The English name for 13,000,000,000,000,000,003,019,000,000,000, THIRTEEN NONILLION THREE TRILLION NINETEEN BILLION, is spelled with 1 B, 2 Hs, 3 Rs, 4 Os, 5 Ts, 6 Ls, 7 Es, 8 Is, and 9 Ns.

(Thanks, David.)

The English name for 13,000,000,000,000,000,003,019,000,000,000, THIRTEEN NONILLION THREE TRILLION NINETEEN BILLION, is spelled with 1 B, 2 Hs, 3 Rs, 4 Os, 5 Ts, 6 Ls, 7 Es, 8 Is, and 9 Ns.

(Thanks, David.)

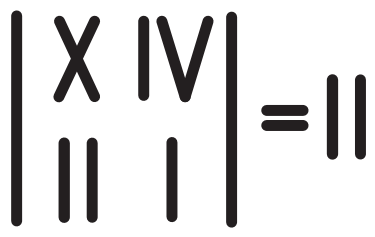

On a glass door in the mathematics department at the University of Erlangen–Nürnberg in Germany, this determinant is printed:

Sure enough, X · I – IV · II = II.

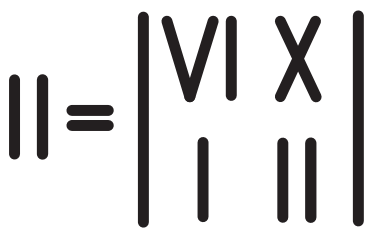

Pass through the door and regard it from the other side and you see a different equation:

But this too is true: II = VI · II – X · I.

(Burkard Polster, “Mathemagical Ambigrams,” Proceedings of the Mathematics and Art Conference, 2000.)

An honest number is a number n that can be described using exactly n letters. For example, 8 can be described as TWO CUBED, and 11 as TWO PLUS NINE.

In 2003, Bill Clagett found that

EIGHTEENTH ROOT OF EIGHT HUNDRED EIGHTY-FOUR QUATTUORDECILLION THREE HUNDRED THIRTY-FOUR TREDECILLION SIX HUNDRED EIGHTY DUODECILLION EIGHT HUNDRED TWENTY-SIX UNDECILLION SIX HUNDRED FIFTY-THREE DECILLION SIX HUNDRED THIRTY-SEVEN NONILLION ONE HUNDRED THREE OCTILLION NINETY SEPTILLION NINE HUNDRED EIGHTY-TWO SEXTILLION FIVE HUNDRED EIGHTY-ONE QUINTILLION FOUR HUNDRED FORTY-EIGHT QUADRILLION SEVEN HUNDRED NINETY-FOUR TRILLION NINE HUNDRED THIRTEEN BILLION FOUR HUNDRED THIRTY-TWO MILLION NINE HUNDRED FIFTY-NINE THOUSAND EIGHTY-ONE

contains 461 letters.

Beneath the charm-box is a small font. Each day every member of the family, in succession, enters the shrine room, bows his head before the charm-box, mingles different sorts of holy water in the font, and proceeds with a brief rite of ablution. The holy waters are secured from the Water Temple of the community, where the priests conduct elaborate ceremonies to make the liquid ritually pure.

— Horace Miner, “Body Ritual Among the Nacirema,” American Anthropologist, June 1956

(It’s satire. What’s Nacirema spelled backward?)

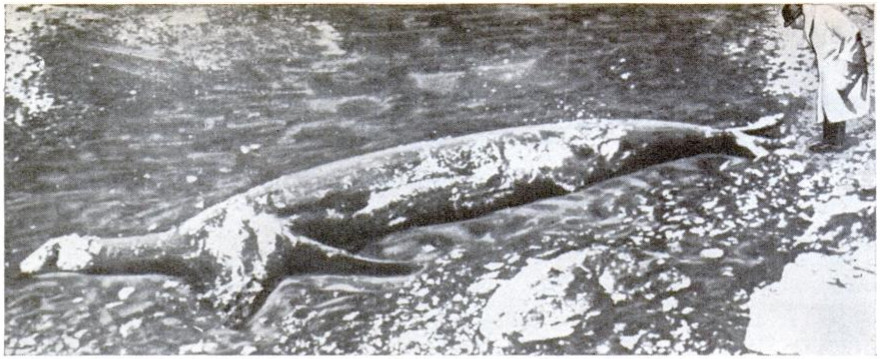

Something alarming washed up on a beach near Cherbourg in 1934 — a 25-foot carcass with a camel’s head, a three-foot neck, two shoulder fins, and a seal’s tail. Its bluish-gray skin was covered with what appeared to be fine white hairs, and its liver was 15 feet long.

Was it a sea serpent? A relative of the Loch Ness Monster? Probably not: A local biologist guessed that a whale had pursued herring into local waters and been killed by a liner.

Thirteen years later a 40-foot carcass washed up on the shore near Effingham on Vancouver Island, Canada. At first rumored to be the remains of Caddy, the sea serpent that supposedly haunts Cadboro Bay, it was later identified as a shark.

An optical illusion. All the edges in this image are straight, and each is either horizontal, vertical, or at a 45° angle.

Addressing communications to the post just for the pleasure of seeing whether the hard-worked authorities will be equal to deciphering them is perhaps not very considerate, but the officials are so very rarely found at fault that the laugh is almost always on their side. This phonographic postcard was delivered at the house of Mr. E.H. King, of Belle View House, Richmond, Surrey, who sent us the card within an hour and a half after he had posted it to himself locally.

That’s from the Strand, February 1899. “Phonographic” refers to a system of phonetic shorthand; this one must have been fairly well known if the G.P.O. deciphered it so quickly. Charles Dickens had to learn an early alphabetical shorthand for his work as a journalist; he adapted this later into a system of his own, some of which remains undeciphered.

During the Battle of Waterloo, a cannon shot struck the right leg of Henry Paget, Second Earl of Uxbridge, prompting this quintessentially British exchange:

Uxbridge: By God, sir, I’ve lost my leg!

Wellington: By God, sir, so you have!

That may be apocryphal, but the leg went on to a colorful career of its own.

The single most British conversation in the history of human civilization, in my judgment, took place on the Upper Nile in 1899, when starving explorer Ewart Grogan stumbled out of the bush and surprised one Captain Dunn, medical officer of a British exploratory expedition:

Dunn: How do you do?

Grogan: Oh, very fit thanks; how are you? Had any sport?

Dunn: Oh pretty fair, but there is nothing much here. Have a drink? You must be hungry; I’ll hurry on lunch.

“It was not until the two men had almost finished the meal that Dunn thought it excusable to enquire about the identity and provenance of his guest.”

In his 1986 commonplace book Hodgepodge, J. Bryan lists this as one of his favorite typographical errors:

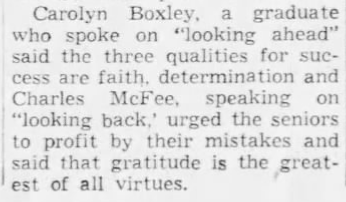

‘Carolyn B—-, who spoke on ‘Looking Ahead,’ said that the three qualities necessary for success are faith, determination and Charles McFee.

“I can’t classify it or explain it at all. I can only quote it.” I haven’t been able to find the original source.

09/17/2025 UPDATE: Reader Adam Mellion found it — it’s from the Richmond Times-Dispatch of June 12, 1954:

Not that striking when you see it in context. (Thanks, Adam.)