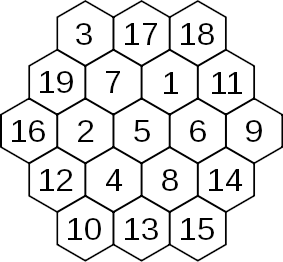

There’s only one normal magic hexagon — only one hexagonal arrangement of cells like the one shown here that can be filled with the consecutive integers 1 to n such that every row, in all three directions, sums to the same total. (This excludes the trivial example of a single cell on its own, as well as rotations and reflections of the hexagon shown here.)

Amazingly, it appears that this lonely example may not have been discovered until 1888! In a 1988 letter to the Mathematical Gazette, Martin Gardner reported that the magic hexagon was given as a problem in the German magazine Zeitschrift für mathematischen und naturwissenschaftlichen Unterricht (Volume 19, page 429) in 1888. The proposer was identified only as von Haselberg, of Stralsund; his solution was published in the next volume.

Gardner writes, “The structure could easily have been discovered by mathematicians in ancient times, but as of now, this is the earliest known publication.”

(Martin Gardner, “The History of the Magic Hexagon,” Mathematical Gazette 72:460 [June 1988], 133.)