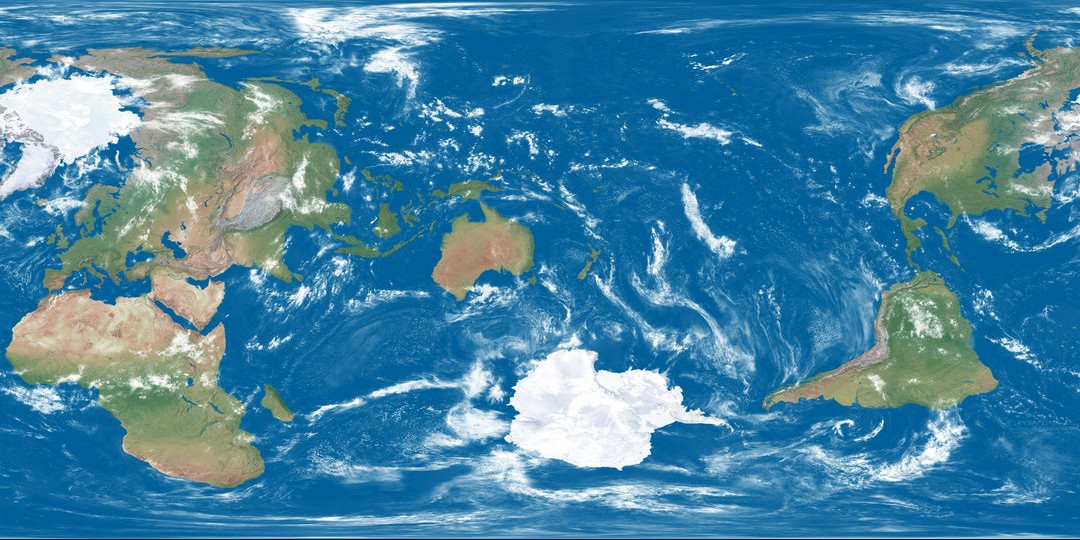

From geographer Simon Kuestenmacher: a world map centered on New Zealand.

Also: Maps without New Zealand, maps with New Zealand, maps with too much New Zealand.