A thought experiment in probability by Leonardo Barichello: Two people are stranded on an island with only one banana to eat. To decide who gets it, they agree to play a game. Each of them will roll a fair 6-sided die. If the largest number rolled is a 1, 2, 3, or 4, then Player 1 gets the banana. If the largest number rolled is a 5 or 6, then Player 2 gets it. Which player has the better chance?

Black and White

For What It’s Worth

In a 2009 survey, readers of Stuttgarter Nachrichten, the largest newspaper in Stuttgart, chose Muggeseggele as the most beautiful word in Swabian German.

Muggeseggele means “the scrotum of a housefly.” It’s used ironically to describe a very small length.

Counting Sheep

Shepherds in Northern England used to tally their flocks using a base-20 numbering system. They’d count a score of sheep using the words:

Yan, tan, tether, mether, pip,

Azer, sayzer, acka, konta, dick,

Yanna-dick, tanna-dick, tethera-dick, methera-dick, bumfit,

Yanna-bum, tanna-bum, tethera-bum, methera-bum, jigget

… and then denote the completion of a group by taking up a stone or marking the ground before commencing the next count.

These systems vary by region — Wikipedia has them laid out in pleasing tables.

(Thanks, Brieuc.)

Underground Dining

Early visitors to Kenya’s Kitum Cave found the walls curiously scratched and furrowed: They discovered that elephants frequent the cave each night to scratch rocks from the walls, which they eat for their salt content.

They have done this for centuries, enlarging the cave significantly in the process and effectively converting it into a salt mine, which they now share with other species.

Medieval Music

In 2016, after 20 years of research, Cambridge University medieval music specialist Sam Barrett used the rediscovered leaf of an 11th-century manuscript to reconstruct music as it would have been heard a thousand years ago.

Melodies in those days were not recorded as precise pitches but relied on the memory of musicians and on aural traditions that died out in the 12th century. “We know the contours of the melodies and many details about how they were sung, but not the precise pitches that made up the tunes,” Barrett said. The missing leaf, appropriated by a Germanic scholar in 1840, contained vital neumes, or musical symbols, that allowed him and his colleagues to finish their reconstruction of Boethius’ “Songs of Consolation” as it was performed in the Middle Ages.

“There have been times while I’ve been working on this that I have thought I’m in the 11th century, when the music has been so close it was almost touchable,” Barrett said. “And it’s those moments that make the last 20 years of work so worthwhile.”

Secret Message

Jonathan Swift’s Journal to Stella, a collection of 65 letters written to his friend Esther Johnson, contains some puzzling passages, such as this one:

“He gave me al bsadnuk lboinlpl dfaonr ufainfbtoy dpionufnad, which I sent him again by Mr. Lewis.”

How should the obscured phrase be read?

Wildlife

In painting backdrops for the dioramas at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science in the 1970s, artist Kent Pendleton hid eight elves. “It was just kind of my own little private joke,” he said in 2018. “The first one was so small that hardly anyone could see it, but it sort of escalated over time, I guess. Some of the museum volunteers picked up on it and it developed a life of its own.”

The museum’s field guide currently lists nine hidden finds, but there are more — the exact number is not known.

Unquote

“The only way to keep ahead of the procession is to experiment. If you don’t, the other fellow will. When there’s no experimenting there’s no progress. Stop experimenting and you go backward. If anything goes wrong, experiment until you get to the very bottom of the trouble.” — Thomas Edison

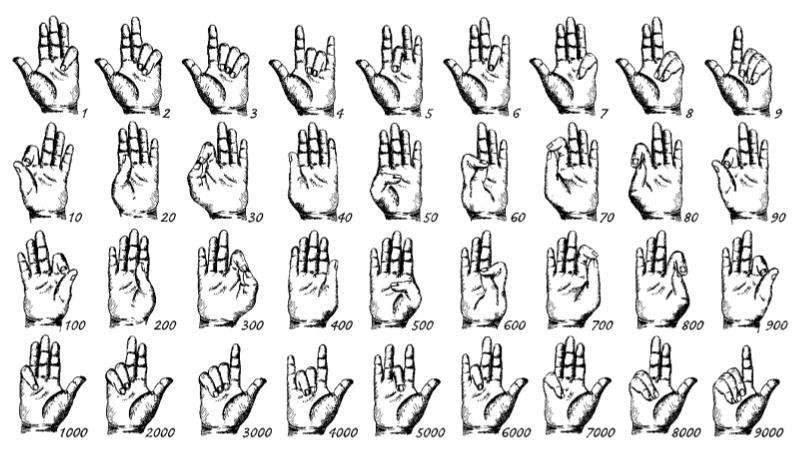

Finger Numerals

Writing in the north of England in the early 8th century, the Venerable Bede described a Roman system of finger counting:

1 = the little finger bent at the middle joint

2 = the ring and little fingers bent at the middle joints

3 = the middle, ring, and little fingers bent at the middle joints

4 = the middle and ring fingers bent at the middle joints

5 = the middle finger only bent at the middle joint

6 = the ring finger bent at the middle joint

7 = the little finger closed on the palm

8 = the ring and little fingers closed on the palm

9 = the middle, ring, and little fingers closed on the palm

10 = the tip of the index finger touching the middle joint of the thumb

11 to 19 = the actions denoting each numeral from 1 to 9 plus that of 10

20 = the thumb tucked between the index and middle fingers, so that the thumbnail touches the middle joint of the index finger

21 to 29 = the actions denoting each numeral from 1 to 9 plus that of 20

30 = the tips of the thumb and index finger touching and forming a circle or ring

40 = the thumb and index finger standing erect and close together

50 = the thumb bent at both joints and held against the palm

60 = the index finger closed over the thumb

70 = the first joint of the index finger resting over the first joint of the thumb, which is held nearly straight

80 = the tip of the index finger resting on the first joint of the thumb

90 = the thumb bent over the first joint of the index finger

The signs for 100, 200, 300, and so on are the same as 10, 20, 30, but made by the right hand; and the signs for 1,000, 2,000, 3,000 and so on are the same as 1, 2, 3 but made by the right hand. “To add two numbers, one simply signed the first, then made the mental arithmetical calculation and reproduced the gesture corresponding with the correct sum,” writes Angus Trumble in The Finger: A Handbook (2010). “The process was cumulative; to add a further number to the sum of the first two, you proceeded to represent the gesture corresponding with the new total, and so on. Likewise, the task of subtraction merely threw the whole system into reverse. It was perfectly clear to anyone observing you carry out these separate procedures whether the job in hand was one of addition or subtraction.”

Trumble says that at the end of the 19th century Wallachian peasants were discovered to have preserved a few methods of digital multiplication and division that had been preserved throughout the Roman empire. Here’s one.