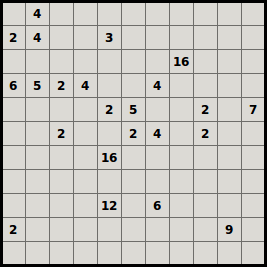

Japanese publisher Nikoli produces this geometric logic puzzle. Can you divide this grid into rectangular and square pieces such that each piece contains exactly one number and each number reflects its piece’s area?

Japanese publisher Nikoli produces this geometric logic puzzle. Can you divide this grid into rectangular and square pieces such that each piece contains exactly one number and each number reflects its piece’s area?

English philanthropist Lady Jane Stanley financed footpaths through her native Knutsford with an odd proviso:

For some unknown reason Lady Jane disliked to see men and women linked together, i.e. walking arm in arm; and in her donations for the pavement of the town, provided that a single flag in breadth should be the limit of her generosity,– but she did not specify how broad the single flag was to be, and I fear her wishes are evaded, and the disapproved linking together often indulged in: the chief security for her order being observed is the disagreeable fact that in many places the streets and consequently the raised pavements are too narrow to allow of more than a very slender foot-path, so that if the lasses occupy the flags, the swains must either walk behind, or pick their way in the channel.

Never married, she composed her own epitaph:

A maid I lived,– a maid I died,–

I never was asked,– and never denied.

(From Henry Green, Knutsford, Its Traditions and History, 1859.)

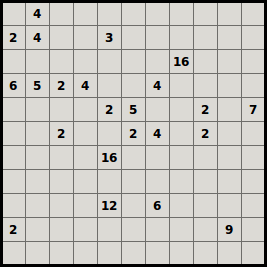

John Hornby left a privileged background in England to roam the vast subarctic tundra of northern Canada. There he became known as “the hermit of the north,” famous for staying alive in a land with very few resources. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast, we’ll spend a winter with Hornby, who’s been called “one of the most colorful adventurers in modern history.”

We’ll also consider an anthropologist’s reputation and puzzle over an unreachable safe.

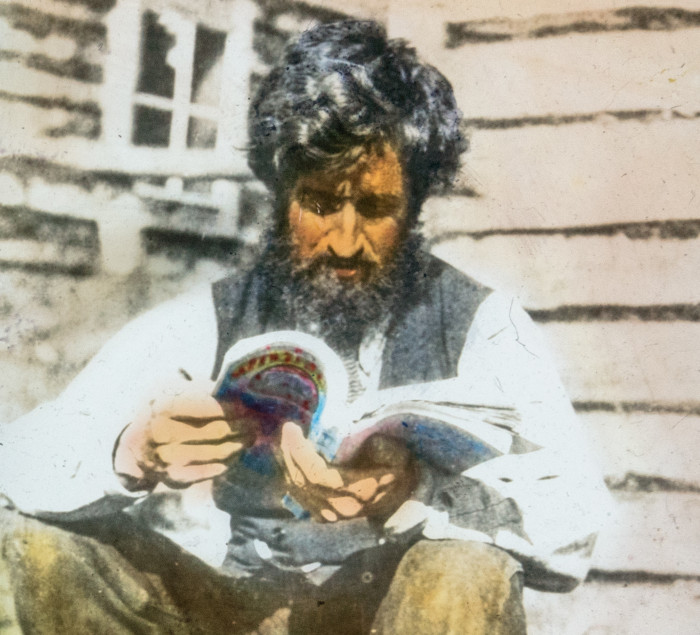

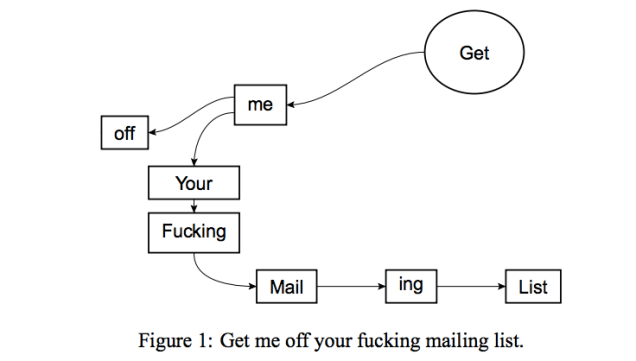

In 2014, after receiving dozens of unsolicited emails from the International Journal of Advanced Computer Technology, scientists David Mazières and Eddie Kohler submitted a paper titled “Get Me Off Your Fucking Mailing List.”

To Mazières’ surprise, “It was accepted for publication. I pretty much fell off my chair.”

The acceptance bolsters the authors’ contention that IJACT is a predatory journal, an indiscriminate but superficially scholarly publication that subsists on editorial fees. Mazières said, “They told me to add some more recent references and do a bit of reformatting. But otherwise they said its suitability for the journal was excellent.”

He didn’t pursue it. And, at least as of 2014, “They still haven’t taken me off their mailing list.”

The Beggar’s Opera, by John Gay, premiered in 1728 at the Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre, managed by John Rich.

It was an enormous success, becoming one of the most popular plays of the 18th century.

This “had the effect, as was ludicrously said, of making Gay rich and Rich gay.”

(From Johnson’s Lives of the Poets.)

Every farmer who owns a donkey beats it. The pronoun it in this sentence seems to have a clear meaning. But does it? Normally the phrase a donkey refers to some particular donkey; the indefinite article a refers to something that exists. But here its meaning is more abstract — a donkey seems to refer to a whole class of unfortunate donkeys. And in that case the pronoun it seems to have nothing to point to.

Yet most readers have no trouble understanding the sentence. How?

In 1997, Berkeley psychology student Arthur Aron and his colleagues refined a list of 36 questions for “creating closeness.” “One key pattern associated with the development of a close relationship among peers is sustained, escalating, reciprocal, personal self-disclosure,” Aron wrote. “The core of the method we developed was to structure such self-disclosure between strangers.”

Each pair of subjects took turns asking each other questions from this list, in order:

Most of the pairs of strangers left the session with highly positive feelings for each other: “[I]mmediately after about 45 min of interaction, this relationship is rated as closer than the closest relationship in the lives of 30% of similar students” (though, to be sure, “it seems unlikely that the procedure produces loyalty, dependence, commitment, or other relationship aspects that might take longer to develop”).

(Arthur Aron et al., “The Experimental Generation of Interpersonal Closeness: A Procedure and Some Preliminary Findings,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 23:4 [1997], 363-377.)

In 1757 Ben Franklin revealed “How to make a Striking Sundial, by which not only a Man’s own Family, but all his Neighbours for ten Miles round, may know what o’Clock it is, when the Sun shines, without seeing the Dial”:

Chuse an open Place in your Yard or Garden, on which the Sun may shine all Day without any Impediment from Trees or Buildings. On the Ground mark out your Hour Lines, as for a horizontal Dial, according to Art, taking Room enough for the Guns. On the Line for One o’Clock, place one Gun; on the Two o’Clock Line two Guns, and so of the rest. The Guns must all be charged with Powder, but Ball is unnecessary. Your Gnomon or Style must have twelve burning Glasses annex’d to it, and be so placed as that the Sun shining through the Glasses, one after the other, shall cause the Focus or burning Spot to fall on the Hour Line of One for Example, at one a Clock, and there kindle a Train of Gunpowder that shall fire one Gun. At Two a Clock, a Focus shall fall on the Hour Line of Two, and kindle another Train that shall discharge two Guns successively; and so of the rest.

Note, There must be 78 Guns in all. Thirty-two Pounders will be best for this Use; but 18 Pounders may do, and will cost less, as well as use less Powder, for nine Pounds of Powder will do for one Charge of each eighteen Pounder, whereas the Thirty-two Pounders would require for each Gun 16 Pounds.

Note also, That the chief Expence will be the Powder, for the Cannon once bought, will, with Care, last 100 Years.

Note moreover, That there will be a great Saving of Powder in cloudy Days.

(From Poor Richard Improved. He was mocking a class of overambitious amateur experimenters called virtuosi. “Kind Reader, Methinks I hear thee say, That it is indeed a good Thing to know how the Time passes, but this Kind of Dial, notwithstanding the mentioned Savings, would be very expensive; and the Cost greater than the Advantage. Thou art wise, my Friend, to be so considerate beforehand; some Fools would not have found out so much, till they had made the Dial and try’d it. Let all such learn that many a private and many a publick Project, are like this Striking Dial, great Cost for little Profit.”)

Tiny but interesting: The Beatles’ 1995 song “Free as a Bird” was based on a home demo that John Lennon had recorded in 1977, three years before his murder. After the surviving Beatles had added their own parts, they appended a music-hall-style ukulele to the end, followed by a spoken snippet by Lennon, “Turned out nice again,” a reference to entertainer George Formby.

In Beatles style they reversed this snippet, expecting it to sound like cryptic nonsense. Instead, the result (arguably) sounds like “Made by John Lennon.”

Paul McCartney said, “None of us had heard it when we compiled it, but when I spoke to the others and said, ‘You’ll never guess,’ they said, ‘We know, we’ve heard it too.’ And I swear to God he definitely says it. We could not in a million years have known what that phrase would be backwards.”

(From Peter Ames Carlin’s Paul McCartney: A Life, 2009.)