Growing Room

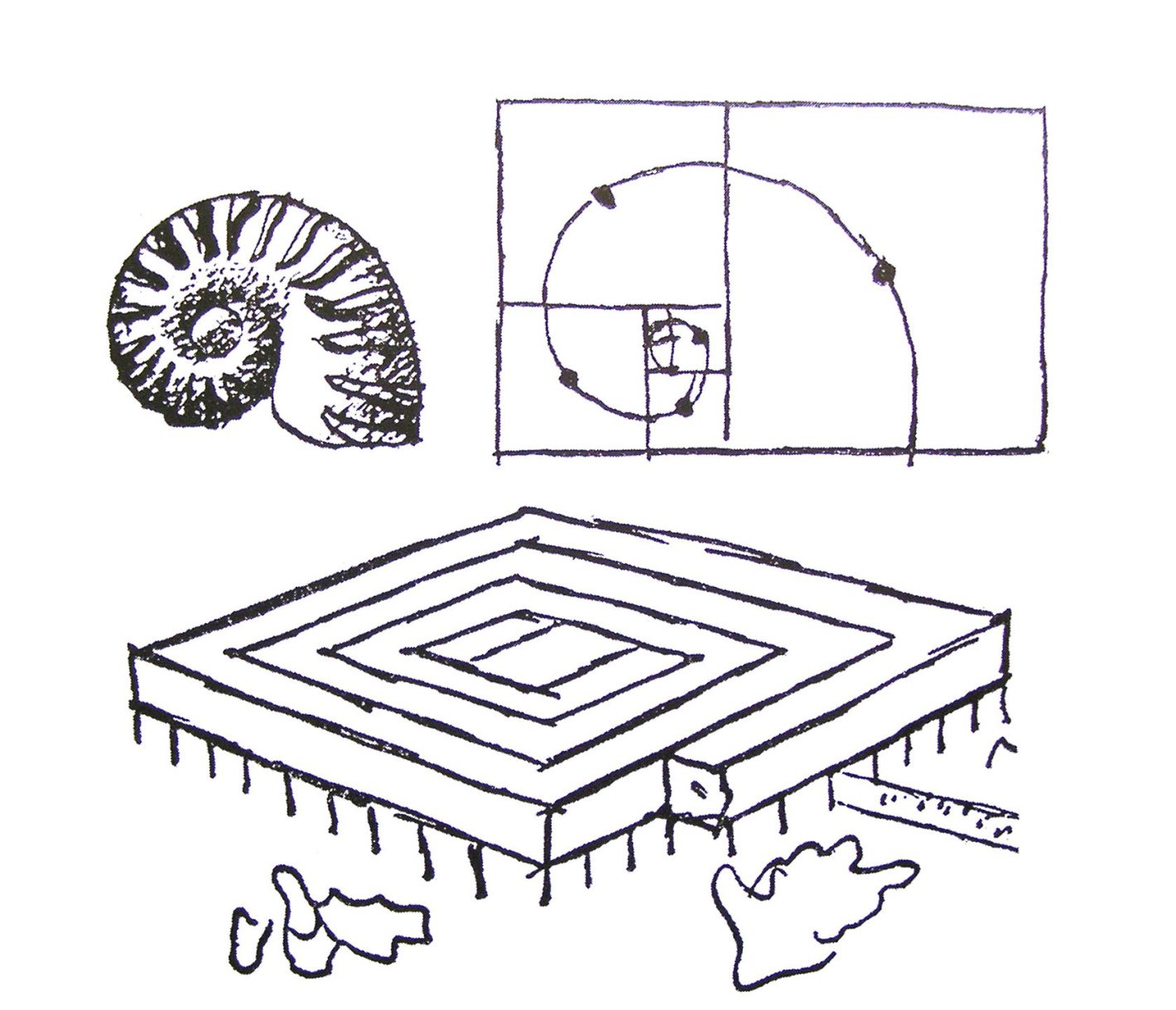

How can an art gallery accommodate a growing collection? In 1931 Le Corbusier proposed a Musée à croissance illimitée that would grow like a snail’s shell, coiling in a rectangular spiral as needs required and as funds became available.

“The means of orienting one’s self in the museum is provided by the rooms at half-height which form a ‘swastika,'” he explained. “Every time a visitor, in the course of his wanderings, finds himself under a lowered ceiling he will see, on one side, an exit to the garden, and on the opposite side, the way to the central hall. The Museum can be developed to a considerable length without the square spiral becoming a labyrinth.”

He presented the idea as a museum for Philippeville in North Africa in 1939, in a town planning project for Saint-Dié in 1945, and in a competition design to reconstruct the center of Berlin in 1958, but it was never realized.

(From Ulrich Conrads and Hans G. Sperlich, The Architecture of Fantasy, 1962.)

Multimedia

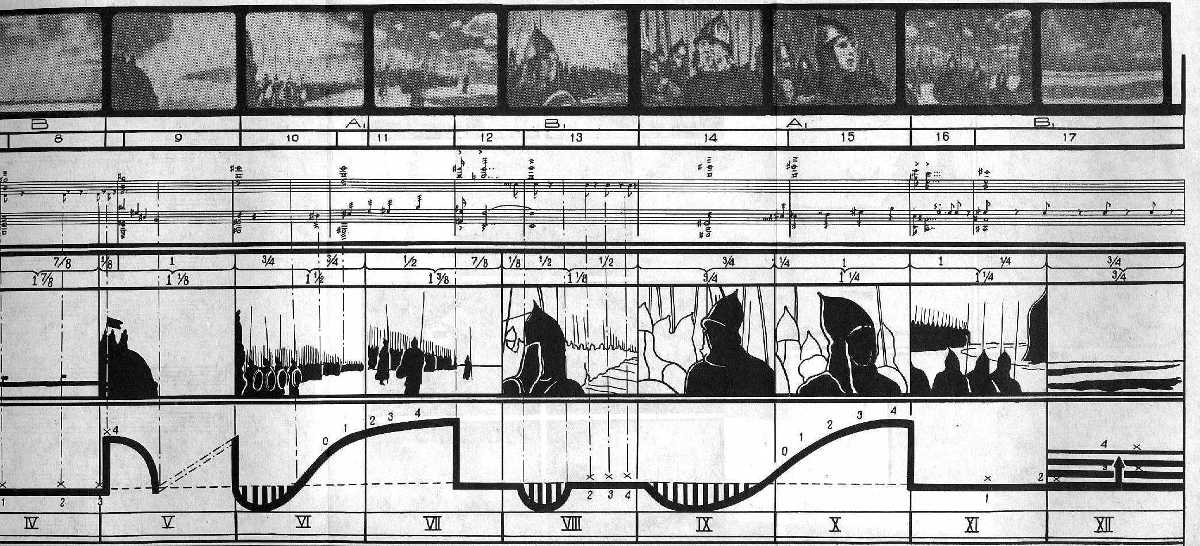

For his 1938 film Alexander Nevsky, Sergei Eisenstein worked so closely with composer Sergei Prokofiev that individual shots in the climactic “battle on the ice” were timed to correspond to the length of musical phrases.

Their collaboration during editing to marry music and imagery set the modern standard for filmmakers; Valery Gergiev, principal conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra, called Prokofiev’s score “the best ever composed for the cinema.”

Unquote

“The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.” — Orson Welles

Podcast Episode 248: Smoky the War Dog

In 1944, an American soldier discovered a Yorkshire terrier in an abandoned foxhole in New Guinea. Adopted by an Army photographer, she embarked on a series of colorful adventures that won the hearts of the humans around her. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll tell the story of Smoky the dog, one of the most endearing characters of World War II.

We’ll also contemplate chicken spectacles and puzzle over a gratified diner.

Red and Blue

A problem from the 1996-1997 Estonian Mathematical Olympiad:

A square tabletop measures 3n × 3n. Each unit square is either red or blue. Each red square that doesn’t lie at the edge of the table has exactly five blue squares among its eight neighbors. Each blue square that doesn’t lie at the edge of the table has exactly four red squares among its eight neighbors. How many squares of each color make up the tabletop?

“Oscar’s Morning Work”

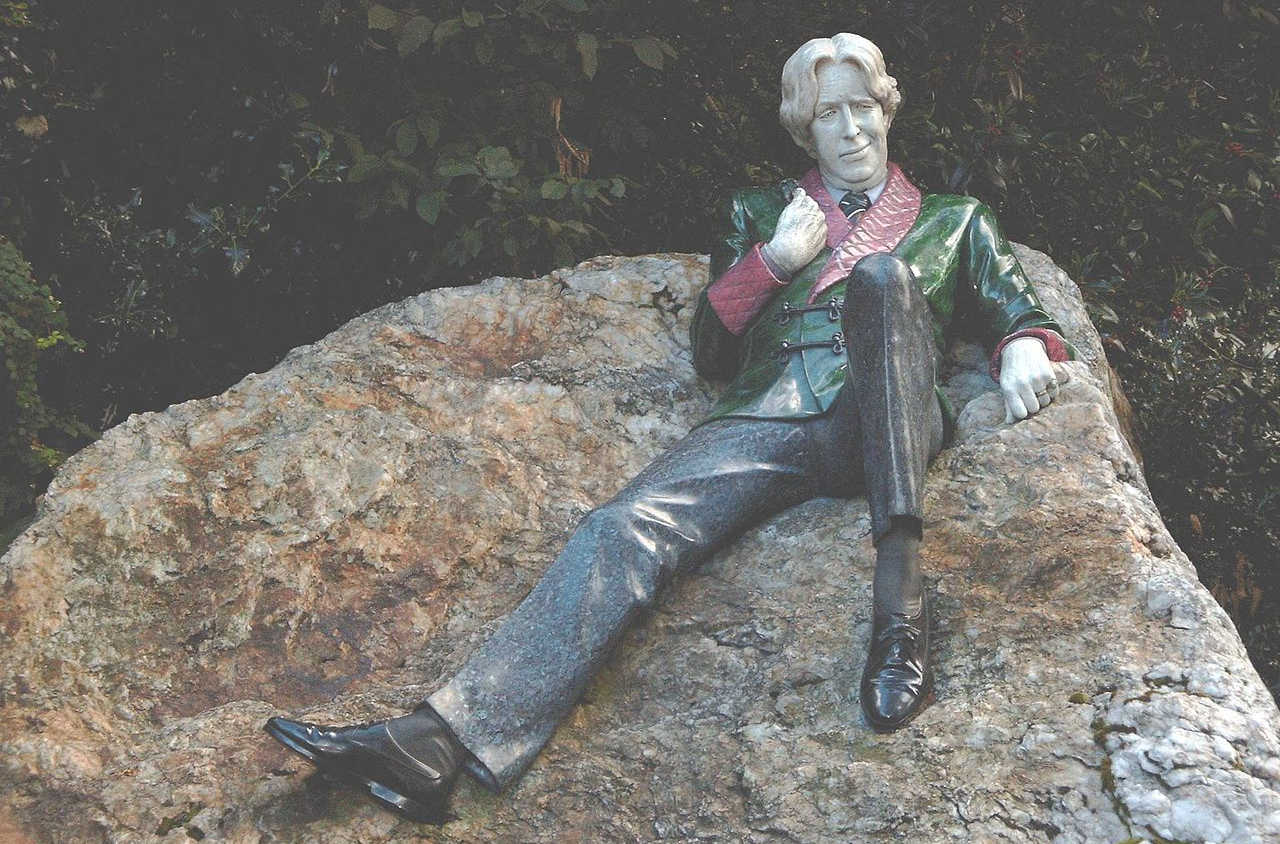

Oscar Wilde, among his various stories told here of which he was always the aesthetic hero, related that once while on a visit to an English country house he was much annoyed by the pronounced Philistinism of a certain fellow guest, who loudly stated that all artistic employment was a melancholy waste of time.

‘Well, Mr. Wilde,’ said Oscar’s bugbear one day at lunch, ‘and pray how have you been passing your morning?’ ‘Oh! I have been immensely busy,’ said Oscar with great gravity. ‘I have spent my whole time over the proof sheets of my book of poems.’ The Philistine with a growl inquired the result of that.

‘Well, it was very important,’ said Oscar. ‘I took out a comma.’ ‘Indeed,’ returned the enemy of literature, ‘is that all you did?’ Oscar, with a sweet smile, said, ‘By no means; on mature reflection I put back the comma.’ This was too much for the Philistine, who took the next train to London.

— Syracuse [N.Y.] Standard, May 21, 1884

More Madan

Excerpts from the notebooks of English belletrist Geoffrey Madan (1895-1947):

[Eton] masters asleep during Essay in various abandoned attitudes. Hornby like a frozen mammoth in a cave; Stone drooping; Vaughan like a monarch taking his rest; Churchill like a fowl on a perch with a film over his eyes.

A.E. Housman’s epitaph: the only member of the middle classes who never called himself a gentleman.

“It is the cause”: theory that Othello closes and lays down a Bible.

Gladstone’s Virgil quotations, like plovers’ nests: impossible to see till you’ve been shown.

“Love gratified is love satisfied, and love satisfied is indifference begun.” — Richardson

“It matters not at all in what way I lay this poker on the floor. But if Bonaparte should say it must be placed in this direction, we must instantly insist upon its being laid in some other one.” — Nelson

“Conservative: a man with an inborn conviction that he is right, without being able to prove it.” — Revd. T. James, 1844

“Lord Normanby, in recklessly opening the Irish gaols, has exchanged the customary attributes of Mercy and Justice: he has made Mercy blind, and Justice weeping.” — Lord Wellesley

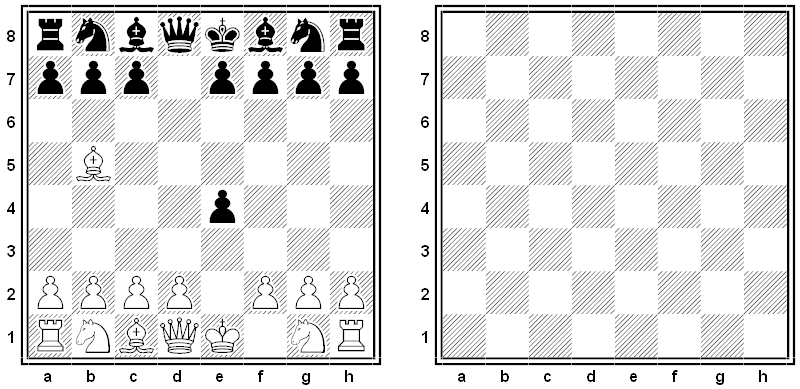

Alice Chess

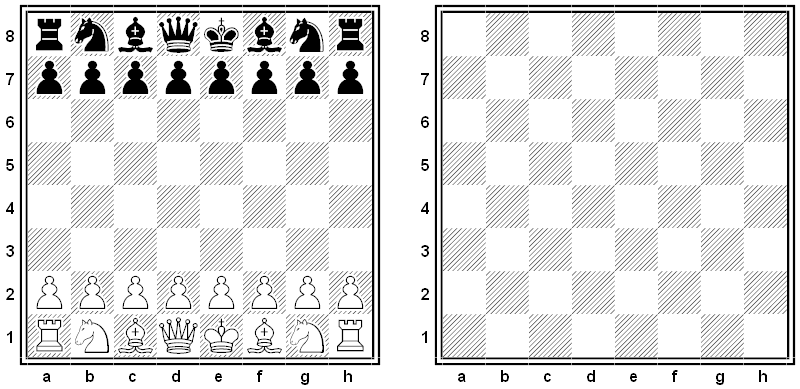

English chess enthusiast V.R. Parton invented this variant in 1953. The game is played on two boards, starting with the normal opening position on one board and a second board empty. The trick is that a piece that completes its move on one board “vanishes strangely off its board to appear suddenly on the other board, magically out of thin air!”

There are two stipulations: A move must be legal on the board on which it’s played, and the square to which the piece is transferred on the opposite board must be vacant. (This means that a piece can make a capture only on the board on which it stands.)

This makes things very confusing. Here’s a simple three-move game. White plays 1. e4, which means that his king pawn advances from e2, passes “through the looking glass,” and arrives at e4 on the second board. Black responds with 1. … d5, so his queen pawn arrives at d5 on the second board. White plays 2. Be2, meaning that his king’s bishop is transferred to e2 on the second board. And now Black makes the mistake of playing 2. … dxe4 — his pawn on d5 on the second board captures the white pawn there, which means the white pawn is removed from play and the black pawn finds itself on e4 on the first board. That’s a mistake, because White can play 3. Bb5:

The white bishop returns to the first board, checking the black king. Strangely, this is checkmate: Black can’t capture the attacking piece or move out of danger, and he can’t interpose a piece — any piece that he moves on the first board will find itself on the second, and there are no pieces on the second board that could move to c6 or d7.

Parton wrote, “One board being as a looking-glass to the other, the resulting play is a game which has a character as fantastic perhaps as Alice’s own game in Through the Looking-Glass.”

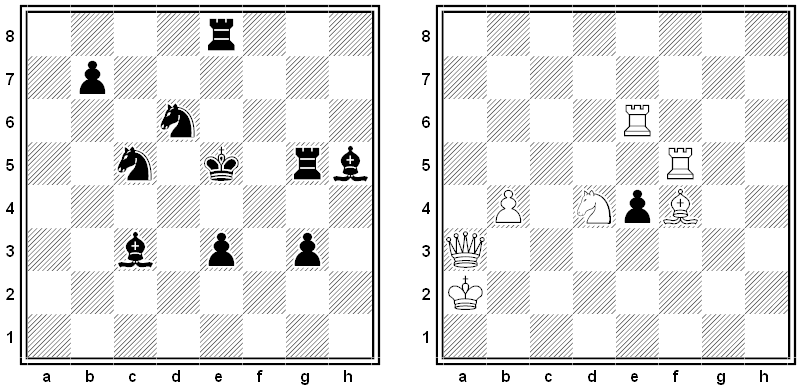

Here’s an Alice chess problem by Udo Marks. How can White mate in two moves?

Constrained Writing

In Paul Griffiths’ 2008 novel let me tell you, Ophelia tells her story using only the 481-word vocabulary given to her in Hamlet:

So: now I come to speak. At last. I will tell you all I know. I was deceived to think I could not do this. I have the powers; I take them here. I have the right. I have the means. My words may be poor, but they will have to do.

What words do I have? Where do they come from? How is it that I speak?

There will be a time for me to think of these things, but right now I have to tell you all that I may of me — of me from when I lay on my father’s knees and held up my hand, touching his face, which he had bended down over me. That look in his eyes. …

“Where other characters from the play speak, they are similarly confined to the words Shakespeare gave them. Gertrude, for example, can use only Ophelian words present also in her own language. The one exception is the prefatory statement, whose author has full access to his play vocabulary.” A longer excerpt is here.