Here are seven new lateral thinking puzzles — play along with us as we try to untangle some perplexing situations using yes-or-no questions.

Here are seven new lateral thinking puzzles — play along with us as we try to untangle some perplexing situations using yes-or-no questions.

Antebellum social theorist George Fitzhugh argued that slavery should be extended to whites. “It is a libel on white men to say they are unfit for slavery,” he wrote. “Catch them young, train, domesticate, and civilize them, and they would make as faithful and valuable servants as those indentured servants which our colonial ancestors bought in such large numbers from England.”

He thought that capitalism inevitably creates social inequality, and that those whom it oppresses can best be helped by subjugating them. “The whole war against slavery, has grown out of the hatred of the white to the black,” he wrote. “Nobody ever proposed to abolish white slavery, or the white slave trade. … Nobody ever proposed to abolish any other than negro slavery, and if we could buy Yankees for house-servants, and confine the negroes to field work, all this abolition strife would cease.”

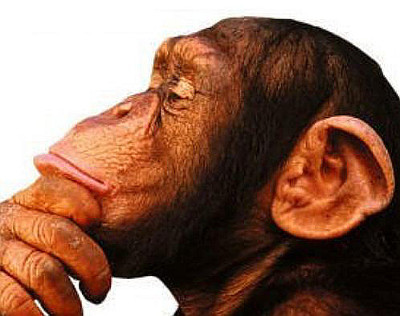

Lee Sallows just sent me this — the puzzle is difficult, but the solution is stunning:

What’s remarkable about this set of words?

BIOLOGY DEATHLY SLOSHED BASTARD SELVAGE FISSILE DALLIES FLAVORS

TO THE PATRIOTIC UNMARRIED LADIES. — I am a soldier, just returned from the wars. Have lost a leg, but expect to get a cork one; have a useless arm, but will be called brave for it; was once good-looking, but am now scarred all over. If any patriotic young lady will marry me, why fall in line! The applicant must be moderately handsome, have an excellent education, play on the piano and sing; and a competency will not be objectionable. One with these requirements would, doubtless, secure my affections. Address Capt. F.A.B., MERCURY Office.

— New York Sunday Mercury, Nov. 9, 1862

In 18 years and 5 months (May 1810 to October 1828), Franz Schubert composed more than 1,000 works. And that’s counting complex pieces, such as operas, suites of dances for piano or orchestra, and song cycles numbering up to 24 individual items, as single compositions. From Harold Schonberg’s Lives of the Great Composers:

[Leopold von] Sonnleithner reports that ‘at Fräulein Fröhlich’s request, Franz Grillparzer had written for the occasion the beautiful poem Ständchen, and this she gave to Schubert, asking him to set it to music as a serenade for her sister Josefine (mezzo-soprano) and women’s chorus. Schubert took the poem, went into an alcove by the window, read it through carefully a few times and then said with a smile, “I’ve got it already, it’s done, and it’s going to be quite good.”‘ [Joseph von] Spaun tells of the composition of the Erlkönig. He and [Johann] Mayrhofer visited Schubert and found him reading the poem. ‘He paced up and down several times with the book, suddenly he sat down, and in no time at all (just as quickly as you can write) there was the glorious ballad finished on the paper. We ran with it to the Seminary, for there was no piano at Schubert’s, and there, on the very same evening, the Erlkönig was sung and enthusiastically received.’

When he worked, he worked feverishly. The poet Franz von Schober said, “If you go to see him during the day, he says ‘Hello, how are you? — Good!’ and goes on working, whereupon you go away.”

In April 1909, Carl Jung asked Sigmund Freud his opinion on precognition and parapsychology. As Freud was dismissing them, Jung felt “a curious sensation”:

It was as if my diaphragm was made of iron and was becoming red-hot — a glowing vault. And at that moment there was such a loud report in the bookcase, which stood right next to us, that we both started up in alarm, fearing the thing was going to topple over us. I said to Freud: ‘There, that is an example of a so-called catalytic exteriorisation phenomenon.’

‘Oh come,’ he exclaimed. ‘That is sheer bosh.’

‘It is not,’ I replied. ‘You are mistaken, Herr Professor. And to prove my point I now predict that in a moment there will be another loud report!’ Sure enough, no sooner had I said the words than the same detonation went off in the bookcase.

“To this day I do no know what gave me this certainty,” Jung said later. “But I knew beyond all doubt that the report would come again. Freud only stared aghast at me. I do not know what was in his mind, or what his look meant. In any case, this incident aroused his mistrust of me, and I had the feeling that I had done something against him. I never afterwards discussed the incident with him.”

Freud was not impressed. In a letter to Jung he wrote, “At first I was inclined to ascribe some meaning to it if the noise we heard so frequently when you were here were never again heard after your departure. But since then it has happened over and over again, yet never in connection with my thoughts and never when I was considering you or your special problem.”

A fuller account is here. It’s not clear that they ever discovered the source of the sound, but note that Freud’s letter was written in the same month as the experience, where Jung’s recollection was made in an interview half a century later — when (perhaps among other things) he had misremembered the location of the bookshelf.

1

1 1

1 0 1

1 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 9 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 9 9 9 9 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 9 2 9 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 9 9 9 9 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 9 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 0 1

1 0 0 1

1 0 1

1 1

1

Amazingly, this is a prime number. When the digits are assembled into one long string, beginning at the top of the star and reading each row left to right, they form a 1093-digit number whose only factors are 1 and itself.

It was discovered by Australian mathematician Michael Hartley. See more of his prime curios.

In the 1930s Colgate University psychologist Harvey Fitz-Gerald interviewed 254 “men and women of eminence,” asking them to describe memories that had been evoked by scent. One recalled:

On the train once, in the midst of happy conditions, I suddenly felt discouraged, awkward, unhappy. As soon as I recognized the perfume used by a fellow traveler, I saw very vividly a large dancing class, a French dancing master, and felt again my girlish dismay at his attitude toward my poor attempts to learn the steps he was trying to teach me. As soon as the memory picture came I knew why I had suddenly felt unhappy, and, of course, came back to normal. This experience occurred some fifteen or twenty years after the last time I had seen the dancing master.

Another recalled a strange feeling of loneliness that had come over her while reading a book at the age of 25. She found that it had been printed in England, whence all of her childhood books had come. Laird wrote, “It will be found interesting, the next time an unexpected memory or thought ‘pops into your head,’ … to think back over the air-borne fragrances and odors which may have given these changes their start.”

(Donald A. Laird, “What Can You Do With Your Nose?”, The Scientific Monthly 41:2 [1935], 126-130.)

Irish physician Henry Marsh addressed an odd phenomenon in 1842: patients who glow in the dark. Shortly after one of his patients had died of tuberculosis, he’d received a letter from her sister:

‘About an hour and a half before my dear sister’s death, we were struck by a luminous appearance proceeding from her head in a diagonal direction. … The light was pale as the moon; but quite evident to mamma, myself, and sister, who were watching over her at the time. One of us at first thought it was lightning, till shortly after we fancied we perceived a sort of tremulous glimmer playing round the head of the bed; and then recollecting we had read something of a similar nature having been observed previous to dissolution, we had candles brought into the room, fearing our dear sister would perceive it, and that it might disturb the tranquillity of her last moments.’

A colleague, Dublin heart specialist William Stokes, described a breast cancer from which “a quantity of luminous fluid was constantly poured out”:

‘Upon being asked whether she suffered much pain, [the patient] answered, “Not now, Sir, but I cannot sleep watching this sore which is on fire every night.” I directed that she should send for me whenever she perceived the luminous appearance, and on that night I was summoned between ten and eleven o’clock. The lights in the ward having been then extinguished, she was sitting leaning forward, the left hand supporting the tumour, while with the right she every now and then lifted up the covering of the ulcer to gaze on this, to her, supernatural appearance. The whole of the base and the edges of the cavity phosphoresced in the strongest manner.’

Sir Henry speculated that the luminescence might have been caused by phosphorous, but “elemental phosophorous is far too reactive to be produced naturally by the human body,” writes Thomas Morris in The Mystery of the Exploding Teeth, his 2018 exploration of medical curiosities. He speculates that luminous bacteria, while also unlikely, might offer one explanation.

(Henry Marsh, “On the Evolution of Light From the Living Human Subject,” Provincial Medical Journal and Retrospect of the Medical Sciences 4:88 [1842], 163.)