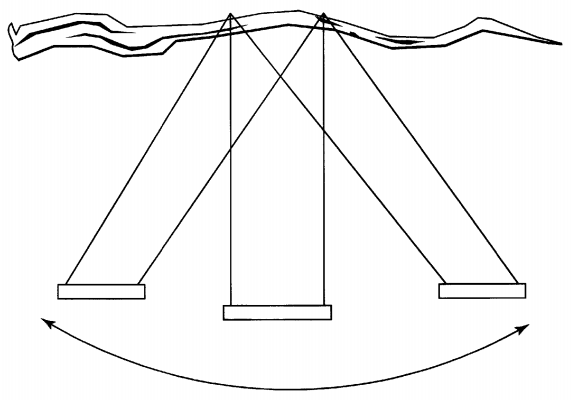

In 2002 a 7-year-old boy, Steven Olson, patented a “method of swinging on a swing”:

The method comprises the steps of: a) positioning a user on the seat; and b) having the user pull alternately on one chain to induce movement of the user and the swing toward one side, and then on the other chain to induce movement of the user and the swing toward the other side, to create side-to-side motion.

Steven’s father, Peter, a patent attorney, wanted to show him how the system works. Steven’s submission was approved at first (the patent office said that its technical definition of obviousness “is not necessarily the conventional definition”) but later reconsidered and invalidated, perhaps due to criticism.

A year earlier, to test the workability of a new national patent system, an Australian man had patented the wheel.