A puzzle by Tim C., an applied research mathematician at the National Security Agency, from the agency’s January 2017 Puzzle Periodical:

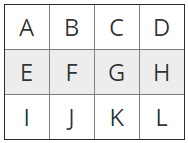

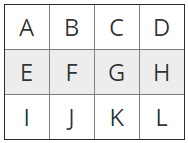

Alice has a dozen cartons, arranged in a 3×4 grid, which for convenience we have labeled A through L:

She has randomly chosen two of the cartons and hidden an Easter egg inside each of them, leaving the remaining ten cartons empty. She gives the dozen cartons to Bob, who opens them in the order A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L until he finds one of the Easter eggs, whereupon he stops. The number of cartons that he opens is his score. Alice then reseals the cartons, keeping the eggs where they are, and presents the cartons to Chris, who opens the cartons in the order A, E, I, B, F, J, C, G, K, D, H, L, again stopping as soon as one of the Easter eggs is found, and scoring the number of opened cartons. Whoever scores lower wins the game; if they score the same then it’s a tie.

For example, suppose Alice hides the Easter eggs in cartons H and K. Then Bob will stop after reaching the egg in carton H and will score 8, while Chris will stop after reaching the egg in carton K and will score 9. So Bob wins in this case.

Who is more likely to win this game, Bob or Chris? Or are they equally likely to win?

|

SelectClick for Answer |

Bob is more likely to win.

Label a carton with a “b” (respectively, a “c”) if Bob (respectively, Chris) reaches that carton more quickly, and also record Bob’s (respectively, Chris’s) score upon reaching that carton. Label cartons A and L with “xx” since both players reach those cartons simultaneously.

We obtain:

xx b2 b3 b4

c2 c5 b7 b8

c3 c6 c9 xx

Note that there are five b cartons and five c cartons. So the cases in which Alice selects carton A or carton L are equally split between Bob and Chris. Similarly if Alice selects two b cartons then Bob necessarily wins, but these are balanced out by an equal number of cases in which Alice selects two c cartons and C necessarily wins.

The crucial cases occur when Alice selects one b carton and one c carton. Bob wins if the b carton has a lower score than the c carton:

b2 and (c3 or c5 or c6 or c9)

b3 and (c5 or c6 or c9)

b4 and (c5 or c6 or c9)

b7 and c9

b8 and c9

Chris wins if the c carton has a lower score than the b carton:

c2 and (b3 or b4 or b7 or b8)

c3 and (b4 or b7 or b8)

c5 and (b7 or b8)

c6 and (b7 or b8)

Since this yields 12 cases in Bob’s favor and only 11 cases in Chris’s favor, Bob has the advantage.

|